Managing Anaphylaxis in the Emergency Department Contents

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Emergency Medicine Guidelines |

| Book: | Managing Anaphylaxis in the Emergency Department Contents |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 10:25 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 Oct 2024"

- Committee

Members of the Guideline Development Group (GDG) of This

Guideline:

Adel Hamed Elbaih, Emergency Medicine Department, Faculty

of Medicine, Suez Canal University

Amany Abuzeid, Emergency Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University

Diaa Abdelmawla Salama, Emergency Medicine, Cairo

Hatem Mohamed Shohdy, Emergency Medicine, Menoufia.

Khaled Shelbaya, Research Department, Alnas Hospital, NGO Al-Qalyubia

Sally Wassfy, Emergency Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University

Monira Taha, Emergency Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University

Jehan Elkholy, Emergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University

➡️The Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all members of Emergency Medicine Guidelines Committee.

- Abbreviations

|

AGREE II |

Appraisal of Guidelines For Research & Evaluation |

|

ED |

Emergency department |

|

EKB |

Egyptian Knowledge Bank |

|

EtD |

Evidence to decision |

|

GDG |

Guideline Development Group |

|

GRADE |

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

|

IM |

Intramuscular |

|

IV |

Intra-Venous |

|

RCUK |

Resuscitation Council United Kingdom |

- Glossary

|

Anaphylaxis |

A serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction that is usually rapid in onset and may cause death. Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by potentially life-threatening compromise in airway, breathing and/or the circulation, and may occur without typical skin features or circulatory shock being present. |

|

Antihistamine drugs |

Class of drugs that blocks the action of histamines, for symptomatic relief of associated manifestations such as fever, skin rash, itching, sneezing, a runny nose, and watery eyes. |

|

Bronchia Asthma |

A chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by bronchial hyperreactivity and a variable degree of airway obstruction. It is diagnosed on the basis of the clinical history, physical examination, and pulmonary function tests, including reversibility testing and measurement of bronchial reactivity. |

|

Corticosteroids drugs |

Corticosteroids are synthetic analogues of the natural steroid hormones produced by the adrenal cortex, specifically glucocorticoids, which act by binding to intracellular receptors. Upon activation, it inhibits gene expression and translation in inflammatory leukocytes and structural cells, such as epithelium. |

- Executive Summary

This guideline is the key for the initial management of anaphylaxis (a life-threatening condition compromising the airway, breathing, and/or circulation) in the emergency department (ED), to be used by emergency physicians and any physician who works in the ED, whatever the specialty. It has been made in a simple concise way to go through in a quick stepping manner giving the clues to most critical points of such a critical condition in the ED.

The guideline was developed through adoption and adaptation methodology by a consensus of expert field group, Guideline Development Group (GDG) of the Egyptian National Clinical Guidelines Centre, supporting the 2021 update of the Resuscitation Council United Kingdom (RCUK). Because of lacking randomized clinical trials, the certainty of evidence for these recommendations was moderate or less.

We recommend Strength 1- giving

adrenaline as the first line of treatment Strong 2- early

administration of adrenaline once symptoms of anaphylaxis are recognized or

suspected Weak 3- giving

adrenaline by intramuscular route as the initial treatment of anaphylaxis Strong 4- following the

list of adrenaline doses according to age Strong 5- repeating

intramuscular adrenaline every 5-15 min in cases of refractory anaphylaxis Weak 6- iv bolus of

crystalloid in case of hemodynamic instability and in refractory anaphylaxis Weak 7- against using

antihistamines as initial treatment of anaphylaxis Weak 8- against using

corticosteroids in initial treatment of anaphylaxis Weak 9 - giving

inhalational beta2 agonist as part of treatment in the presence of wheezy

chest Weak 10- a minimum of

6 hours of observation after resolution of symptoms for all patients with a

confirmed diagnosis. Weak

- Introduction

Anaphylaxis is an acute, life-threatening systemic hypersensitivity reaction that compromises the airway, respiration, and/or circulation. It may occur without typical skin features, circulatory shock, or compromised breathing being present 1. Anaphylaxis should be recognized and treated immediately 2. Emergency department (ED) anaphylaxis care involves proper triage, administration of adrenaline, and the general management of airway, breathing, and circulation 3. Therefore, guidelines for managing anaphylaxis in the ED must be based on the best available research evidence, theory, and expert consensus.

This evidence review was undertaken by the Anaphylaxis Guideline Development Group (GDG) of the Egyptian National Clinical Guidelines Centre, supporting the 2021 update of the Resuscitation Council United Kingdom (RCUK). The GDG used an internationally accepted approach for adoption, adaptation, and de novo guideline development based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) evidence to decision (EtD) framework, referred to as GRADE-ADOLOPMENT 4. The EtD framework facilitates the use of evidence in a structured and transparent way to inform decisions in the context of clinical and public health recommendations and decisions 5.

➡️Purpose

To our knowledge, few registries of anaphylaxis exist in Egypt, and no specific Egyptian guidelines are available. Therefore, we aimed to design Egyptian guidelines to prevent treatment errors in the ED among Egyptians. This guideline may also benefit institutions worldwide, particularly in low-middle-income countries.

Intramuscular (IM) adrenaline is considered the first-line drug for the treatment of anaphylaxis 6, but there is considerable divergence between published guidelines regarding the role of adrenaline in comparison to other available medications 7. This may be due to a lack of high-certainty evidence to support treatment recommendations 8. However, based on prior publications and the experience of experts, this guideline selects and answers key questions that are key to multidisciplinary healthcare providers in the ED. Adherence to this guideline should improve the care of anaphylaxis patients at Egyptian medical institutions.

➡️Scope and Target Audience

This document's recommendations are directed to emergency physicians and other specialists working in the ED of Egyptian hospitals in the different sectors of the Egyptian healthcare system. The key research questions were identified from the previous RCUK guidelines. The EtD framework for each question/topic was discussed by the expert in emergency medicine to adapt those recommendations in the Egyptian ED setting (see Annex 1).

- Methods

Multiple sources provided by the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB) platform were used to identify up-to-date international guidelines. We searched for guidelines covering ED management of anaphylaxis. We included international guidelines regardless of whether they used the GRADE EtD framework (and some guidelines preceded the EtD methodology) or not.

After applying the Appraisal of Guidelines For Research & Evaluation (AGREE II) tool 9, we chose two initial guidelines: one developed by medical Chinese societies 10and the other by the RCUK 11. We decided to choose the RCUK guideline because it was more suitable for applying the GRADE ADOLOPMENT process.

Each committee member chose one or two recommendations and searched for any key studies related to those recommendations published after the date of the RCUK guideline publication. The studies that could potentially influence the recommendation strength or the level of certainty of evidence were shared among the working group.

The GRADE-PRO web-based application was used to create the draft of the evidence-to-decision (EtD) tables and to facilitate the committee members’ voting for each recommendation 12. The template provided by RCUK guidelines was used to guide the discussion. The EtD tables were then reviewed by the GDG, and a consensus was reached on whether to support the previous recommendation (“adopted”) or indicate a need to update the recommendation (“adapted”). If there was no consensus regarding the strength of the recommendation, the GDG chair led a thorough discussion to achieve a final agreement. The strength for each recommendation was assigned as either strong or weak (see Annex 1).6

➡️Summary of the Evidence

The certainty of evidence for each recommendation was determined as High, Moderate, Low, or Very Low (Table 1), according to the available evidence in RCUK guidelines in addition to the updated literature review conducted by the committee members.

Table 1 – Certainty of evidence 4

|

Certainty of evidence |

Explanation |

|

High |

We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect |

|

Moderate |

We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

|

Low |

Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

|

Very low |

We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

➡️Contextual Factors Considerations

Although evidence regarding the performance, efficacy, and safety of interventions is crucial for all guidelines, it's important to consider contextual factors of the EtD framework when formulating recommendations. These considerations include the feasibility and acceptability of an intervention in each setting, its cost-effectiveness, and the potential impact on reducing or increasing inequities. Patients' values and preferences should also be considered. All these contextual factors were discussed by the GDG, considering the Egyptian context.

