Infertility in Cattle

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Theriogenology Guidelines |

| Book: | Infertility in Cattle |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 24 December 2024, 12:59 AM |

Description

"last update: 25 Sep. 2024"

Table of contents

- - Acknowledgment

- - Abbreviations

- - Glossary

- - Scope

- - Forms of Infertility

- - The possible Causses of Infertility

- 1- Congenital Causes of Infertility

- A) Ovarian congenital affections

- B) Congenital affections of the fallopian tubes

- C) Congenital affections of the Uterus

- D) Congenital affections of the Cervix

- 2- Pathological Causes of Infertility

- A) Ovarian pathological affections

- B) Pathological affections of fallopian tubes:

- C) Pathological affections of the uterus

- D) Pathological affections of the cervix:

- 3- Hormonal Causes of Infertility

- A) Cystic Ovarian Disease (COD)

- B) Adrenal virilism

- C) Delayed ovulation

- 4- Environmental Causes of Infertility

- A) Effect of heat stress

- B) Photoperiodism

- C) Nutrition

- - Body Condition Score (BCS) in Cattle

- - Summary of cattle Infertility Cases Treatment & Interference

- - References:

- Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the committee of National Egyptian Guidelines for Veterinary Medical Interventions, Egyptian Health Council for adapting this guideline.

Executive Chief of the Egyptian Health Council: Prof. Mohamed Mustafa Lotief.

Head of the Committee: Prof. Ahmed M Byomi

The Rapporteur of the Committee: Prof. Mohamed Mohamedy Ghanem.

Scientific Group Members:

Prof. Nabil Abd Elgaber, Prof. Ashraf Aldesoky Shamaa, Prof. Amany Abbass, Prof. Dalia Mansour, Dr. Essam Elmarakby. Dr. Mohamed Elsharkawi, Prof. Gamal Sosa, Dr. Naglaa Radwan, Dr. Hend Elsheikh

Authors: Prof. Gamal A.M. Sosa, Prof. Mohamed M.M. Kandiel, Prof. Ahmed R.M. H.Elkhawagah

- Abbreviations

COD: Cystic Ovarian Disease

FT: Fallopian Tube

GF: Graafian Follicle

CL: Corpus Luteum

AI: Artificial Insemination

ET: Embryo Transfer

E: Endometritis

HSP: Heat Shock Proteins

NEB: Negative Energy Balance

MES: Milk Energy Secreted

ME: Maintenance Energy

EI: Energy Intake

- Glossary

Infertility: The temporal inability of the female either to produce a viable ovum ready to be fertilized or to keep embryos till normal parturition.

Anestrum: The female is not observed in estrus either because she has not come into estrus (not cycling) or because estrus was not detected (cycling).

Abortion: When one or more calves are born dead or survive for less than a day when born between 152 and 270 days after successful service.

Repeat breeder: the female animal is called as repeat breeder when it has failed to conceive even after three or more services, has normal estrus cycle length, no abnormality in the vaginal discharge, and no palpable abnormality in the reproductive tract.

Artificial insemination (AI): The service of a cow by inserting frozen bull semen into a cow’s uterus. This allows the selection of high-quality genetics and avoids the risks of keeping a mature bull on the farm.

Biotechnology: Technology that utilizes biology to reap benefits for the herd. Often this involves creating or modifying DNA to select optimum genetic traits.

Calving: The birth of one or more calves more than 270 days following an effective service.

Calving rate: This is the total number of services received by a group of cows which results in calving as a percentage of the total number of services.

Calving interval is the

number of days between two consecutive calvings. Calving interval covers both

return to cyclicity and conception

Conception: Conception is the act of

becoming pregnant through fertilization and implantation of

the fertilized egg onto the lining of the uterus.

Cull cow: A cow that is removed from the herd.

Dairy nutritionist: Expert animal health consultants who advise on the nutritional needs of cows. They help recommend the best diets for maximizing the fertility of each cow.

Date of conception: The date of the effective service.

Date of service: The date of the first natural mating or artificial insemination.

Days open is the interval between calving and the last insemination date.

Embryo: The developing calf from the date when it was conceived to the 42nd day of the cow’s pregnancy.

Embryo loss: When a developing calf does not survive during the first 42 days of pregnancy.

Fetus: The developing calf from day 43 to birth.

Fetal loss: When a fetus dies between 43 and 151 days of pregnancy.

Estrus: The physiological state whereby a cow will voluntarily stand to be mounted.

Estrous cycle: The regular advent of estrus / coming into heat, comes with a change in the genitals and reproductive hormones.

Estrous cycle length: Duration of time from the start of the estrus cycle to the beginning of the next. The start of the first estrus is counted as Day 0.

Gestation period: The number of days between conception and birth.

Heat detection rate (HDR): The percentage of eligible females that are seen or detected in heat. In a perfect system, this would be 100%.

Heifer: A mature female cow that is yet to give birth.

Non-return rate is a binary measure of whether a new mating or insemination event occurs after the first insemination within a time period.

Premature calving: This term refers to the birth of one or more calves between 152 and 270 days after an effective service. The calf must survive for 24 hours or more.

Stillborn calf: A calf that has been birthed dead or found dead after an unobserved calving.

Pregnancy Rate (PR): This can also be known as Reproductive Efficiency. It is an American KPI that is rapidly being adopted in the UK. It’s the product of HDR/SR and CR. For example, in a herd, if 50 animals are eligible in one 21-day period: 40 are inseminated (40/50 = 80% SR); 20 of those cows become pregnant (20/40 = 50% CR).

- Scope

This Guideline is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of infertility problems in domestic animals. It is targeting the farm and pet animals. It gives a brief description of the different types and causes of infertility with the proper line of treatment.

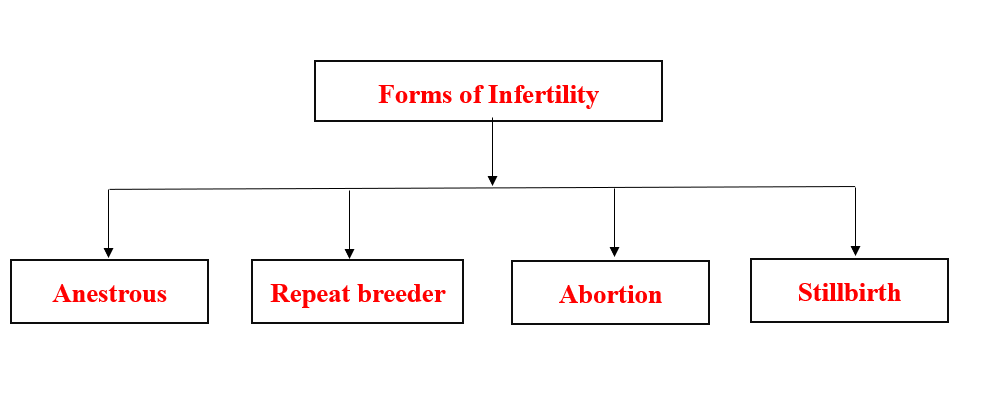

- Forms of Infertility

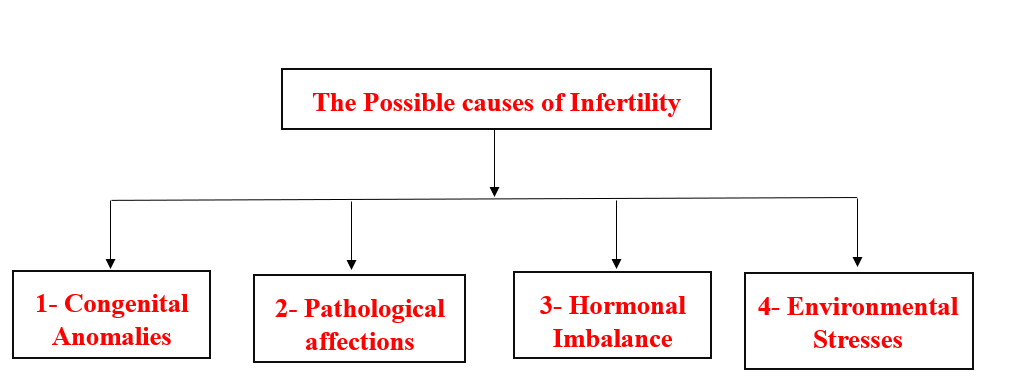

- The possible Causses of Infertility

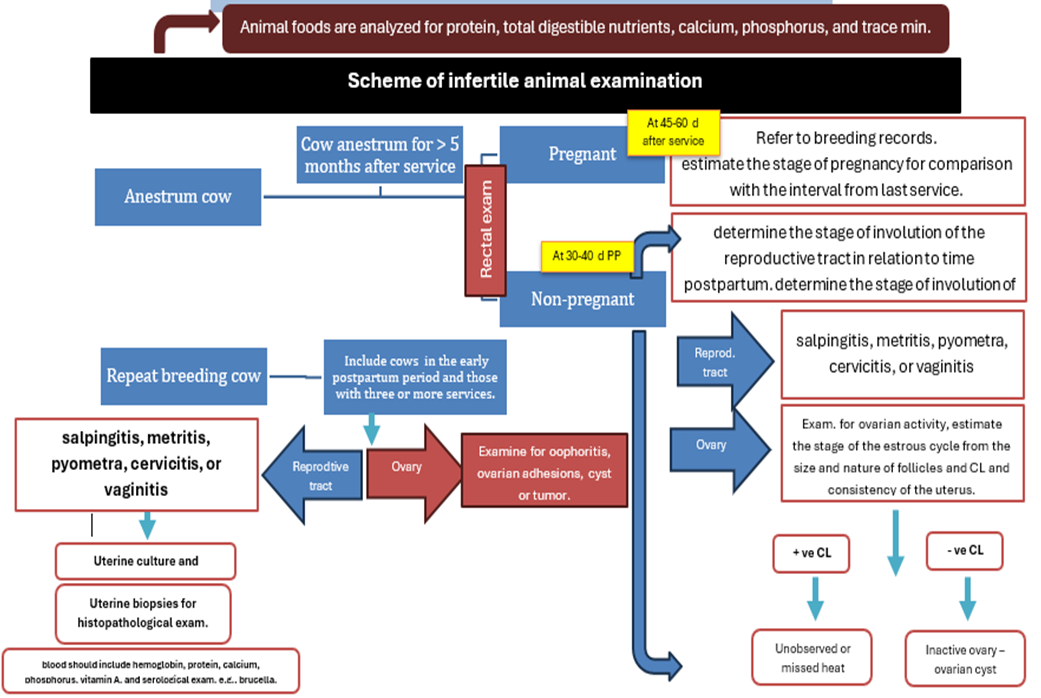

Scheme of infertile cow examination (concluded from Morrow, 1970)

