Methods of slaughter process of food animals

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Food hygiene Guidelines |

| Book: | Methods of slaughter process of food animals |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 10:19 PM |

Description

"last update: 9 Oct 2024"

- Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the committee of National Egyptian Guidelines for Veterinary Medical Interventions, Egyptian Health Council for adapting this guideline.

Executive Chief of the Egyptian Health Council: Prof. Mohamed Mustafa Lotief.

Head of the Committee: Prof. Ahmed M Byomi

The Decision of the Committee: Prof. Mohamed Mohamedy Ghanem.

Scientific Group Members: Prof. Nabil Yassien, Prof. Ashraf Aldesoky Shamaa, Prof. Amany Abbass, Prof. Dalia Mansour, Dr Essam Sobhy

Editor: Prof. Nabil Yassien,Hamdy Abd elhady

- Glossary

Slaughter: defined in the meat hygiene regulations as “killing by blood removal “

- Scope

Intends to teach the meat inspector how to supervise correct slaughter procedures on food slaughtered animals including Halal slaughter procedures, Jewish slaughter of animals, different of animal stunning. Methods of exsanguination following the stunning procedures. Also, recognize advantages and disadvantages of each slaughter method and to be aware of the emergency slaughter legislations and cases.

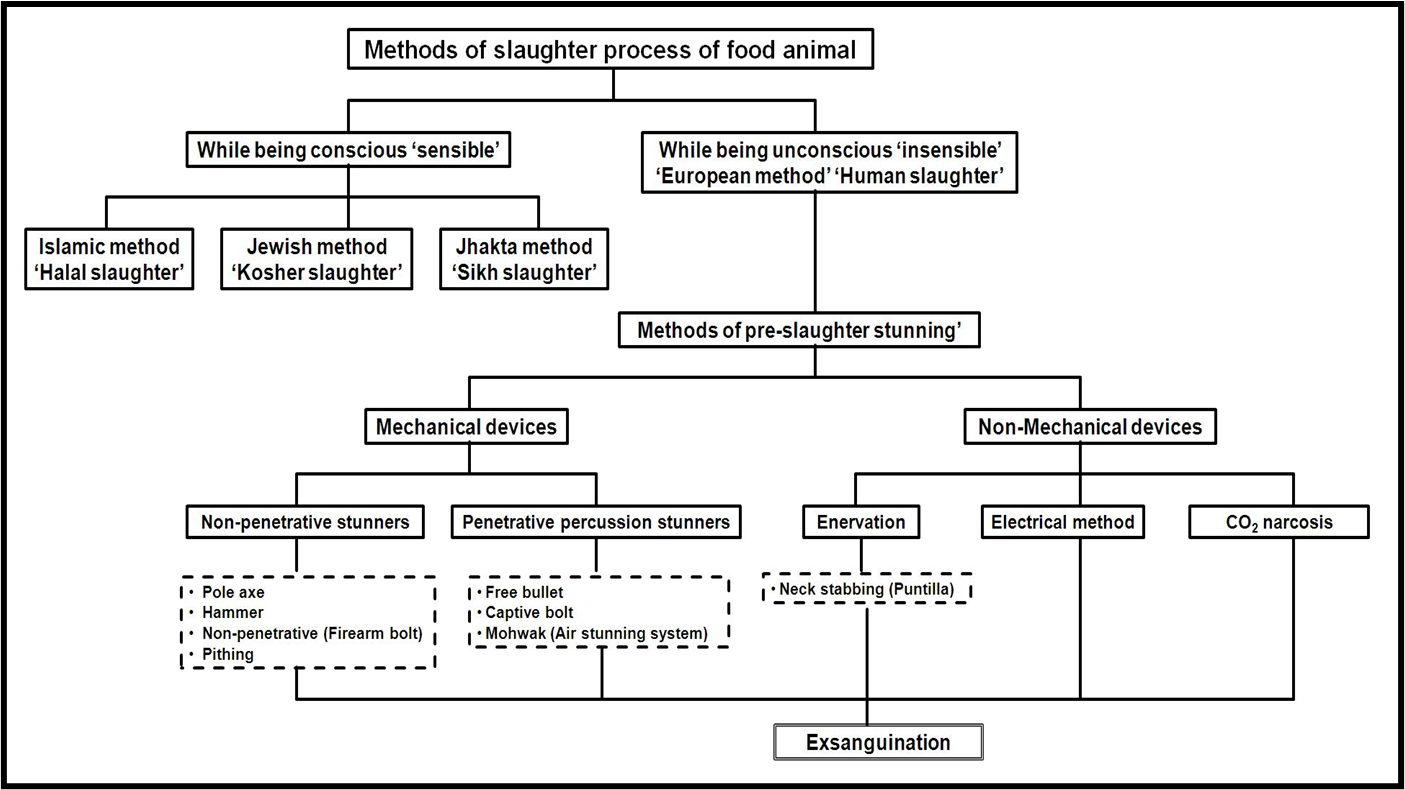

- Classification of slaughter methods

Ritual slaughter

Islamic method (Halal slaughter): derived from verses of the Holy Quran and the saying of profit "hadith". Animal species from Islamic legal position:

1. Indisputably forbidden foods

· Pork, Carrion, Shed blood, Animal dedicated to any other than God, Strangled animals, Fatally beaten animals, Dead through falling from height, Horn butted animals, Devoured by wild beasts, Scarified to idols, slaughtered animals of all non-kitabis.

2. Animals indisputably permissible:

· Sheep, Goats, Cows, Buffaloes, Poultry, Fish and locust (crustacean and Mollusca).

- Procedure of Halal slaughter

· Pre-slaughter rest.

· Forbid cruel treatment of the animals before slaughter (mercy and kindness).

· Knife should be very sharp and forbids sharpening of the knife in front of the animals or slaughtering in the sight of other animals.

Halal slaughter includes three methods:

1. Slaughter (Dabh)

· Severing the animal’s trachea, oesophagus and jugular veins.

· Used in sheep, cows and birds.

2. Slaying (Nahr)

· Cutting the vessels at the base of the neck i.e. the upper part of the chest.

· Used in camels.

3. Stabbing (Aqr)

· Fatally wounding an unmanageable animal.

· Used for wild animals which are lawful to hunt.

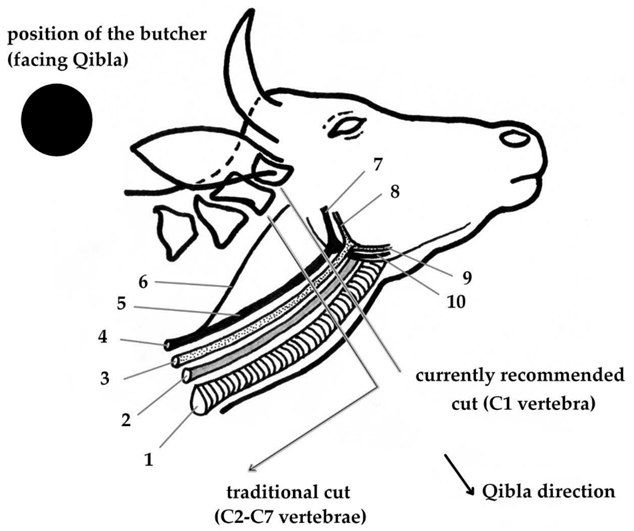

In Halal slaughter the cut must be

Continuous and uninterrupted. The knife must not depressed down vertically but drawn horizontally across the neck. The cut free and must not be a stab. Not be so closed to the chest or too near the head. No laceration or tearing of tissues. Further preparation and dressing of well-bled carcass must be delayed until all signs of life and cerebral reflex disappear.

- Methods of slaughter process of food animals

Location of incision during the halal slaughter of

cattle (ruminants). 1: trachea; 2: oesophagus; 3: vena jugularis externa

dextra; 4: arteria carotis communis; 5: arteria carotis externa dextra; 6:

arteria carotis interna dextra; 7: arteria maxillaris; 8: vena maxillaris; 9:

vena linguofacialis; 10: truncus linguofacialis.

- Inspection of Emergency slaughtered Animals

Carcasses of emergency slaughtered animals must be subjected to a careful inspection because most causes of food poisoning are associated with the consumption of such flesh. Therefore, bacteriological examination of such carcass should be including. Injured or ill animals arrive to the slaughterhouse in one of the following three conditions.

1. The animal may arrive alive but in a moribund state:

Injured should be made to identify the nature of the disease, accident or medicine. Such animals in a moribund state bleed badly and stiffen immediately after slaughter. Judgment depends upon: Bleeding, Setting, The colour of fat and serous membranes, Causes of conditions, the condition of the meat.

2. The animal may arrive slaughter and uneviscerated:

All animals slaughter outside the abattoir, no matter what explanation is offered by the owner as to the cause of the death, it is necessary to examine a blood smear from the ear or tail, only when it is proved that the animal slaughter is not due to anthrax should the unless slaughter has occurred less than an hour or two previously coldness of the extremities and in cattle, evidence of tympanitis in the left flank are indication that slaughter has not been recent. In sheep which have been dead for some hours the wool is easily pulled out and tympanitis will be observed in the left flank.