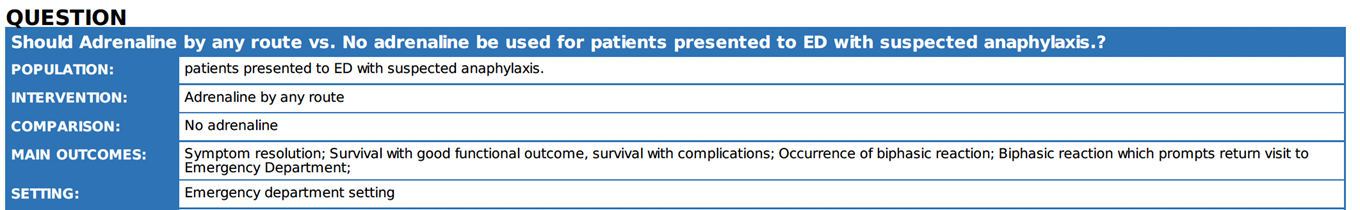

- Recommendations

GDG adapted 10 recommendations. Five of them relate to adrenaline as a first line for anaphylaxis treatments, adrenaline timing, dosage, method of administration, and subsequent usage in refractory cases. The other 5 recommendations focused on the role of potential adjuvant therapies (i.e., intravenous fluid, antihistamine, corticosteroids, and beta2 agonist) in addition to patients' disposition from ED. The guideline recommends against using antihistamines and corticosteroids as part of the initial therapy.

The intravenous (IV) route is not recommended for initial management of anaphylaxis, except by senior physicians who hold the privilege of using IV adrenaline. Also, the privilege of using IV adrenaline infusion to treat refractory anaphylaxis should be available for the treating physician. Although GDG advised against using antihistamines or corticosteroids as part of the initial anaphylaxis treatment, antihistamines could be used to manage skin manifestations, and corticosteroids could be given with IV crystalloids in case of hemodynamic instability and in refractory anaphylaxis, provided that their administration is not delaying adrenaline administration.

The GDG does not recommend fast-track discharge (after 2 h of observation from the resolution of anaphylaxis). Most of the Egyptian patients do not have access to adrenaline auto-injectors to be safely discharged on them. Also, adequate supervision following discharge is not guaranteed. Also, we are not sure about adequate medical supervision following discharge. Key research questions, recommendations, a summary of the evidence, and remarks related to the implementation are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2, Key research questions, recommendations, a summary of the evidence, and remarks related to the implementation

|

|

The question |

The recommendation |

Summary of evidence |

Remarks |

|

1. |

Is adrenaline effective for the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We recommend adrenaline as the first line

treatment for anaphylaxis in ED |

There is little doubt that sufficient levels of adrenaline lead to the resolution of symptoms, while delayed administration can lead to prolonged reactions, hypotension, and fatal outcomes 13 14. |

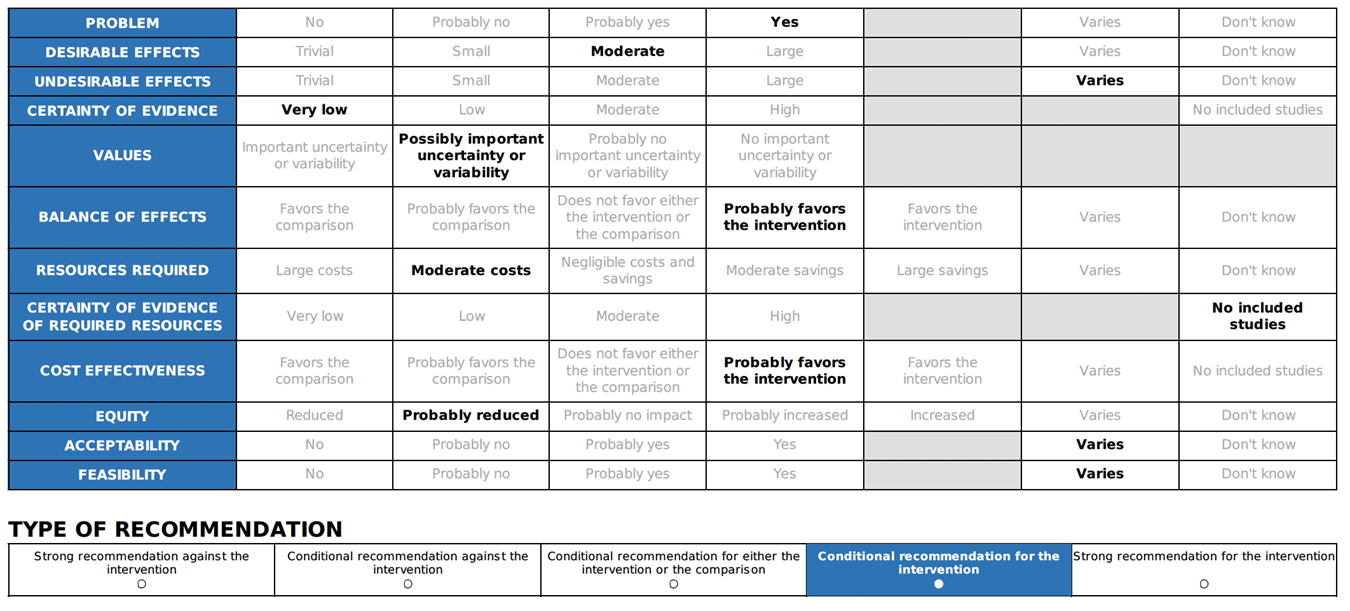

A clear definition of anaphylaxis should be provided and demonstrated through the ABCDE approach (see Annex 2,3), to discriminate it from allergic skin reaction which is not an emergency. |

|

2. |

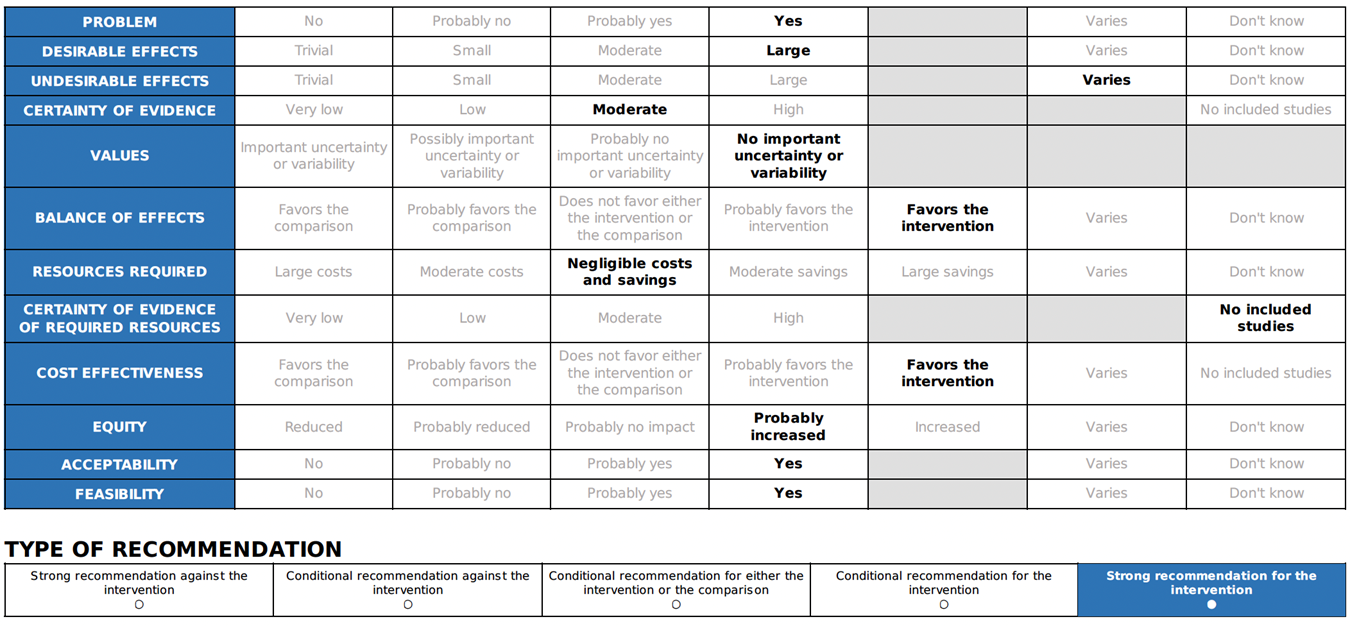

What is the optimal timing of adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We recommend that adrenaline should be

administered early once symptoms of anaphylaxis have been recognized or

suspected |

Although there is a lack of high-certainty evidence to differentiate the effect of early versus delayed administration of adrenaline on clinical outcomes, it is reasonable to recommend administering adrenaline as soon as symptoms of anaphylaxis appear 7 13.