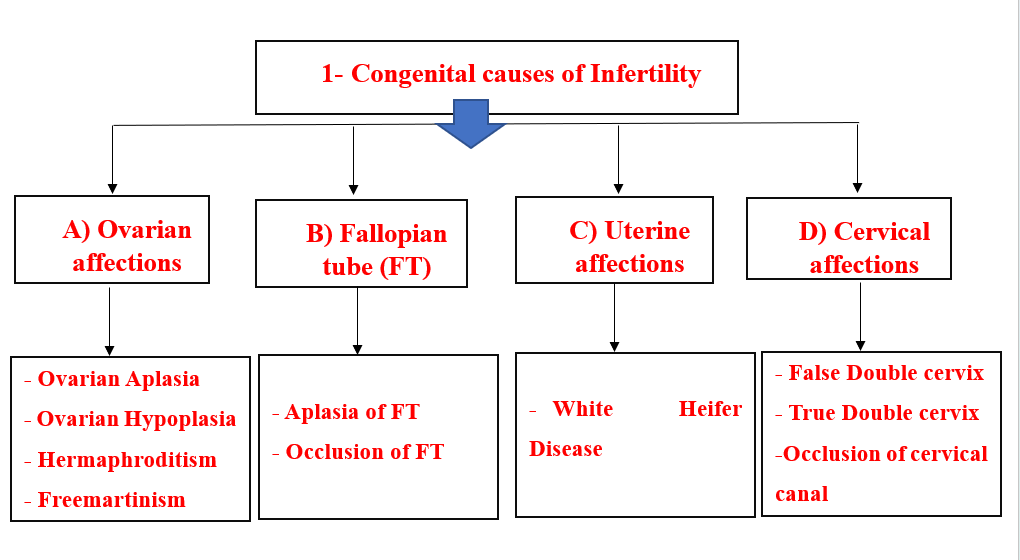

1- Congenital Causes of Infertility

A) Ovarian congenital affections

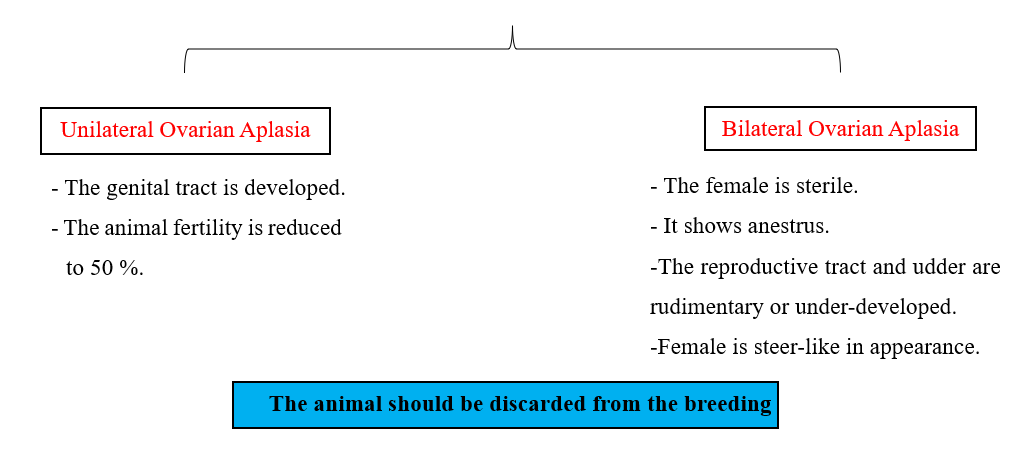

1- Ovarian aplasia (Agenesis):

- Heifers show the absence of one or both ovaries.

- It may be bilateral or unilateral.

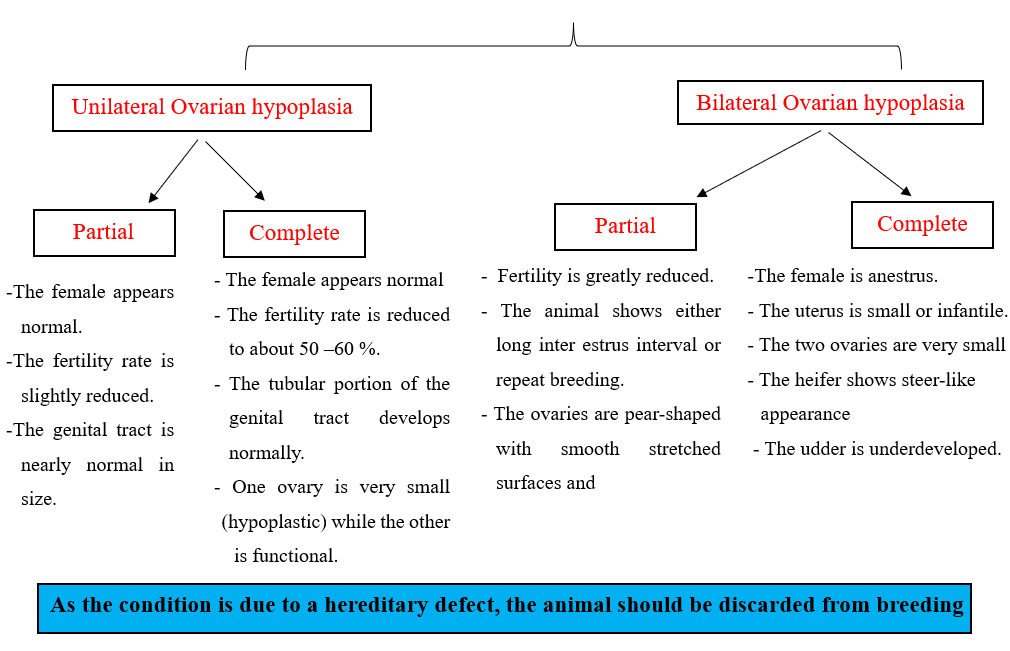

2- Ovarian hypoplasia:

- Incomplete development of the ovary with weakness or deficiency of germ cell due to the failure of migration of primordial germ cells from the yolk sack to the developing gonad during embryonic stage.

- It may be of genetic origin due to a single recessive gene with incomplete penetration.

- It may be associated with an adverse environmental condition.

- In the Swedish Highland breed of cattle, hypoplasia is caused by a single recessive autosomal gene.

- Serum Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) levels in affected females are lower (below 0.5 ng/ml) than normal females.

- The hypoplastic ovary is small (difficult to find), thin narrow structure of firm consistency, and cord- like thickening.

- It may be unilateral or bilateral.

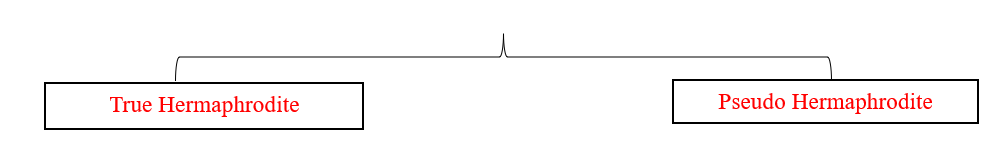

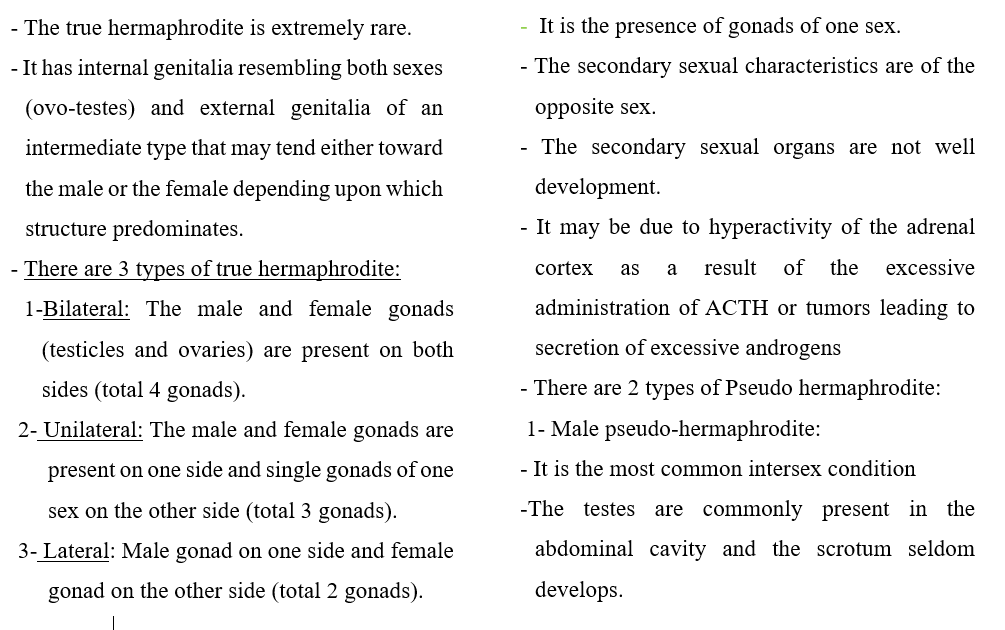

3- Hermaphrodism (Intersex or sex reversed):

- The two sex organs are present in one animal.