Special attention should be paid to the condition of the uterus for sign of septic metritis, intestines for enteritis and the serous membranes for putrefaction. Judgment depends upon the bleeding condition, setting and the condition of the meat. Generally the carcasses which bleed badly their setting is lacking and signs of putrefaction are seem of the pleura and peritoneum and the carcasses are condemned.

3. The animal may arrive slaughtered but bleed and eviscerated:

These carcasses are very difficult to judge specially if they are not accompanied by the internal organs. It is advisable to condemn the carcass if it is not accompanied by some of the organs but an important one is missing, the carcass must bacteriologically examine, or otherwise condemned. Especially attention should be made to the examination of the carcass lymph nodes for enlargement, hemorrhages or tuberculosis and to the kidneys for degree of bleeding.

The degree of congestion and setting of the carcass should also be noted, and if a bovine carcass shows any degree of congestion a smear from the kidney or lymph node should be examined microscopically for anthrax. The vertebrae in cattle should be examined for tuberculosis caries and the pleura and peritoneum for evidence for stripping, while an incision should be made into the musculature for the presence of any abnormal odour and should this be detected a portion of meat should be subjected to a boiling test. This uterus should be examined for septic metritis, the udder for septic mastitis and the intestines for enteritis. In emergency slaughtered animals, only in cases where the animal has been a short slaughtered, shows no evidence of disease (result of bacteriological examination is satisfactory) and in which the carcass sets and looks normal in every way, should been considered fit for consumption. If setting is lacking and signs of putrefaction are seen on the pleura and peritoneum the carcasses should be condemned.

- References

1. Gracey's Meat Hygiene, 11th Edition David S. Collins (Editor), Robert J. Huey (Editor) (2014)

2. Manual on meat inspection for developing countries (No. 119). Food & Agriculture Org..Herenda, D. C., & Chambers, P. G. (1994).

3. Meat Science And Application (2001) by Hui H.Y. et al.

4. Barnett, J.L., Cronin, G.M. and Scott, P.C. (2007) Veterinary Record, 160, 45–49.

5. Bates, G. (2010) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 237 (9), 1024–1026.

6. Bremner, F. (1954) Brain Mechanisms and Consciousness (ed. J.F. Delafresnaye), Oxford University Press, London. Coore, R.R., Love, S., McKinstry, J.L. et al. (2005) Journal of Food Protection, 68 (4), 882–884.

7. Dunn, C.S. (1990) Veterinary Record, 26, 522–525. Ewbank, R., Parker M.J. and Mason C. (1992) Animal Welfare, 1, 55–64.

8. Farm Animal Welfare Council (2003) Report on the Welfare of Farmed Animals at Slaughter or Killing – Part 1, Red Meat animals, DEFRA Publications, London.

9. Garland, T.D., Bauer, N. and Bailey, M. (1996) The Lancet, 348, 610.

10. Gibson, T.J., Johnson, C.B., Mellor, D.J. and Stafford, K.J. (2009) New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 57, 77–95.

11. Grandin, T. (1980) International Journal of the Study of Animal Problems, 1 (6), 375.

12. Gregory, N.G. and Wilkins, L.J. (1989a) Journal of Science of Food and

13. Agriculture, 47, 13–20.

14. Gregory, N.G. and Wilkins, L.J. (1989b) Veterinary Record, 124,

15. 530–532.

16. Lambooij, D.L.O. (1996) Meat Focus International (April), pp. 124–125.

17. Lumb, W.V. and Jones, E.W. (1973) Veterinary Anaesthesia. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 338–340.

18. Perez-Palacios, S. and Wotton, S.B. (2006) Veterinary record, 158, 654–657.

19. Raj, A.B.M. (1999) Veterinary Record, 144, 165–168.

20. Raj, A.B.M. and Gregory, N.G. (1993) Veterinary Record, 133, 317.

21. Raj, A.B.M. and Gregory, N.G. (1994) Veterinary Record, 135, 222–223.

22. Raj, A.B.M. and Gregory, N.G. (1995) Animal Welfare, 4, 273–280.

23. Rosen, S.D. (2004) Veterinary Record, 154, 759–765.

24. Shaw, N.A. (2002) Progress in Neurobiology, 67, 281–344.

25. Thorpe, W.H. (1965) The assessment of pain and stress in animals. Appendix III. Report of Technical Committee to enquire into the

26. welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems. Cmnd 2836. HMSO, London. Van der Wal, P.G. (1983) in Stunning Animals for Slaughter (ed G.

27. Eikelenboom), Martinus Nijhof, The Hague. Warriss, P.D., Brown, S.N. and Adams, S.J.M. (1994) Meat Science, 38, 329–340.

28. Wotton, S.B., Gregory, N.G., Whittington, P.E. and Parkman, I.D. (2000) Veterinary Record, 147, 681–684.