|

It seems reasonable to ensure the availability of adrenaline in ED to be given as soon as features of anaphylaxis are apparent. |

|

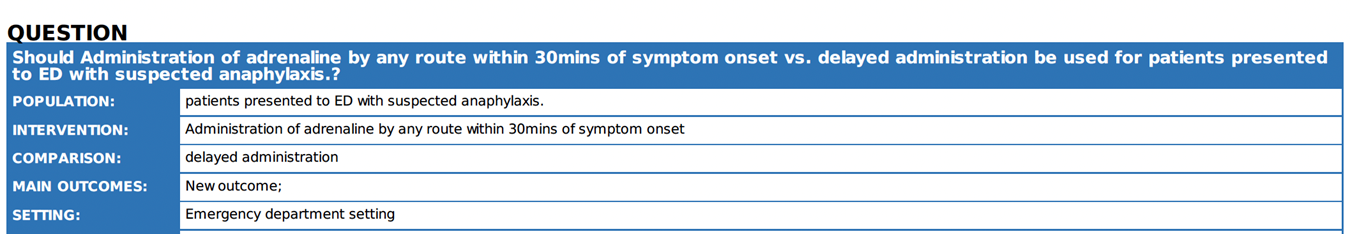

3. |

What is the optimal route of adrenaline to treat anaphylaxis? |

The intramuscular (IM) route is recommended

for initial adrenaline treatment for anaphylaxis |

There are currently no trials comparing the effectiveness of different ways of administering adrenaline to patients during anaphylaxis. The use of IM adrenaline as the initial treatment for anaphylaxis due to its favourable safety profile, especially for patients with cardiovascular issues 15. |

The IV route is not recommended for initial management of anaphylaxis, except by those skilled and experienced in its use.

|

|

4. |

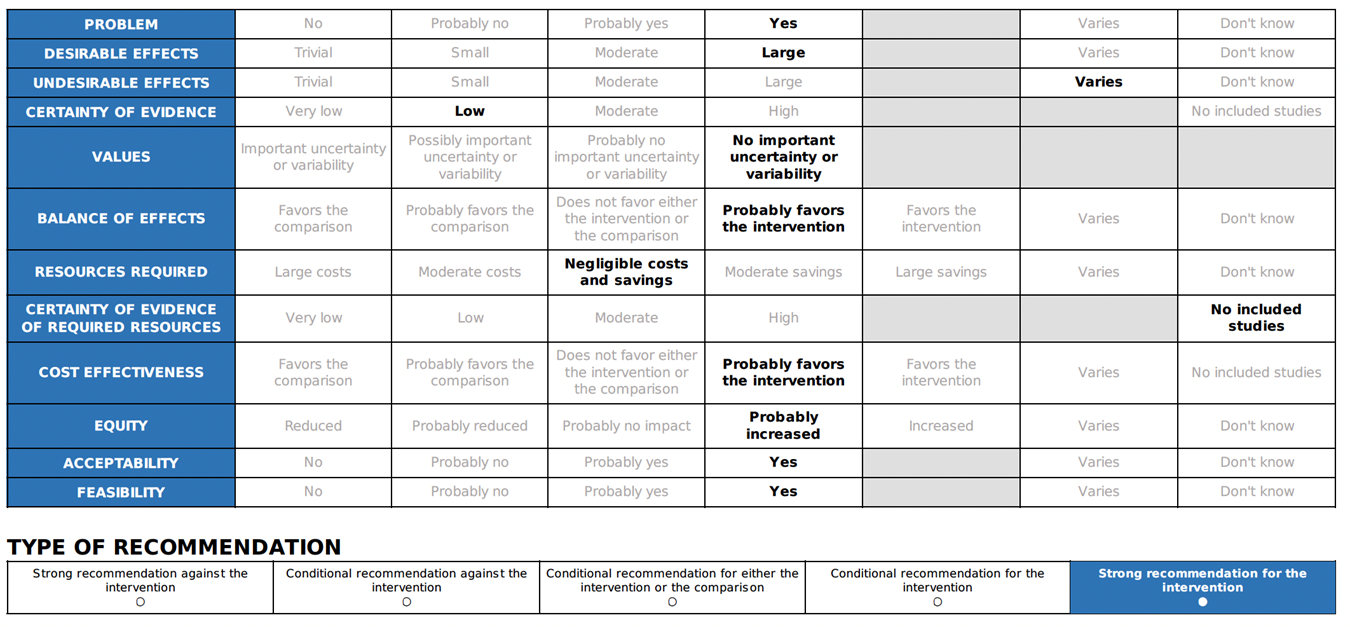

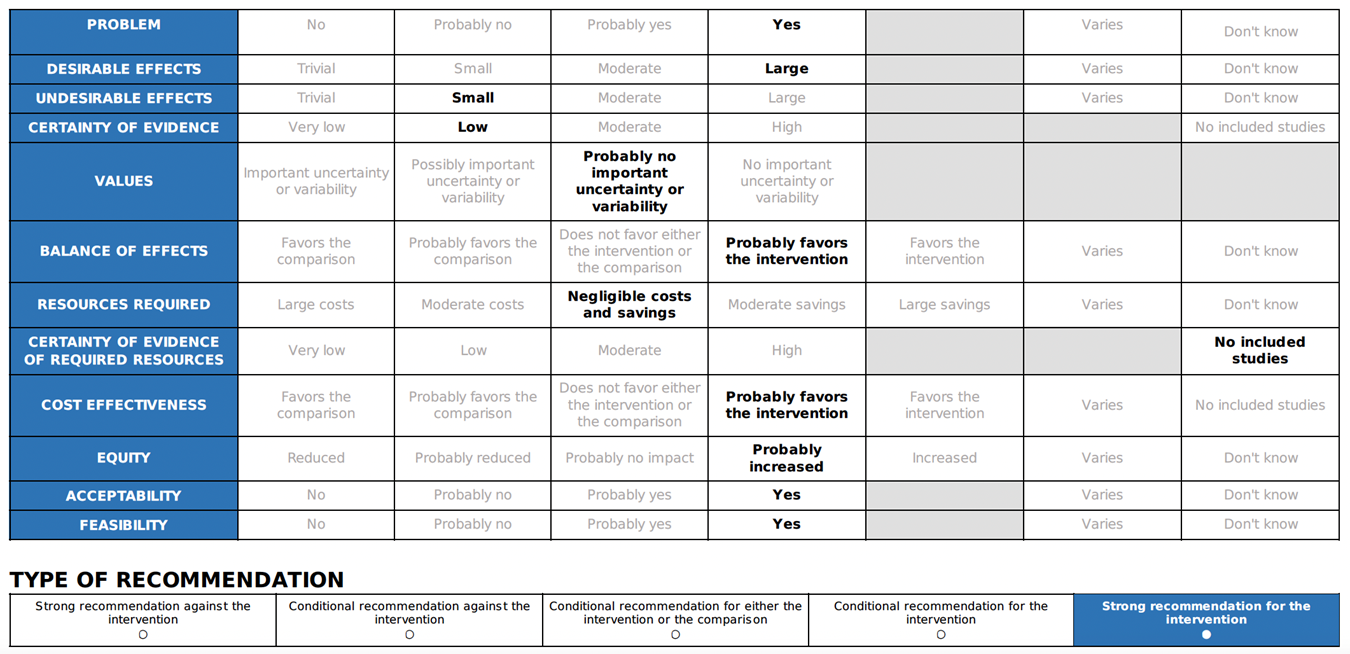

What is the optimal dose of intramuscular adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We recommend IM adrenaline dosage listed according to age (strong recommendation, low certainty evidence)

|

The dosing regimen listed has been proven safe and effective in clinical practice for over 20 years. International guidelines recommend a dose of 0.01 mg/kg (maximum 500 micrograms) for children, which should be titrated to achieve a clinical response. Several guidelines also recommend simplifying the dosing schedule based on age categories, making it safer and more practical for emergency use by simplifying the preparation and injection process 1 16 17.