- It occurs in all species of animals but most commonly in hornless goats and pigs.

- Types of hermaphrodites:

4- Freemartinism:

- Co–twinning of a heifer to a male brother (Sexually different dizygous twins).

- About 90% of these heifers are sterile.

- It is due to the underdevelopment of the female genital organs during the intra-uterine life.

- The freemartin heifer is characterized by:

- Anestrous

- Steer–like appearance with high limbs and abnormally large ox horn.

- Small narrow pelvis and vulva, prominent clitoris, and coarse vulvar hair and resembles the preputial tuft.

- The udder is ill-developed with small teats.

- Diagnosis:

1- Clinical signs:

- Upwards spurts of urine

- An enlarged clitoris

- A fish-hook vulva confers a different angulation of the external genitalia onto the perineum

2- Karyotyping: Karyotyped by leucocyte culture shows sex-chromosome chimeras. Cytogenetic examination can demonstrate XX and XY chromosome patterns in freemartins.

3- Rectal examination: The ovaries and the uterus usually cannot be palpated and rudimentary. The cervix is absent (diagnostic of the condition).

4- Vaginal examination:

- On vaginal examination, the vagina is short, narrow with a blind vestibule.

- “Fincher pencil test “i.e. when a pencil or test tube is inserted into the vagina, it does not proceed beyond the external urinary meatus. In calves 1–4 weeks old, the normal vaginal length is 13–15 cm, whereas in a freemartin vaginal length is 5–6 cm.

- Vaginal length is easily measured by gently inserting a well-lubricated “Freemartin Probe” (7 cm length) with a blunt end into the vagina.

5- Serum anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) levels measurement: AMH in freemartin animals are 10-72 pg/ml.

6- hCG challenge test: no increased in estradiol or progesterone post-test.

B) Congenital affections of the fallopian tubes

1- Aplasia of the fallopian tube:

- It is the absence of one or both tubes due to the arrested growth of the anterior third

of the Mullerian ducts.

- It is associated with agenesis or segmental aplasia of the uterus.

- It may be unilateral or bilateral, partial or complete.

- In unilateral aplasia, the fertility is reduced.

- In bilateral aplasia, the animal is sterile.

- The animal shows estrus as the ovaries are normally developed and active.

2- Occlusion of the fallopian tubes.

- The Mullerian duct fails to canalize.

- It may be bilateral or unilateral.

- In unilateral cases, the fertility is reduced.

- In bilateral cases, the animal is sterile.

- Cystic dilatation of the fallopian tube is the sequence of occlusion of the fallopian tubes.

C) Congenital affections of the Uterus

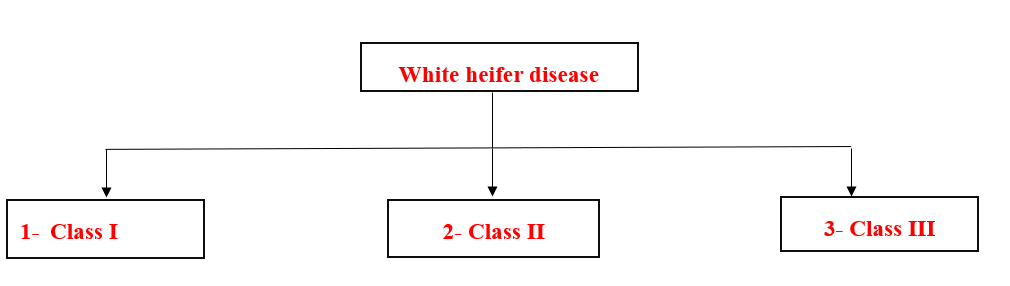

- White heifer disease:

- Commonly observed in white heifers of the short horn breeds (such as Belgian Blue and Shorthorn), caused by a single recessive sex-linked gene to the white color.

- Very rare in other cattle breeds.

- The embryonic development of the anterior vagina, cervix, and uterus of the heifer is arrested in varying degrees.

-The ovaries and fallopian tubes are normal.

- There are three types of white heifer disease based on the site of the defect as follows:

1- Class (I) of the white heifer disease:

- It is the most severe type.

- Characterized by:

- The presence of hymeneal constriction

- Absence of either the cranial part of the vagina, the cervix or the uterine body.

- Cystic dilatation of the uterine horns with yellow to dark reddish-brown mucus.

- Normal heat with repeat breeding followed by anestrus due to blockage of PGF2œ receptors.

2- Class (II) of the white heifer disease (Uterus unicorns, one horn).

- One mullerian duct fails to differentiate into uterine horn, while the other develops normally.

- The hymnal constriction usually is not present.

- The animal shows signs of estrus but infertile.

- Repeat breeding is the common signs of this form.

3- Class (II) of the white heifer disease

- Characterized by the presence of complete imperforated hymen.

- The rest of the genital tract is normal.

- Accumulation of the estrous mucus which is usually amber to dark brown.

- Occasionally, infection may be present, and the imperforated hymens retain a large amount of pus.

- The female becomes anestrum.

- In all cases:

- Service by A.I. is impossible, while normal coitus by the bull in classes (I and III) is

frequently followed by slight hemorrhage and straining.

- If the vaginal distention becomes large (Case I & III), distended bulging of the hymen will appear between the vulvar tips with each abdominal pressing.

- It should be differentiated from pregnancy, freemartins, and pyometra.

- For hereditary reasons, these animals should be discarded. In class (III), an incision of the imperforated hymen can be done.

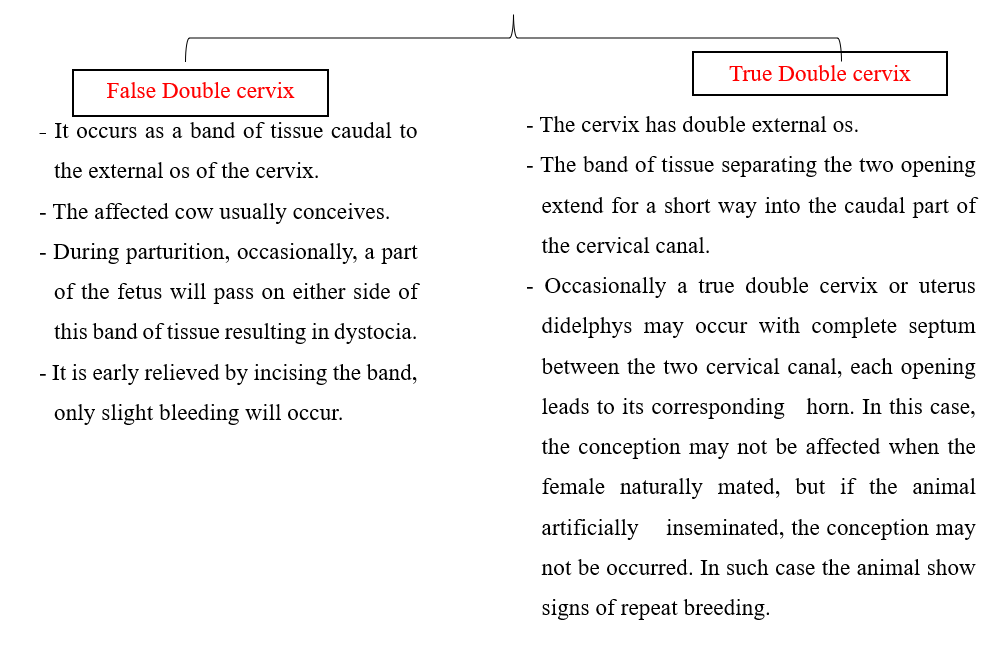

D) Congenital affections of the Cervix

1. Double Cervix

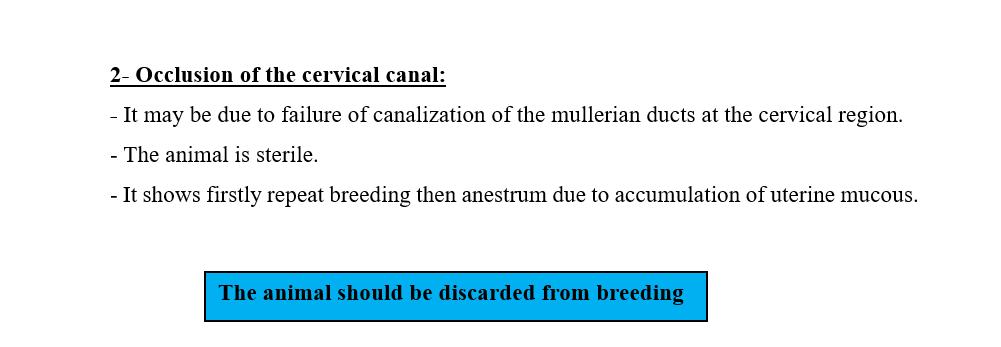

2- Pathological Causes of Infertility

A) Ovarian pathological affections

1- Ovaritis (oophoritis):

- Inflammation or inflection of the ovary.