. |

Table with doses and equivalent ml should be available in ED. Adults: 500 ug (0.5 mg) IM (0.5 mL of 1 mg/ml [1:1000]) Children >12 years: Children 6-12 years: Children 6 months-6 years: 150 micrograms IM (0.15ml) Children <6 months: 100-150 micrograms IM (0.1 0.15 mL) |

|

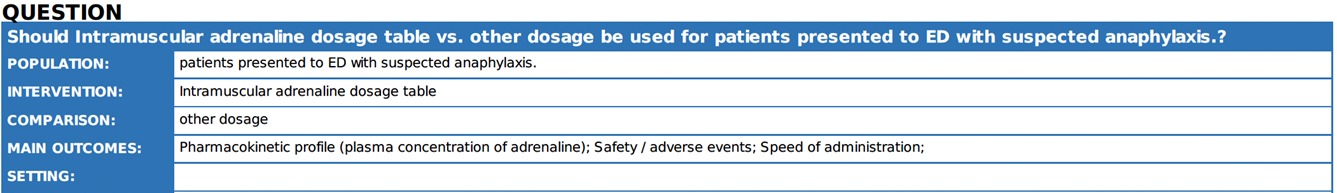

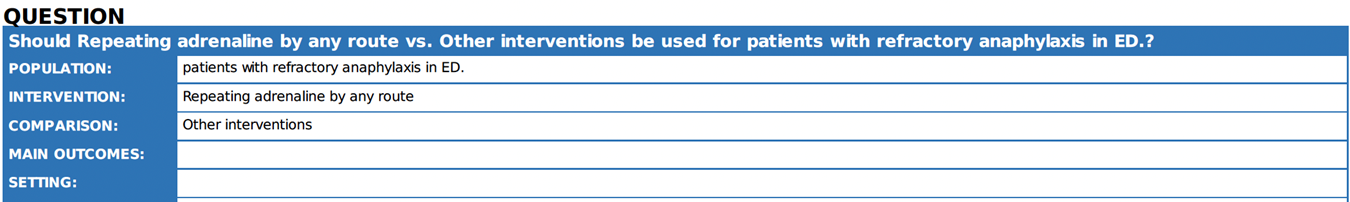

5. |

Is adrenaline effective in the treatment of anaphylaxis reactions refractory to initial treatment with adrenaline? |

We recommend that: 2- Low dose intravenous (IV) adrenaline infusions appear to be effective and safe to treat refractory anaphylaxis.

very low certainty evidence). |

The absorption of adrenaline following intramuscular injection follows a biphasic profile, with the initial peak occurring within 5-10 minutes 18. Therefore, IM adrenaline should be repeated every 5-15 min where features of anaphylaxis persist 15. The rationale for waiting longer than 5 min when symptoms have failed to respond to adrenaline is unclear. Low-dose adrenaline infusions are effective in case series of human anaphylaxis 19 20 and are included as the treatment of choice for refractory anaphylaxis in national guidelines in Australia for the acute management of anaphylaxis; 2024 21. |

Where respiratory and/or cardiovascular features of anaphylaxis persist despite 2 appropriate doses of adrenaline (administered by IM or IV route), urgent expert help (e.g. from experienced critical care clinicians) should be sleeked to establish an intravenous adrenaline infusion to treat refractory anaphylaxis. Complications due to adrenaline occur regardless of route but are more common after IV administration. |

|

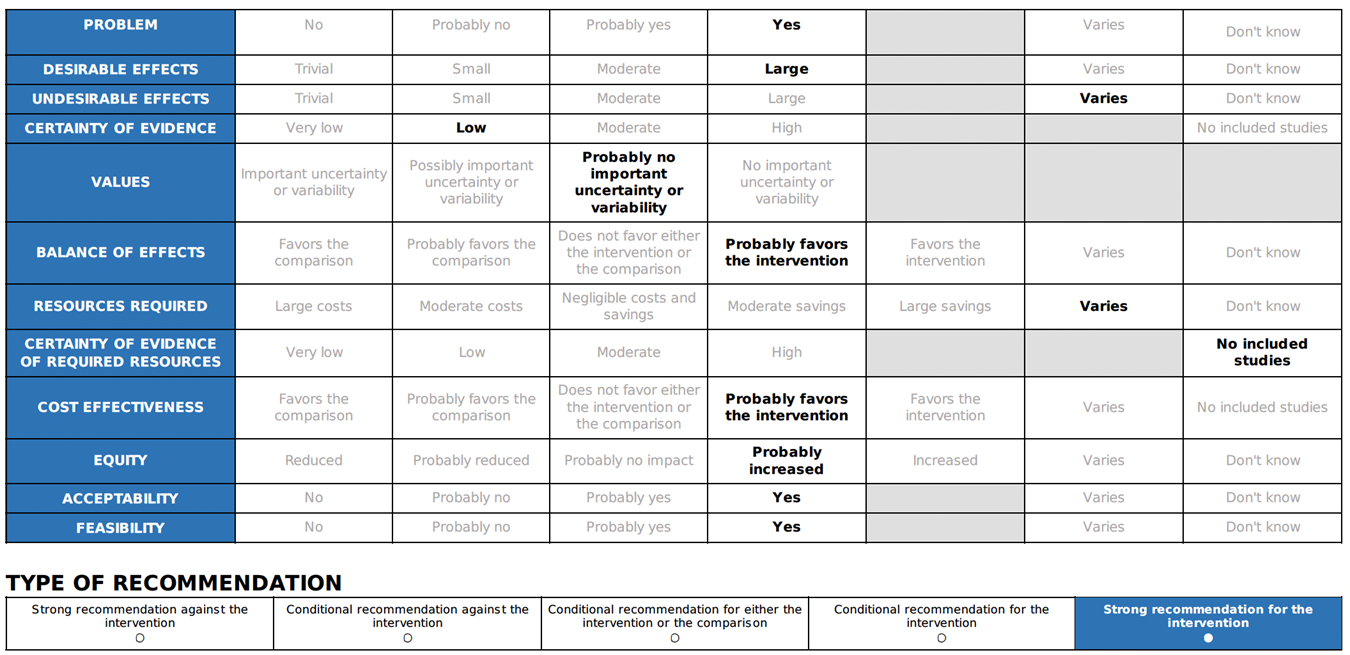

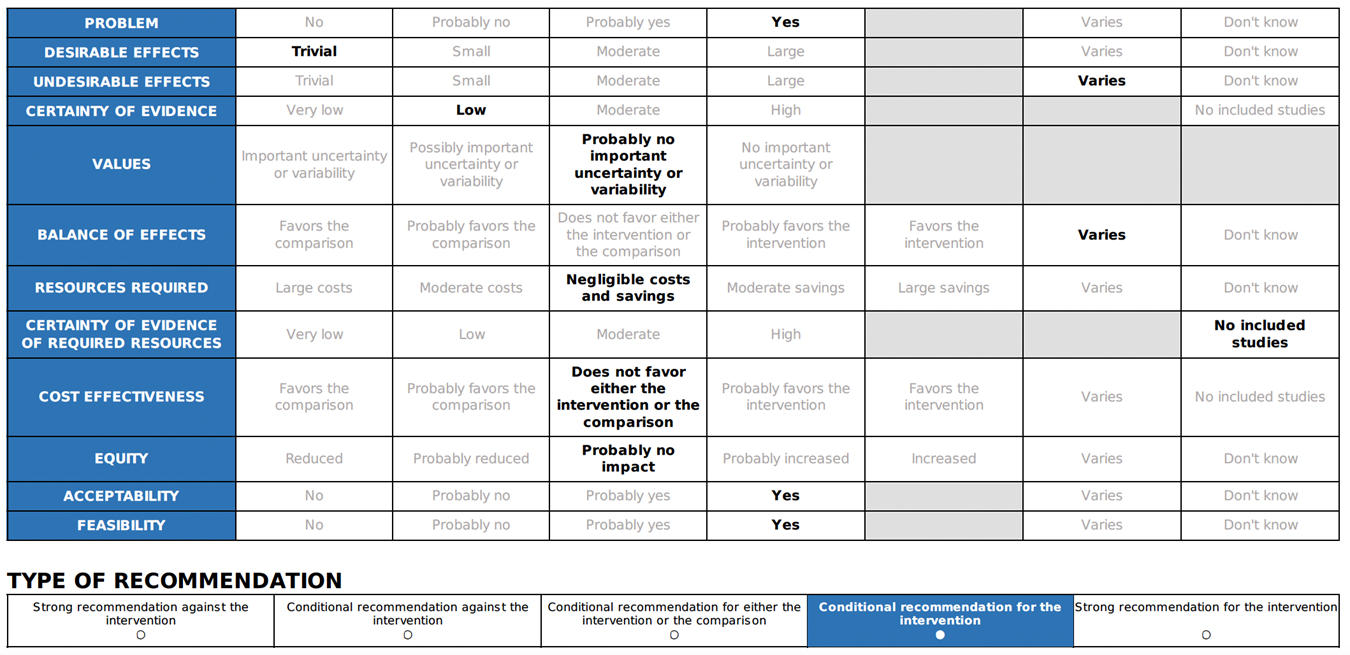

6. |

Are intravenous fluids effective as an adjuvant treatment for anaphylaxis? |

In case of anaphylaxis with haemodynamic

instability, IV crystalloid fluids should be given. |

Crystalloid infusion was more effective in restoring venous return when compared to a single dose of IM adrenaline 22. |

IV access should be obtained as early as possible, as a single bolus of IV crystalloid can be used in refractory anaphylaxis. |

|

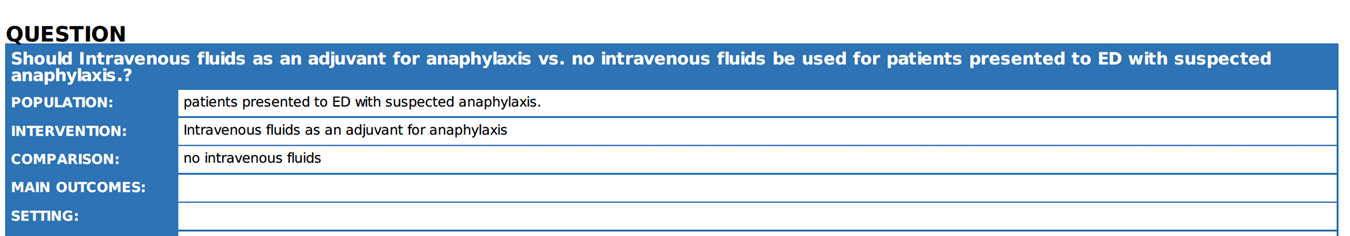

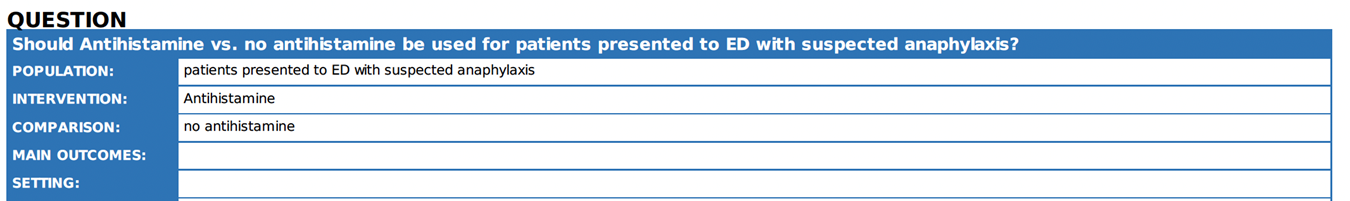

7. |

Are antihistamines effective in the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We advise against using antihistamines as

part of the initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis. |

Antihistamines are not to be utilized in the treatment of respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms associated with anaphylaxis. Their application should not impede the timely administration of adrenaline and intravenous fluids required to address such symptoms 1 17 21. |

We suggest antihistamines are used to treat skin symptoms which often occur as part of allergic reactions without delaying timely and appropriate use of adrenaline to treat anaphylaxis |

|

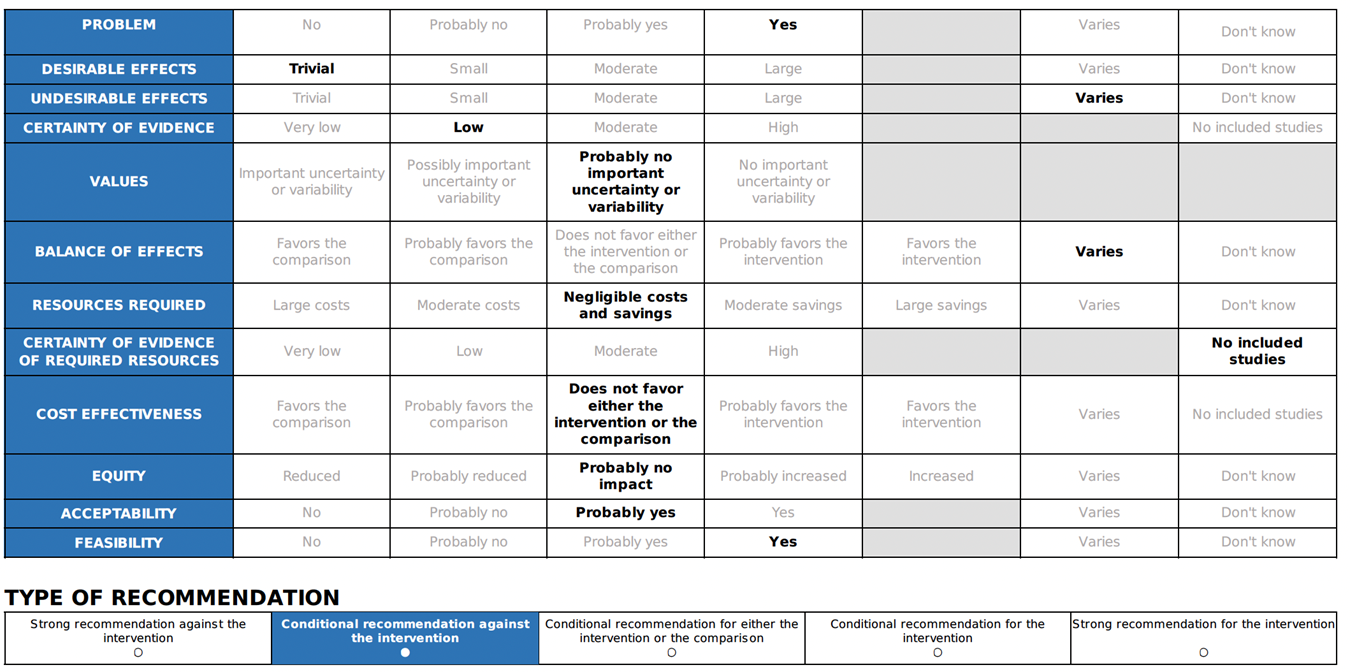

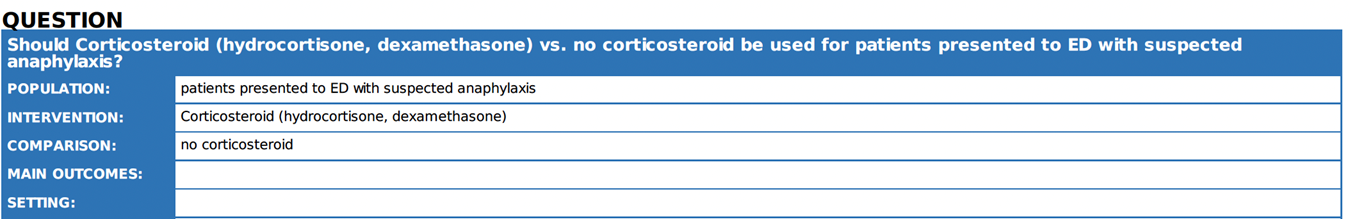

8. |

Are corticosteroids effective in the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We advise against using corticosteroids as

part of initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis |

Corticosteroids increased the admission rate in the intensive care units and Hospital in a Canadian Emergency Department Anaphylaxis Cohort 23. Also, corticosteroids may postpone the use of adrenaline which is life saving 24. |