- The possible causes are:

1- Mechanical e.g., rough manipulation during rectal examination, massage, inoculation of CL, and rupture of cysts.

2- Infection occurs either by:

- Extension from perimetritis, parametritis and peritonitis.

- Ascending through the fallopian tube and uterus in case of pyometra and metritis.

-McEntee (1990) described cases of tuberculous oophoritis, brucella-induced oophoritis, and ovarian abscessation in animals that that have had generalized pyemia.

- The affection of the right ovary is more common than the left one because the right is more functioning.

- Slight adhesion with the ovarian bursa hinders the passage of the ovum to the fallopian tubes resulting in repeat breeding.

- When extensive adhesion is present, pressure atrophy on the ovary may result in anestrus.

- Transrectal ultrasound shows a hyperechoic mass on the affected ovary.

- Prognosis is unfavorable especially when there is extensive ovario-bursal adhesion.

- Prevention is more important than treatment.

- Bilateral cases with dense adhesion should be fattened and slaughtered because it is sterile.

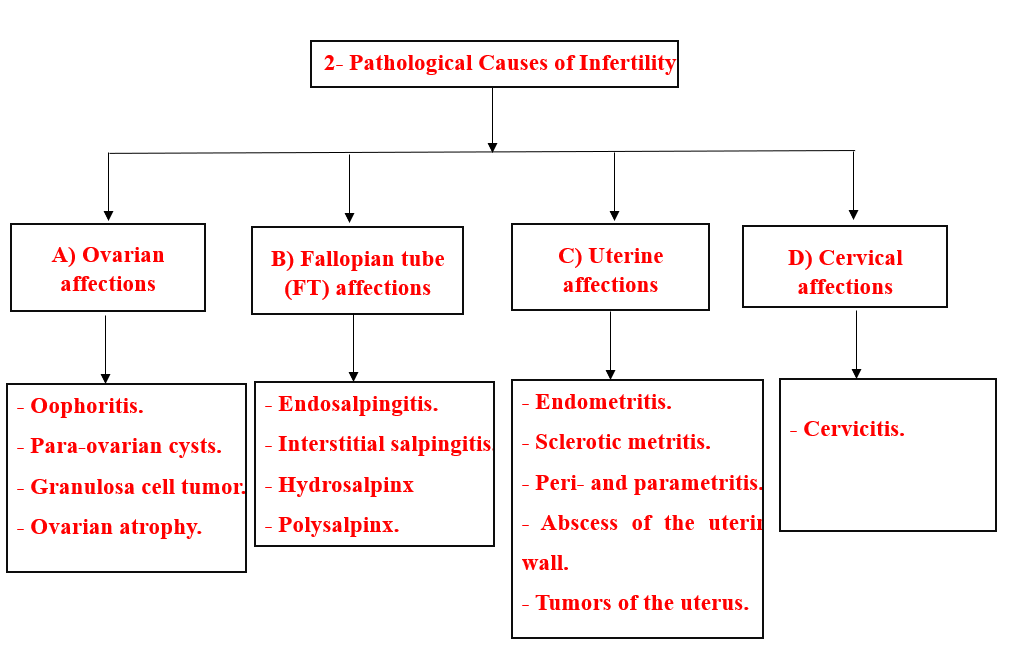

2- Para-ovarian cysts:

- Cystic dilatation of the remnants of the Wolffian ducts neighboring to the ovary (meso-salpinx).

- The cyst may reach a large size, about 10 inches, round or oval in shape, and interfere with the fertility of the animal but this is rare.

- Normally, they are 2-5 cm in diameter and do not interfere the fertility.

Paraovarian cyst in buffalo heifer nearby the ovary that had corpus luteum. Paraovarian cyst (POC) appeared as a large translucent anechoic cavity.

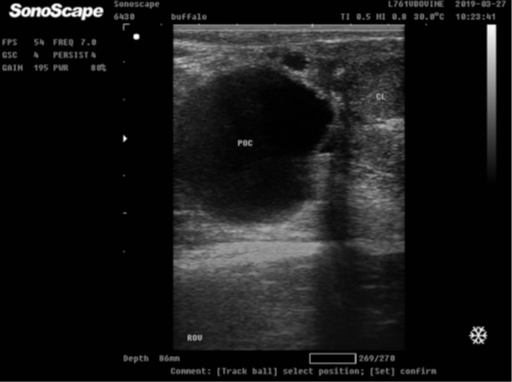

3- Granulosa cell tumor:

- It is the most common affection in cattle.

- They can reach a large size to a child head with irregular surface and fleshy texture.

- When there is a tumor in one ovary, atrophy of the other ovary may occur due to high estrogens produced by the granulosa cell tumor in the affected ovary.

- The affected animal shows signs of nymphomania due to continuous secretion of estrogen with relaxation of pelvic ligaments.

- Heifers are anestrous if the level of estrogen is so high to block the symptoms of nymphomania.

- The tumor should be differentiated from follicular cysts by rectal examination. The cyst is fluctuating, never exceeding 8cm in diameter and having a smooth convex regular surface.

- Diagnosis of granulosa cell tumor depends on a history of nymphomania, anestrus, and lactation in heifers.

- The weight and size of a large ovarian tumor tends to drag the ovary downward and forward into the abdominal cavity. The other ovary may be atrophied and small.

- Uterus first is turgid and erected then becomes fleshy and flaccid.

- Treatment by ovariectomy of the affected ovary. The other ovary, consequently, becomes functioning.

Granulosa Cell Tumor in Goat

4- Ovarian atrophy:

- Pressure atrophy due to tumor, endocrine disturbances or pressure by the surroundings.

- Senile atrophy due to old age.

- Animals show signs of anestrum for a long period.

- Animal is sterile due to loss of ovarian activities

B) Pathological affections of fallopian tubes:

- Mostly cause infertility by repeat breeding.

- Common in the cow than in the mare due to the direction of genitalia, and the utero-tubal junction is guarded by muscular papillae in the mare.

- Affections of the fallopian tubes are caused by:

-- Ascending infection from the uterus.

-- Bad massage of the ovary.

-- Tuberculosis of the oviduct.

- The pathological affections of oviducts are:

1- Endo-salpingitis:

- Inflammation of the oviducts without significant enlargement.

- It is usually bilateral and cannot be detected rectally.

2- Interstitial salpingitis:

- Catarrhal exudates collect in the lumen.

- The mucosal folds have cellular infiltration.

- Changes in the whole wall of the tube.

- The tube is pencil-like and very hard.

3- Hydrosalpinx:

- Accumulation of fluid in the fallopian tube.

- It may be unilateral or bilateral.

- It is a sign of the white heifer disease.

4- Pyosalpinx:

- Pus is present in the fallopian tube and obstructs its lumen.

- The pus is doughy, and the wall is thick.

- It usually follows severe uterine infection and associated with severe adhesions

of the mesosalpinx and mesovarium.

- Diagnosis of the pathological effects of the oviducts depends on:

-- History of repeat breeding,

-- Positive rectal examination.

-- Some diagnostic tests:

* Rubin's insufflation technique: Carbon dioxide is passed into the uterus under pressure of 60 - 100 mmHg. If the oviducts are normal, the pressure gradually falls to 40 - 60 mmHg.

* Starch test: About 30 gm starch in 500 ml distilled water is injected intraperitoneally. Vaginal mucous smears are tested by diluted iodine solution (one-part Lugol to 50 parts water) at 12 - 24 hours intervals for 2 - 4 days. The blue color indicates patent one or both oviducts.

- Prognosis is poor and treatment is unfavorable or not satisfactory.

- Treat pyometra or endometritis.

- Carbon dioxide insufflation may break down adhesion.

- Intramuscular and intrauterine antibiotics are helpful.

C) Pathological affections of the uterus

1- Endometritis:

- Inflammation of the endometrium of the uterus.

- Infertility from the absence of suitable media due to the toxic influence of the exudates on the sperm and ovum.

-The possible causes of endometritis are:

-- Abnormal parturition; abortion dystocia, Fetotomy, and retention of placenta.

-- Delayed uterine involution.

-- Pneumo-vagina or wind sucking,

-- Following Coitus; infected semen or prepuce

-- Unhygienic births help.

-- Unhygienic instruments; treatment or insemination.

-- Vaginal or uterine prolapse.

-- Hormonal disturbance which influences the natural defensive mechanism of the female genitalia against the saprophytic and non-saprophytic microorganisms

-- Blood or endogenous infection from a septic focus in the body (clow or udder affection).

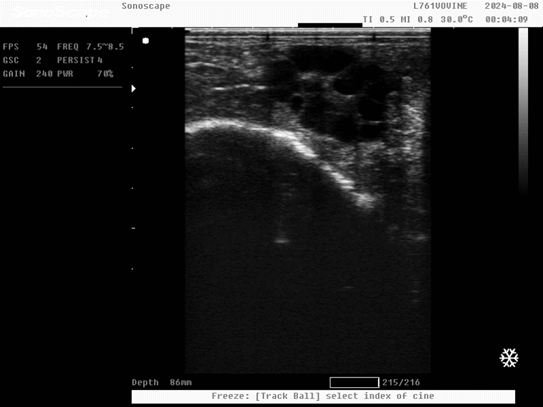

- Endometritis can be divided into four degrees as follows.

1- Chronic catarrhal endometritis (E1):

-- Failure of conception.