Corticosteroids could be included in the management of refractory anaphylaxis and shock. |

|

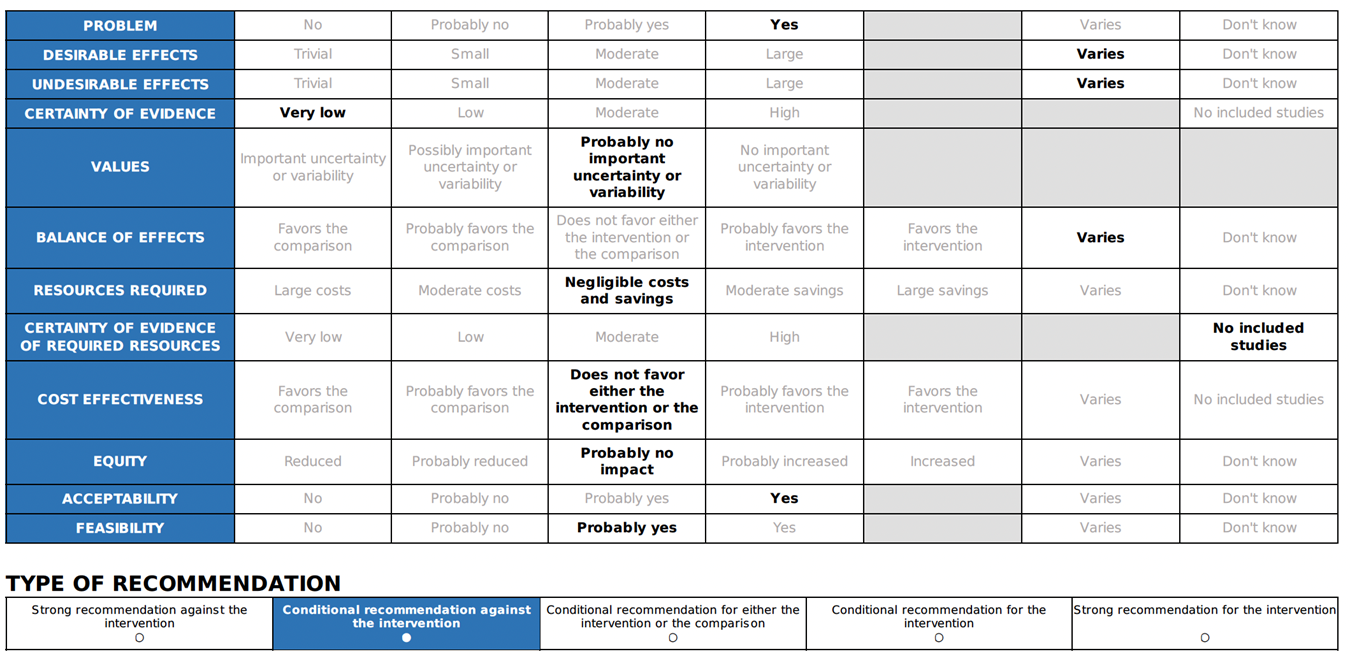

9. |

Are inhaled beta-2 agonists effective in the treatment of anaphylaxis? |

We suggest that inhaled beta2 agonist can only be used as an adjunct treatment

to adrenalin in the presence of wheezing for anaphylaxis

|

Short-acting beta-2 agonists (inhaled through a nebulizer or spacer) can be used to relieve lower respiratory symptoms and anaphylaxis, such as wheezing and coughing 25. But it should not be used instead of adrenaline as a first line of treatment for anaphylaxis 21. |

Considering bronchial asthma as an important differential diagnosis of acute onset dyspnea and wheezes.

|

|

10. |

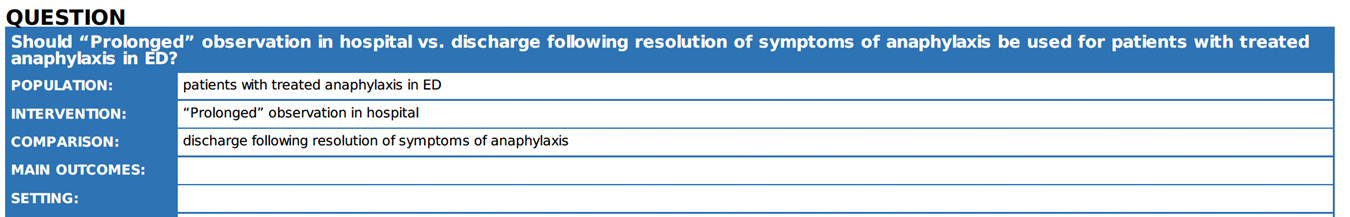

How long should patients be observed in hospital following anaphylaxis? |

We recommend, minimum 6 hours observation after resolution of symptoms for all patients. Observation for at least 12 hours after the symptoms have resolved should be ensured in the following cases: - A severe reaction that necessitated more than 2 doses of adrenaline. - Patients with severe asthma or those who experienced severe respiratory compromise during the reaction. - Possibility of continued absorption of allergen, such as with slow-release medications. - Patients who present late at night or may not be able to respond to any deterioration. - Patients in areas where access to

emergency care is difficult. |

The optimal duration of observation following anaphylaxis is unknown. We suggest using a risk-stratified approach for discharging patients after anaphylaxis 24 26 . |

The rapid discharge of patients within 2-6 hours after anaphylaxis symptoms have been resolved is not considered a safe approach. However, relatively early discharge of stable patients or arranging for safe transfer to another hospital should be considered in the event of limited capacity at busy ED and small hospitals during a medical crisis. |

➡️Research Gaps

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, multisystem hypersensitivity reaction that affects multiple systems. The distribution of anaphylaxis varies based on age, gender, race, geographical location, and socioeconomic status of the individuals involved; therefore, describing the epidemiology of anaphylaxis in developing countries is very crucial 27. The incidence of anaphylaxis is often underestimated in various studies due to difficulties in recognizing it and variations in diagnostic criteria among different studies and countries 28. Furthermore, the underestimation of anaphylaxis diagnosis is more pronounced in developing countries, and when diagnosed, proper management is sometimes lacking 29.

The overall prognosis for anaphylaxis is generally good. Injecting adrenaline early in the case of anaphylaxis (i.e., before arriving at the emergency department) can substantially reduce the chances of being admitted to the hospital. On the other hand, delayed administration of adrenaline has been linked to numerous cases of anaphylaxis-related fatalities in a large series of cases 30. The impact of the lack of auto-injectable devices that deliver adrenaline in the pre-hospital phase on anaphylaxis prognosis is not well studied. Cost-effectiveness analysis to study the impact of incorporating adrenaline auto- injectable adrenaline devices in the Egyptian Healthcare system should be conducted.

Guidelines for both adults and children stress the importance of prompt diagnosis for optimal treatment 31. Mistakes in diagnosing anaphylaxis can happen due to the limited time available for diagnosis, the stressful environment of the emergency room, incomplete clinical features in early anaphylaxis, and the lack of useful laboratory markers. Sensitive and specific biomarkers for anaphylaxis diagnosis will reduce its misdiagnosis 32.

A simplified universal anaphylaxis guideline dedicated to recognizing, diagnosing, and risk stratification of this condition is still unmet (see annex 3)33. Future implementation research is necessary to minimize discrepancies between guidelines and elucidate reasons for differences 34.

➡️ Monitoring and Evaluation

Clinical indicators for recommendations monitoring are needed to ensure achieving the impact of guidelines (Table 3).