-- Regular estrus and mating with good fertile bull.

-- There is no abnormal vaginal discharge.

-- Estrous mucus is slightly increased and turbid.

-- Rectally, no abnormalities in the uterus.

-- The animal is typically a repeat breeder.

2- Chronic mucopurulent endometritis (E2):

-- Increased, milky, or cloudy mucus with pus flakes.

-- The abnormal discharge is seen on/off estrus.

-- Rectally, the uterus is slightly enlarged, flabby, and thickened.

-- The cervix is felt slightly larger and flabby.

-- Vaginally, the cervix is congested and enlarged.

-- It is commonly associated with chronic cervicitis.

-- The animal is a repeat breeder.

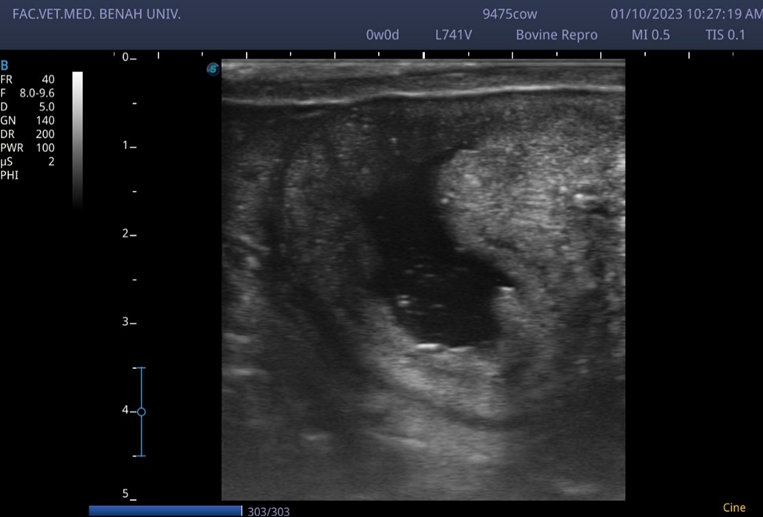

Chronic endometritis in cow characterized by the presence of a hypoechoic inflammatory exudate contains a hyperechoic exfoliated cells and neutrophils inside the uterine lumen give it snow storm like appearance (notice the gray-black color of the inflammatory fluid)

Chronic endometritis in cow characterized by the presence of a hyperechoic masses inside the uterine lumen (notice the white color of the inflammatory aggregate)

3- Purulent endometritis (E3):

-- The inflammation is deeper,

-- Constant mucopurulent and purulent discharge.

-- The discharge is copious with bad odor.

-- Rectally, the uterus is large, thick, fluctuates, and hangs down or over the pelvic pubis.

-- The cervix is also enlarged and indurated.

-- Vaginally, enlarged, red, flabby, and widely opened cervix.

-- The Animal is a repeat breeder.

4- Pyometra (E4):

-- Collection of large amounts of pus in the uterus.

-- It will be associated with the persistence of the corpus luteum

-- The animal shows signs of anestrus.

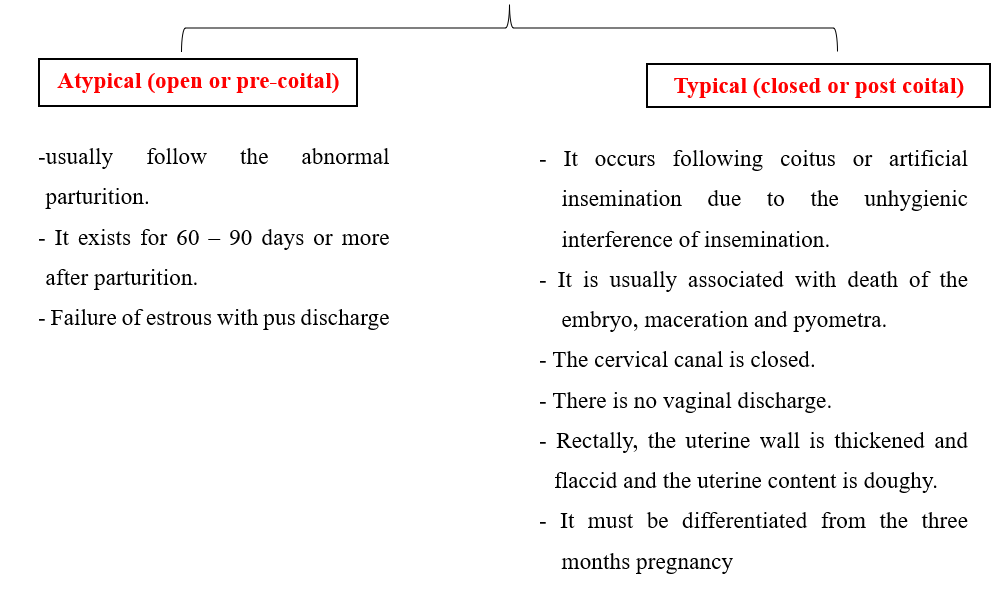

- There are 2 types of pyometra:

- Diagnosis of endometritis:

-- History of repeat breeding,

-- Rectal examination with ultrasonography.

-- Vaginal examination.

◾Clinical endometritis in cows can be diagnosed by use of a vaginal discharge collection device or vaginoscopy or based on purulent discharge in the perineal area. The presence of more than 50% in the sample collected after 21 days after parturition can be used as a criterion to diagnose clinical endometritis.

◾ Subclinical endometritis in cows is diagnosed through the collection of a uterine lumen sample for cytologic evaluation using either cytobrush or cytotape techniques or uterine lavage. A threshold to characterize subclinical endometritis has been described: >18% PMNs in samples collected at 20–33 days after parturition or >10% PMNs in samples collected at 34–47 days after parturition.

- Because endometritis is a subclinical (no signs or symptoms) disease, diagnosis via a Metricheck™ device is necessary. A Metricheck™ device is a rubber diaphragm (similar to a small tennis ball cut in half) on the end of a stainless-steel rod, which is inserted into the cow’s vagina and used to collect a sample of discharge from the uterus. If pus is detected using this procedure, a cow is deemed to have endometritis ‘dirty’.

-- Whiteside test Cervical mucus: cervical mucus is collected aseptically and mixed with equal volume of 5 % NaOH in a test tube. The mixture is heated up to the boiling point and the intensity of color change is graded as Turbid (Normal), Light yellow (Mild endometritis), Yellow (Moderate endometritis), and Dark yellow (Severe endometritis).

-- Bacteriological examination from collected mucus.

-- Sensitivity test for suitable antibiotics.

- Prognosis of endometritis depends largely on

-- Duration of the disease,

-- Severity,

-- Extension of the lesion.

-- Kind of microorganism.

-- Prognosis is bad in C. pyogenes or E.coli.

- Treatment of endometritis:

1- Evacuation of the uterine contents by induction of estrous to dilate the cervix:

- Cervix is opened by the I.M. injection of either by PGF2α, 25 mg, or Stilbesterol 30-50 mg.

- If the uterus contains dry pus, it will be liquefied by flushing the uterus with sod bicarbonate (3%) warmed solution then gentle massage to help in the evacuation.

2- Intra-uterine application of antibiotics. Several antimicrobial agents are absorbed from the uterus (tetracycline, penicillin, ampicillin and gentamicin). Cephapirin benzathine (500 mg, intrauterine, once; second treatment may be required in 7–14 days if clinical signs persist). 2-3 gm or sulfonamides repeated every 3 days for at least three successive treatments.

When appropriate, administer prostaglandin then administer intrauterine cephalosporin 4-6 days later. All treated cows require re-examination and possibly retreatment at 14-day intervals. Cows that fail to respond to these treatments have a poor prognosis regarding future fertility.

3- 2.0% intrauterine povidone-iodine intrauterine infusion (50-100 ml) seems to be a better option in treating severe clinical endometritis in dairy cows and in those who recover immediately from pyometra

4- Because intrauterine use of antiseptics may suppress the uterine defense mechanisms like phagocytosis, the use of intra uterine infusions in the postpartum cow is not recommended. Lugol’s iodine application must be given after rectal examination and be sure that the uterus returns to normal clinical condition.

5- Autologous plasma: Collect about 100 ml of blood from the estrus animal and separate the plasma. Administer 50 ml of plasma through intrauterine route on days 1, 2 and 3 of estrus.

6- Caslick operation or suturing the vagina in case of pneumo-vagina is recommended.

- The prophylactic measurements:

-- Good balanced ration.

-- Hygienic birth and birth help.

-- Prophylactic antibiotic after birth.

-- Competing infectious disease.

-- The animal never be mated or inseminated on the first two or three heats after recovery.

-- Sometimes a dose of antibiotics or Lugol’s solution is given 15-30 minutes after insemination.

2-Sclerotic metritis:

- The endometrium and caruncles are destroyed.

- Severe chronic metritis.

- The endometrium is converted into a thick dense layer of connective tissue with foci of infection and purulent exudation into the uterine cavity.

- On the rectal examination:

-- The uterus is felt cartilaginous, very hard in texture or dense fibers, enlarged than normal size

-- Chronic exudates may be extruded from the uterus through a thickened indurated cervix.

-- Embedded CL in the ovary.

- The animal shows signs of:

-- Repeat breeding in the early stage,

-- Pyometra and anestrum lately.

- The animal is sterile and being slaughtered.

3- Perimetritis and Parametritis

- Inflammation of the outer coat of the uterus.

- Adhesions between the uterus and broad ligaments.

- The sequence of septic metritis:

-- Following perforation of the uterine wall with a catheter during irrigation of the uterus with irritant material.

-- Rough manipulation of the genitalia during rectal examination.

-- Diffuse peritonitis or tuberculosis.

-- Excessive bleeding after manual removal of CL or cyst.

- The lesion may vary from a few to large adhesion between the uterus, broad ligaments and the other structures.

- The adhesion may be diffuse or localized.

- In some cases, abscess may be found

- In acute case, symptoms are:

-- Anorexia, arched back, fever and tenesmus.

-- Pain at the time of urination or defection.

-- Rectal examination shows signs of pain.

- If the symptoms of acute stage pass without death of the animal, adhesion occurs and become chronic.

- Areas of infection become capsulated and abscesses are formed and can be felt on rectal examination.

- Prognosis varies with the severity of the condition.

-- Slight adhesion causes no disturbances and sometimes can be broken by the hand through the rectum.

-- In severe extensive adhesion, prognosis is unfavorable especially if the ovaries and oviducts are involved.

-- Treatment by antibiotics and sulfonamides may be useful

4- Abscess of the uterine wall:

- It is occasionally observed in the cow.

- It is usually round oval in shape and tense.

- It occurs frequently as a consequence to:

-- Severe metritis,

-- Improper removal of retained placenta,

-- Improper use of pipettes or instruments.

- Rectally, the abscesses are easily palpated.

- They should be differentiated from tumors, cysts or hematoma.

- The general health of the animal is disturbed.

- The case may be fatal if the infection is extended and causes peritonitis.

- For treatment, systemic antibiotic is good value in early stage.

5- Tumors of the uterus:

- They are rare in the cow.

- Mostly benign and occasionally malignant.

- leiomyoma; fibroma; lipoma; adeno-carcinoma, and leucosis in cattle.

- Rectally, the tumor should be palpated easily.

- The animal should be discarded from breeding.

D) Pathological affections of the cervix:

- Cervicitis:

- Inflammation of the cervix.

- It is commonly associated with endometritis, vaginitis, and Pneumo-vagina in cows.

- It follows:

-- Abnormal parturition and abortion,

-- The unhygienic birth help,

-- Polluted vagino-scope or inseminating pipette,

-- Trauma of the cervix by introduction of a catheter,

-- Purulent vaginitis or endometritis.

-- Prolapse of the cervical ring (cervical ectropion) in old cows.

- The animal is a repeat breeder.

- Vaginal examination reveals

-- The cervix is edematous and swollen,

-- The cervical mucosa is red to dark purple.

-- Mucopurulent exudates may be seen.

-- In severe cervicitis, endometritis occurs.

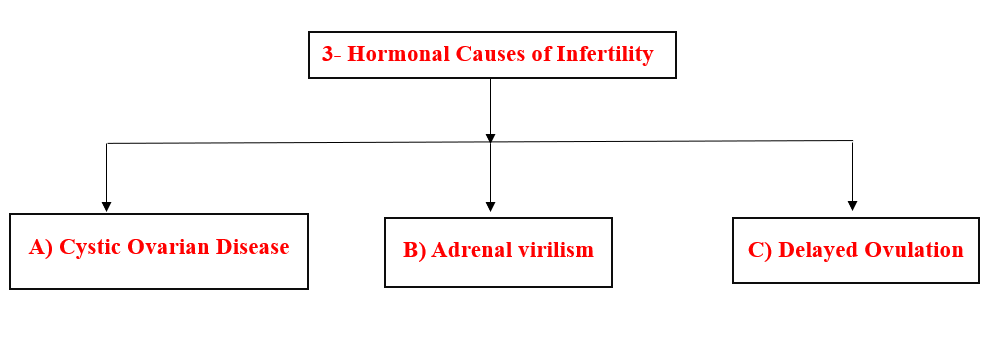

3- Hormonal Causes of Infertility

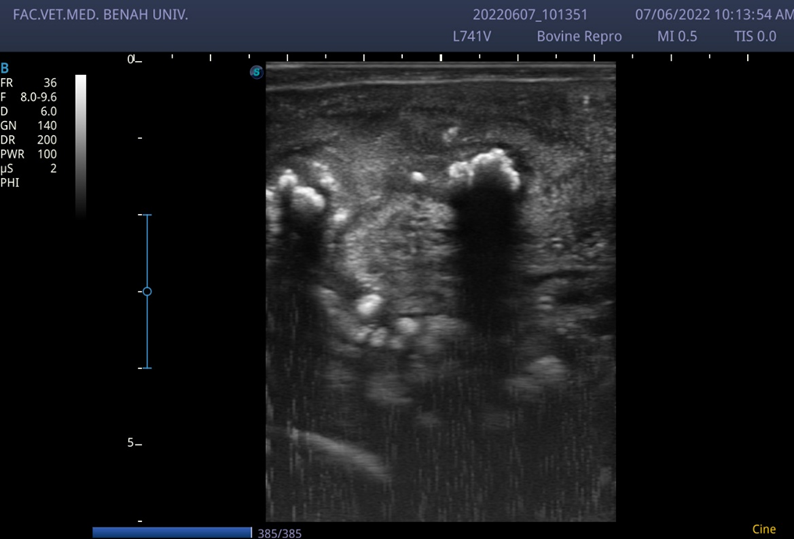

A) Cystic Ovarian Disease (COD)

- Causes of cystic ovarian disease:

- The actual mechanism leading to the development of cystic ovaries is unknown.

- Hereditary predisposition should put in mind.

It is probably due to:

-- Deficiency of LH released prior to time of ovulation.

-- Imbalance between FSH and LH

-- Lack of GnRH from the hypothalamus.

-- High level of LTH in high milk producing animal.

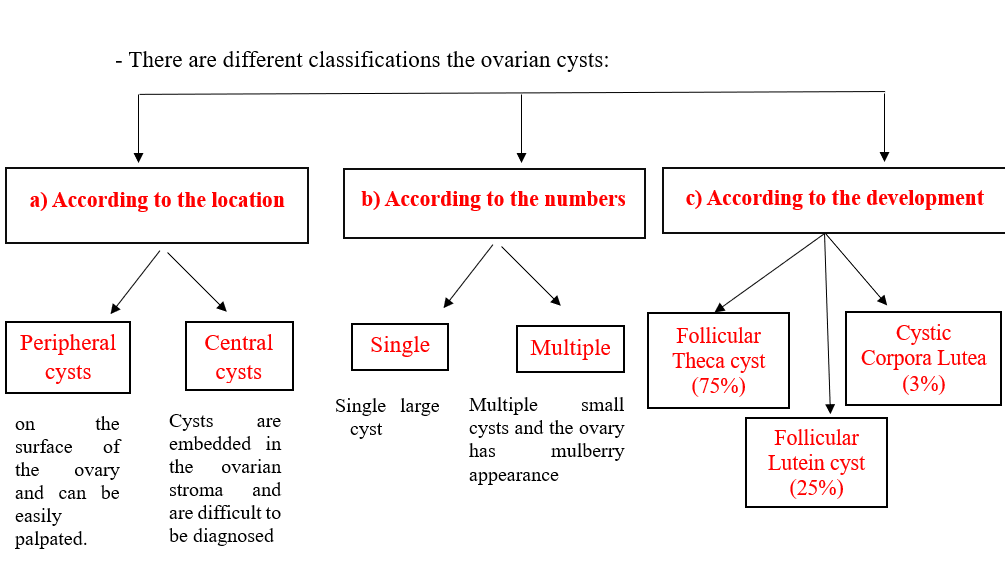

- Diagnose cystic ovarian disease:

- History of high milking animals of 4–8-year-old, within 3–8 weeks of parturition.

- Symptoms vary from signs of nymphomania with frequent irregular or continuous estrus to anestrum according to type of the cyst present in the ovary. The sexual behavior of the animal shows more bull-like, pawing the ground, bellowing and riding other females. Relaxation of the vulva, perineum, and the large pelvic ligaments, which causes the tail head to be elevated (sterility hump) can occur in chronic cases.

- In rectal examination, ovaries generally are enlarged and rounded; however, their size varies by the number and size of the cysts. Their surface is smooth, elevated, and blister-like. In one or both ovaries there will be

-- Enlarged follicles 2-8 cm in diameter and 1-5 in number.

-- Small cysts in very large numbers

-- Thickened and edematous myometrium with normal size.

- Progetsrone hormone assay: Serum progesterone concentrations can be used to classify luteal (> 0.5 ng/ml) or follicular (≤ 0.5 ng/ml) cysts.

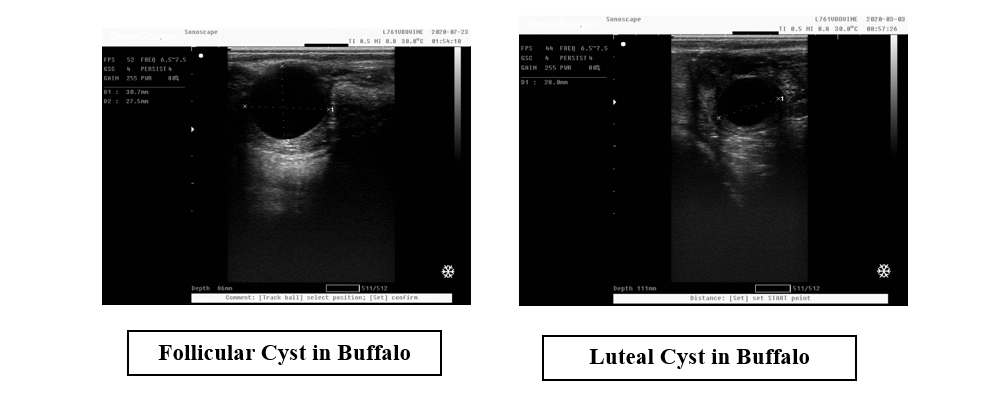

- In ultrasound examination: ultrasound technology is used the accuracy of a correct diagnosis of cyst type was 74% for follicular cysts and almost 90% for luteal cysts. Follicular cysts typically have a thin wall (≤3 mm) whereas luteal cysts typically have a thicker and more echogenic wall (≥3 mm). The follicular fluid is often hypoechoic in follicular cysts, whereas with luteal cysts echogenic strands may be present creating a cobweb-like appearance.