Table 3: Clinical indicators for recommendations

|

Recommendation |

Clinical indicators |

|

Adrenaline as the first line treatment for anaphylaxis. |

100 % of patient presented with anaphylaxis shock should be treated with adrenaline. |

|

Adrenaline should be administered early once symptoms of anaphylaxis have been recognized or suspected. |

Percentage of experiencing anaphylaxis who are promptly treated with adrenaline. |

|

The IM route is recommended for initial adrenaline treatment. |

Percentage of patients treated with adrenaline in ED by appropriate route. |

|

IM adrenaline dosage listed according to age |

100 % of patients prescribed adrenaline in treatment anaphylaxis should be for the correct dose |

|

Subsequent doses of adrenaline, titrated to clinical response, in patients whose symptoms are refractory |

Percentage of patients with anaphylaxis who received adrenaline 2nd dose due to refractory reaction after initial dose of adrenaline |

|

IV crystalloid for treating anaphylaxis with haemodynamic instability |

Percentage of patients with anaphylaxis who received IV fluid (bolus and maintenance) |

|

Antihistamines shouldn’t be the initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis |

Percentage of patients with anaphylaxis who administrated antihistamines prior to adrenaline |

|

Corticosteroids shouldn’t be the initial emergency treatment for anaphylaxis |

Percentage of patients with anaphylaxis who administrated corticosteroids prior to adrenaline |

|

Inhaled beta2 agonist as an adjunct treatment to adrenaline in the presence of wheezing for anaphylaxis |

Percentage of patients with lower respiratory symptoms in the context of anaphylaxis inhaled beta-2 agonists |

|

Minimum 6- 12 hours observation after resolution of symptoms of anaphylaxis according to the associated risk |

Percentage of patients with an acute

episode of anaphylaxis are observed in hospital for duration less than 6

hours. |

➡️Update to guidelines

The guidelines will be continuously updated based on

new and relevant evidence.- References

1. Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M, et al. World allergy organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13(10):100472. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100472 [published Online First: 20201030]

2. Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: Summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2006;117(2):391-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1303

3. McHugh K, Repanshek Z. Anaphylaxis: Emergency Department Treatment. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 2022;40(1):19-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2021.08.004

4. Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;81:101-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009

5. Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 2016:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016

6. Simons FER, Ardusso LRF, Bilò MB, et al. International consensus on (ICON) anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organization Journal 2014;7(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-7-9

7. McLure M, Eastwood K, Parr M, et al. A rapid review of advanced life support guidelines for cardiac arrest associated with anaphylaxis. Resuscitation 2021;159:137-49. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.001 [published Online First: 20201014]

8. Soar J, Pumphrey R, Cant A, et al. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions--guidelines for healthcare providers. Resuscitation 2008;77(2):157-69. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.02.001 [published Online First: 20080320]

9. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2010;182(18):E839-E42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449

10. Li X, Ma Q, Yin J, et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Emergency Management of Anaphylaxis (2020). Front Pharmacol 2022;13:845689. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.845689 [published Online First: 20220328]

11. Dodd A, Hughes A, Sargant N, et al. Evidence update for the treatment of anaphylaxis. Resuscitation 2021;163:86-96. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.04.010

12. GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software] [program], 2024.

13. de Silva D, Singh C, Muraro A, et al. Diagnosing, managing and preventing anaphylaxis: Systematic review. Allergy 2021;76(5):1493-506. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14580

14. Ko BS, Kim JY, Seo D-W, et al. Should adrenaline be used in patients with hemodynamically stable anaphylaxis? Incident case control study nested within a retrospective cohort study. Scientific Reports 2016;6(1):20168. doi: 10.1038/srep20168

15. Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, et al. Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2014;69(8):1026-45. doi: 10.1111/all.12437

16. Simons FER, Chan ES, Gu X, et al. Epinephrine for the out-of-hospital (first-aid) treatment of anaphylaxis in infants: Is the ampule/syringe/needle method practical? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001;108(6):1040-44. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119916

17. Muraro A, Worm M, Alviani C, et al. EAACI guidelines: Anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy 2022;77(2):357-77. doi: 10.1111/all.15032

18. Dreborg S, Kim H. The pharmacokinetics of epinephrine/adrenaline autoinjectors. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2021;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s13223-021-00511-y

19. Brown SG, Blackman KE, Stenlake V, et al. Insect sting anaphylaxis; prospective evaluation of treatment with intravenous adrenaline and volume resuscitation. Emerg Med J 2004;21(2):149-54. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.009449

20. Alviani C, Burrell S, Macleod A, et al. Anaphylaxis Refractory to intramuscular adrenaline during in‐hospital food challenges: A case series and proposed management. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2020;50(12):1400-05. doi: 10.1111/cea.13749

21. (ASCIA) AASoCIaA. Guideline for the acute management of anaphylaxis 2024 2024 [Available from: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/acute accessed August 14 2024.

22. Ruiz-Garcia M, Bartra J, Alvarez O, et al. Cardiovascular changes during peanut-induced allergic reactions in human subjects. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2021;147(2):633-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.033

23. Gabrielli S, Clarke A, Morris J, et al. Evaluation of Prehospital Management in a Canadian Emergency Department Anaphylaxis Cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7(7):2232-38.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.018 [published Online First: 20190426]

24. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis—a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020;145(4):1082-123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

25. Fischer D, Vander Leek TK, Ellis AK, et al. Anaphylaxis. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2018;14(S2) doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0283-4

26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. Anaphylaxis: assessment and referral after emergency treatment. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

Copyright © NICE 2020. 2020.

27. Pier J, Bingemann TA. Urticaria, Angioedema, and Anaphylaxis. Pediatr Rev 2020;41(6):283-92. doi: 10.1542/pir.2019-0056

28. Wang Y, Allen KJ, Suaini NHA, et al. The global incidence and prevalence of anaphylaxis in children in the general population: A systematic review. Allergy 2019;74(6):1063-80. doi: 10.1111/all.13732

29. Yu JE, Lin RY. The Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;54(3):366-74. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8503-x

30. Sánchez-Borges M, Aberer W, Brockow K, et al. Controversies in Drug Allergy: Radiographic Contrast Media. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7(1):61-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.030 [published Online First: 20181217]

31. Grabenhenrich LB, Dölle S, Moneret-Vautrin A, et al. Anaphylaxis in children and adolescents: The European Anaphylaxis Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137(4):1128-37.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.015 [published Online First: 20160121]

32. Brown JC, Simons E, Rudders SA. Epinephrine in the Management of Anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(4):1186-95. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.12.015

33. Golden DBK, Wang J, Waserman S, et al. Anaphylaxis: A 2023 practice parameter update. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2024;132(2):124-76. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.09.015

34. Simons FE, Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis: Unique aspects of clinical diagnosis and management in infants (birth to age 2 years). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(5):1125-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.014 [published Online First: 20141030]