- The vaginal examination reveals that the estrus mucus is opaquer.

- Complications of the ovarian cysts are:

-- Accumulation of abnormal discharge in the uterus.

-- Atrophy of the endometrium after cystic hyperplasia

-- Fragility of bones and their liability for fractures

-- Sterility hump.

- Treatment of cystic ovarian disease:

- The earlier the cystic ovaries are diagnosed and treated, the better is prognosis.

- Large cysts in small numbers tend to respond more readily to treatment than multiple cysts.

- Cystic ovary disease may be refractory to initial treatment.

- Manual rupture of cysts is one method of treating cystic ovary disease; however, the potential danger of traumatizing the ovary and causing hemorrhage with subsequent local adhesions should not be overlooked.

- Medical treatment is directed towards luteinization of the cysts so that the luteal tissue is formed, regressed and the normal cycle is returned.

- Some cysts respond readily to treatment with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) at dose of 5000 – 10000 IU.

- Treatment with GnRH (Gonadorelin) at a dose of 100 mcg is effective and less antigenic than treatment with hCG, which may become less effective on subsequent treatments because of the immune response. To hasten the onset of the first estrus after treatment, prostaglandin F2alpha products can be administered 7-10 days after hCG or GnRH.

- The epidural administration of GnRH analogue (e.g., buserelin at a dose of 10 μg) promotes the remission of follicular cysts and an improvement of reproductive parameters.

- Ovsynch (consists of administering GnRH, then the prostaglandin 7 days later, then a second dose of GnRH 48 hours later) have been successfully used to treat cows with cystic ovaries..

- Intravaginal progesterone devices may also be used to treat cystic ovary disease as progesterone upregulates luteinizing hormone receptors before device removal and luteinizing hormone surge.

- Serial ultrasonography guided aspiration of the cystic fluid may provide benefit by removing physiologically active hormones.

B) Adrenal virilism

- The adrenal cortex of the female secretes a large amount of androgens due to lesions occurring in the adrenal cortex (tumor or hyperplasia) or the hypothalamus.

- In adrenal hyperplasia, cortisol precursors accumulate and are shunted into the production of androgens.

- Excessive sexual desire toward the masculine direction (virilization).

- The clinical symptoms correlate to:

-- The age of the animal

-- The stage of lactation.

- Heifers show enlargement of the clitoris and under development of the sexual organs.

- Old cows become fattened with cessation of sexual desire.

- The ovaries are often small or even enlarged.

- The uterus is under developed in heifers and is normal in cows.

- The treatment in such case is not useful.

C) Delayed ovulation

- An internal prolonged estrus appears in 10 % of cows.

- The external symptoms of estrus are normal.

- History of poor conception rates accompanied by prolonged estrus may indicate that delayed ovulation takes place or that the follicle fails to ovulate.

- Rectally, there is no ovulation within the normal time (10 –18 hours after end of heat).

- Ovulation occurs 24 –72 hours after heat and about 50% of cows give normal ova.

- Conception after mating or A.I. is reduced due to:

- Aging of the oocyte within the follicle

- Sperm aging

- Changes in the oviduct environment

- The animal shows signs of repeated breeding.

Treatment:

-- Apply a second insemination 72 h after heat.

-- Inject LH 5000 IU or GnRH (100 µg) for cattle at the time of AI or up to six hours beforehand

- Don't try to squeeze the G F.

4- Environmental Causes of Infertility

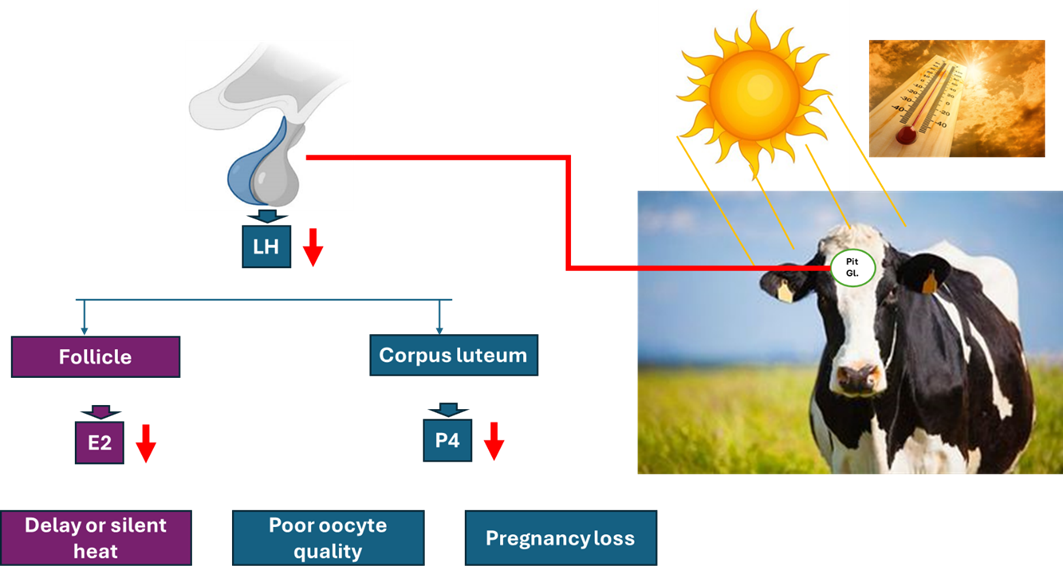

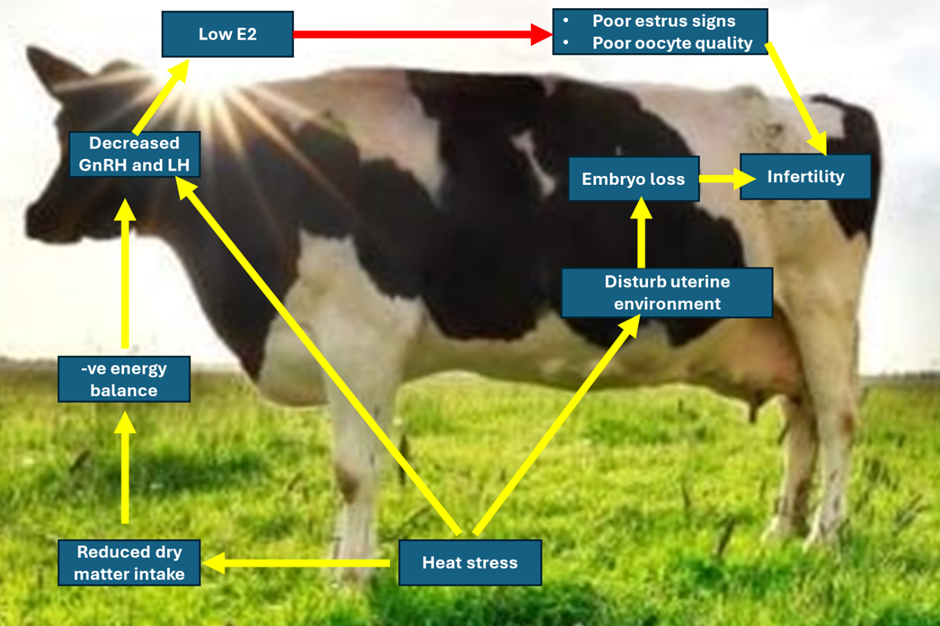

A) Effect of heat stress

- All cattle are at risk on becoming hyperthermia, and the problem is greater on lactating dairy cattle populations.

- The ability to detect estrus declines during periods of heat stress due to:

-- A reduction in the duration of estrous behavior.

-- Reduced locomotors activity.

-- Reduce peripheral concentrations of estradiol-17B,

-- Decrease gonadotropin responses to injection of GnRH in cows with low circulating levels of estradiol-17B

- Heat is the major stressful environmental factor due to:

-- lowered conception rates in the summer.

-- Disrupted ovulation or early pregnancy.

--Altered the normal embryonic development.

- Fertilization failure has been associated with heat stress due to:

-- Effects on the oocyte during follicular development,

-- Effects follicular growth and dominance,

-- Alters the quality of the oocyte.

- Embryos become more resistant to effects of heat stress as pregnancy proceeds due to:

-- Greater cellular resistance to elevated temperatures.

-- Heat-shock protein synthesis in embryos,

-- Other biochemical changes may also be important.

- Hyperthermia disrupts endometrial function through

-- The inductions of endometrial synthesis of two heat shock proteins (HSP-90 and HSP-70) that are the components of the progesterone receptor complex. In addition, the increased synthesis of HSP-70 and HSP-90 in endometrium inhibits endometrial responsiveness to progesterone.

-- It reduces secretion of the anti-luteolytic hormone, Interferone-7 in conceptus by day 17.

-- Increased release of PGF2∞ and PGE2 from the endometrium.

-- Increased uterine production of PGF2∞in response to oxytocin.