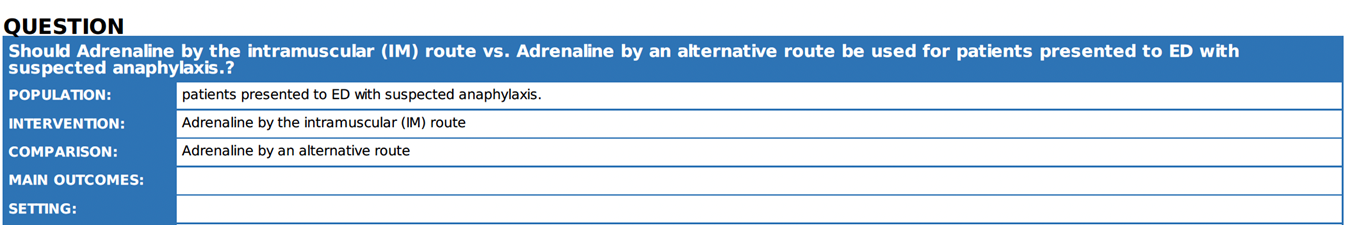

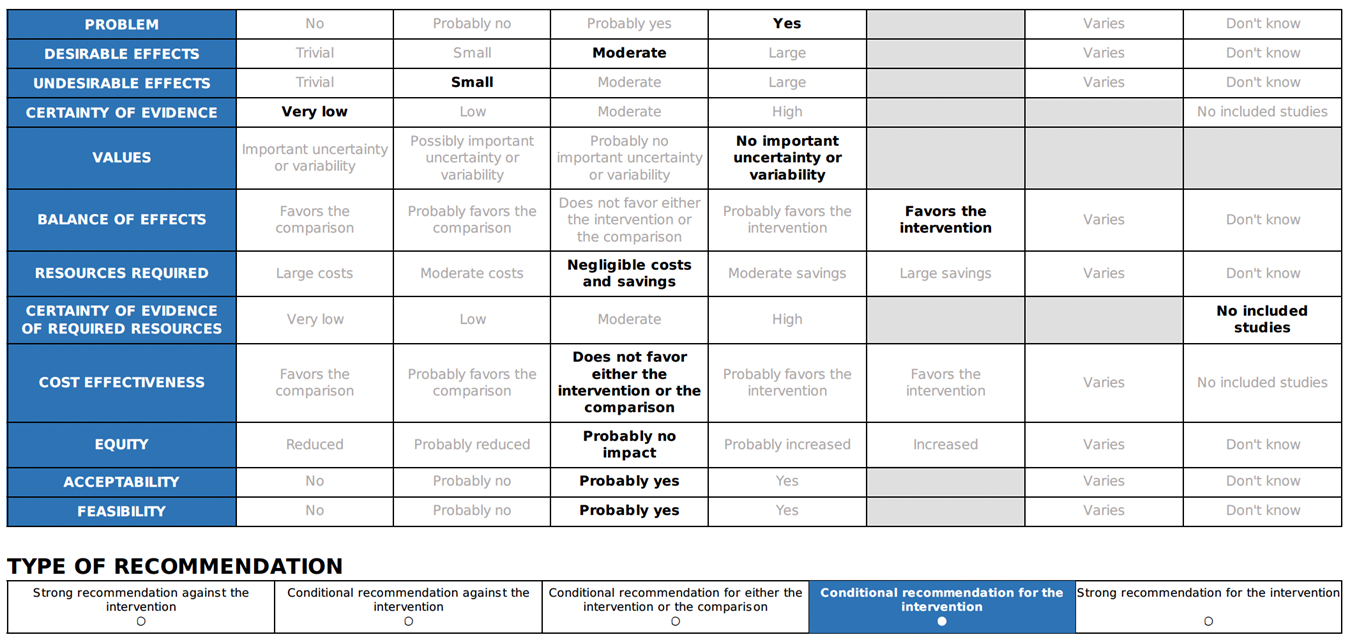

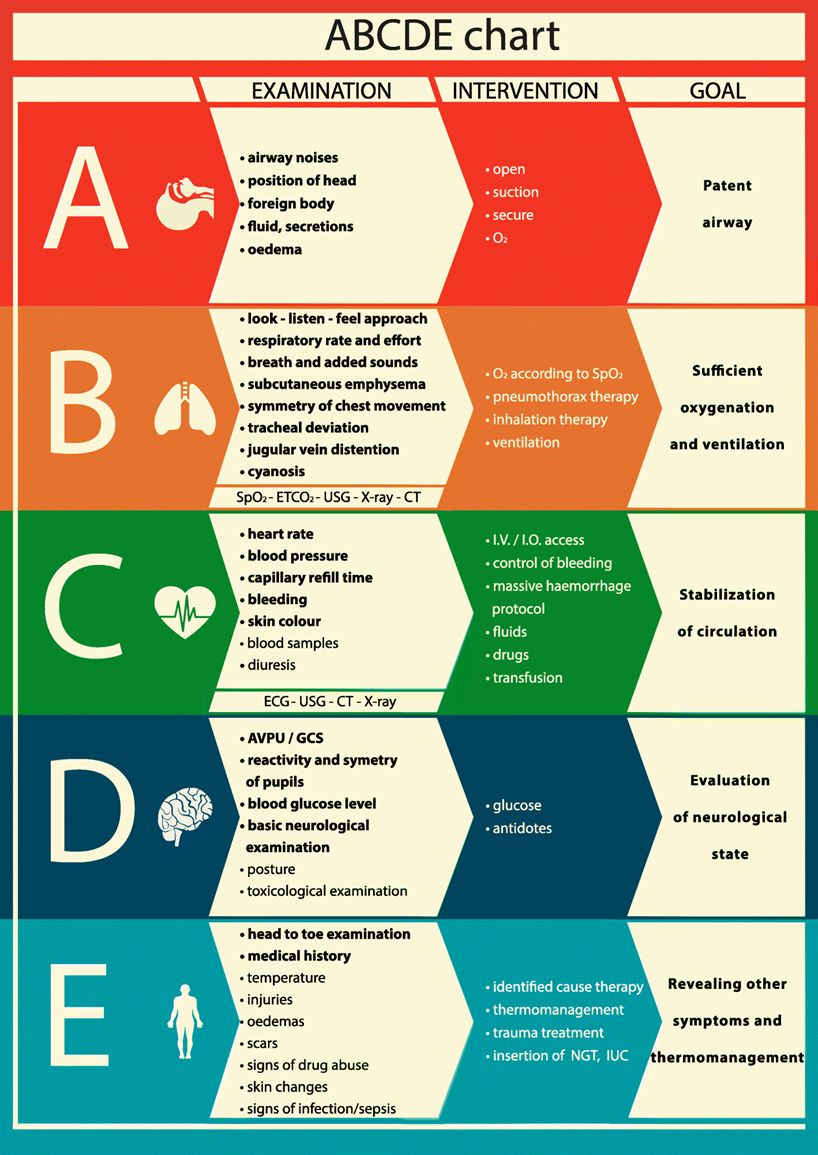

- Annex1- EtD Tables

Annex 2: Recommended ABCDE Approach for managing critically ill patients

Peran, D., Kodet, J., Pekara, J., Mala, L., Truhlar, A., Cmorej, P.C., Lauridsen, K.G., Sari, F., Sykora, R., 2020. ABCDE cognitive aid tool in patient assessment – development and validation in a multicenter pilot simulation study. BMC Emergency Medicine 20.. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00390

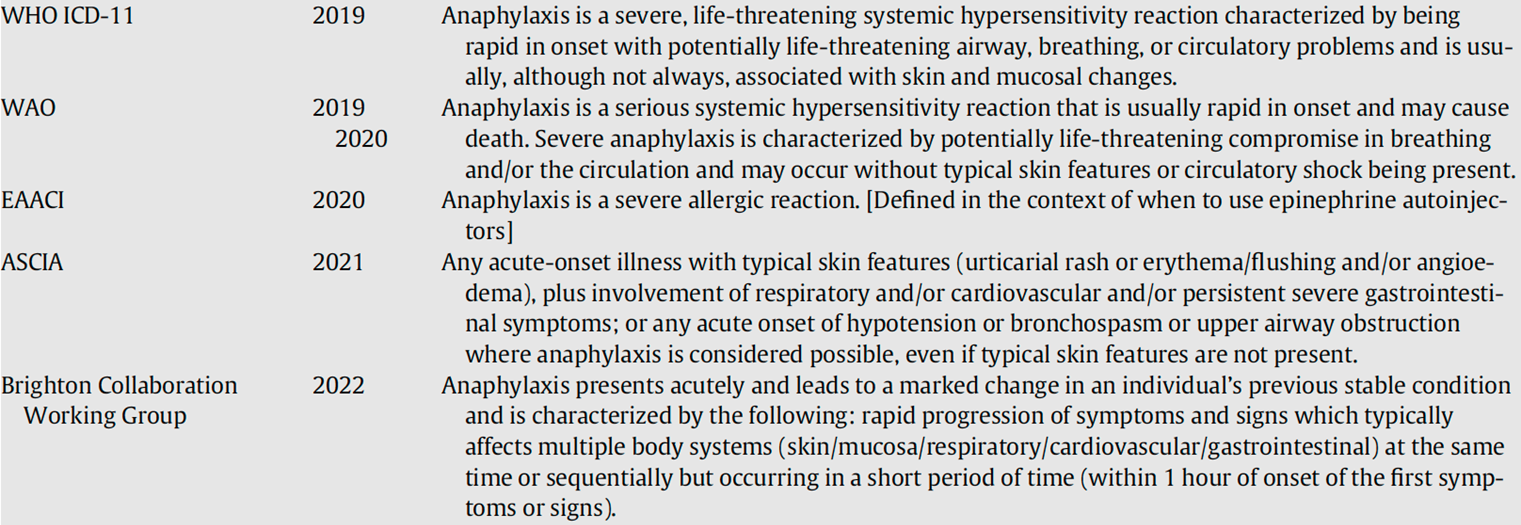

Annex 3: Most recent definitions used for anaphylaxis

ASCIA, Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy; EAACI, European Academy Allergy and Clinical Immunology; WAO, World Allergy Organization; WHO, World Health Organization. Golden DBK, Wang J, Waserman S, et al. Anaphylaxis: A 2023 practice parameter update. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2024;132(2):124-76. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2023.09.015