- Abortion caused by heat –stress is rare,

- Placental function is influenced by heat stress in the last third of pregnancy during the summer or experimental heat stress, through:

-- Reduced secretion of placental estrone-sulfate hormone.

-- Reduced placental size and calf birth weight.

-- Reduced blood flow to the placenta.

-- Reduced subsequent milk yield.

The effect of Heat stress on reproduction can be prevented by:

1- Increase estrous detection in summer ovulation through the application of estrus synchronization protocols

2- Cooling cows around the time of anticipated estrus might also increase estrous detection.

3- Altering the environment to reduce the magnitude of heat stress improves fertility in Lactating cows.

4- Reproductive biotechnology can eliminate infertility caused by heat stress:

- By A.I., semen collected in cold environments can be stored in a frozen state until later use in hot weather.

- By E.T., embryos that develop to the blastocyst stage with acceptable morphologic characteristics are transferred. Embryos produced by super-ovulation are more likely to survive in heat-stressed recipients than are embryos produced by in-vitro fertilization.

How can you manage a cow in heat stress?

1. Provide shade. The sun's radiant energy adds to the heat load. However, don't cut out ventilation using an enclosed building to provide shade.

2. Control horn flies. Flies cause the cows to "bunch-up".

3. Don't let dry cows to lose weight. If more ration energy is needed, it is probably better to feed higher quality forages than more grain or supplementing fat particularly for far-off dry cows.

4. Don't feed excessive protein (>12-13%). Metabolizing the extra protein adds to the heat load.

5. Consider supplemental cooling especially around calving time.

6. Don't eliminate salt. Sodium and potassium add to a positive cation: anion balance which is undesirable ahead of calving and salt (sodium) has been implicated with udder edema. However, the cow's need for these cations increases with heat stress.

B) Photoperiodism

- Exposure to short photoperiods early in the life, until 3 to 5 months of age, hastens puberty.

- Heifers born in autumn attained puberty sooner than those born in Springs.

- In northern Latitudes, the duration of postpartum anestrus is often shorter for cows calving in the summer or Autumn than for cows calving in the winter or spring.

- The long photoperiodism is effective on reproduction through:

-- Increase conception rates during winter by light supplementation.

-- Increase sperm motility and decrease sperm abnormality in bulls.

-- Reduce the interval to uterine involution.

- At the level of the hypothalamus-pituitary axis:

-- Secretion of LH early in life was greater for heifers born in September than those born in March.

-- Supplemental lighting in the winter increased the magnitude of estradiol-induced LH secretion.

- As in seasonally breeding species, the secretion of melatonin in cattle exhibits a diurnal pattern; the highest concentrations occur during darkness.

C) Nutrition

1- Energy intake:

- The optimal age for Holstein heifers at first calving for total life time production was between 23 and 24 months of age.

-To achieve an average age at first calving of 24 months, heifers must reach puberty by 8 to 9 months of age.

- An excellent plane of nutrition is critical for heifers to reach puberty and first calving at 9 and 24 months and age, respectively.

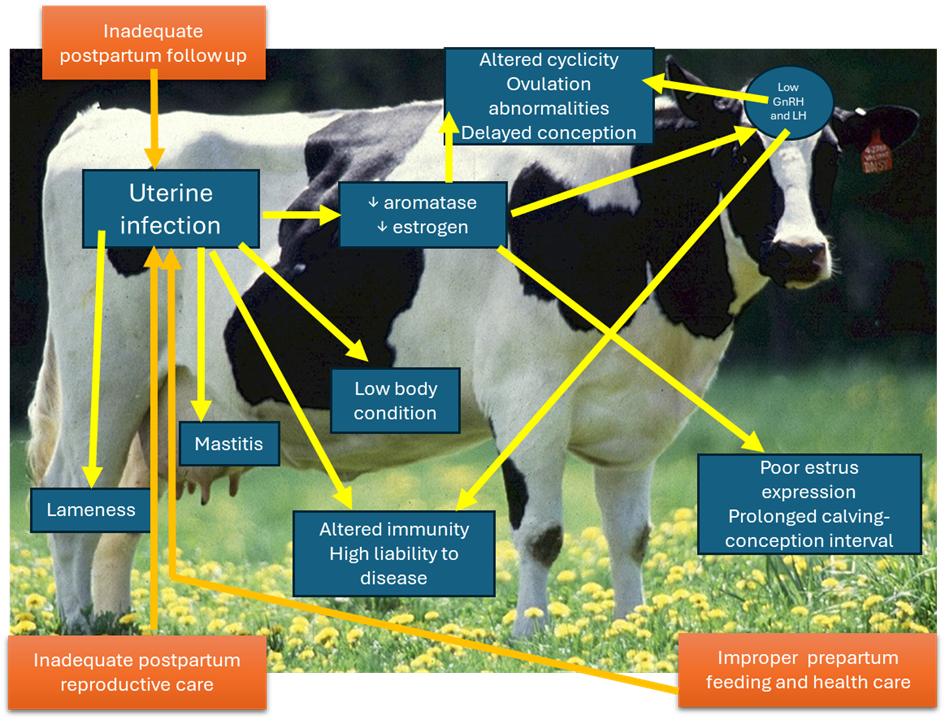

- The nutritional balance of a dairy cow during the periparturient period has a tremendous influence on fertility and reproductive efficiency.

- Negative energy balance (NEB) is the result of increasing milk energy secreted (MES) and maintenance energy (ME) oven the energy intake (EI) as expressed by the equation: NEB = EI – (MES + ME).

- Negative energy balance can increase the period of postpartum anestrus and decrease fertility at first and subsequent inseminations depending on the severity of the imbalance.

- In cattle, under severe negative energy balance, the secretion of LH is inhibited. Disrupted or decreased LH secretion slows the growth and development of the follicle which delay ovulation.

- Cows in negative energy balance have reduced levels of insulin–like growth factor –1 (1GF–1) which amplifies the effect of LH on the ovary through potentiating the signaling mechanism for LH.

- Cows that had first ovulation before 40 days postpartum had the highest concentrations of plasma IGF-1. Therefore, the interval to first ovulation is controlled primarily by energy balance.

- In addition to decreased interval to first ovulation, improved energy balance during early lactation can decrease the incidence of other ovarian diseases. For example, cystic ovaries are most prevalent in high producing cows that are in negative energy balance.

- Energy status at the time of breeding can also affect reproduction. Cows that loss weight at the time of breeding have lower fertility in association with decreased progesterone secretion by the corpus luteum. Inadequate uterine function may be related to lower progesterone concentration in cows in poor body condition. Furthermore, progesterone release in response to LH is severely diminished in the absence of IGF-1.

- Insulin can be used for induction of estrus in animals. The recommended dose is 0.25 IU/kg body weight subcutaneously for 3–5 days. The treatment of true anestrus buffaloes is satisfactory when single intramuscular injection of PMSG (500 IU) was combined with subcutaneous injections of insulin @ 0.25IU/Kg body weight for five consecutive days.

2- Proteins:

- A severe urea nitrogen level greater than 20 mg/dl, resulted in a lower conception rate.

- Cows fed 19 to 21 percent crude protein diets had higher blood urea nitrogen (21.3 vs 13.8mg /dl) and lower conception rate (62 vs 48 %) compared with cows fed diets containing 15 to 16 percent crude protein.

- Elevated blood levels of ammonia or urea or both could alter secretions produced in the reproductive tract itself and alter viability of the ovum, sperm or embryo. In addition, the hormonal balance required for normal function might also be involved.

-. Excess ammonia absorbed from the rumen of cows fed high– rumen degradable protein or soluble crude protein diets could down – regulate a hormonal or metabolic signal to the ovary.

3- Minerals and vitamins:

- Cows fed high calcium and vitamin- D diets prepartum had more rapid uterine involution, fewer days to first service, and fewer days open.

- Parturient hypocalcemia significantly increases the rate of dystocia and retained placenta. Hypocalcemia could reduce normal uterine function.

- Dairy heifers suffering from phosphorus deficiency have high rates of infertility as measured by services per conception. Increasing phosphorus in the diet returns blood levels to normal and fertility is improved. A minimum Ca : P ratio of 1.5 : 1.0 and minimum daily intake phosphorus of 30g was suggested.

- Selenium and vitamin-E are the two most often considered for a herd suffering from reproductive problems. Supplemental selenium and vitamin-E 30 days prepartum reduced the incidence of retained placenta.

- Copper supplementation increases fertility when combined with increased phosphorus.

- Manganese has also been shown to influence reproduction. The conception rate was improved by feeding supplemental manganese.

- Zinc is recognized as an essential nutrient required for normal growth. Zinc deficiency increases the length of labor and bleeding time in the rat and ewe. Zinc is important for testosterone biosynthesis and spermatogenesis.

- Beta–carotene has also been investigated as a nutrient having special requirements for reproduction. High levels of carotene were estimated in the blood, corpus luteum and follicular fluid, but effects on ovarian functions were not described.

- The most common trace mineral deficiencies in beef cow systems are copper and zinc. Supplementation of these minerals is needed. Increased amounts of both will be needed when feeding low quality forages. Copper needs will vary based on molybdenum and sulfur intake.

- Supplemental manganese may be needed if silage is fed; especially if the silage is contaminated with soil.

- Phosphorus is the most expensive mineral to supplement. Producers should consider the contribution of the forage, and any concentrates (grains/co-products) fed to determine how much, if any, supplemental phosphorus is needed.

- The less time cows spend grazing green forage, the greater their supplemental vitamin A needs.

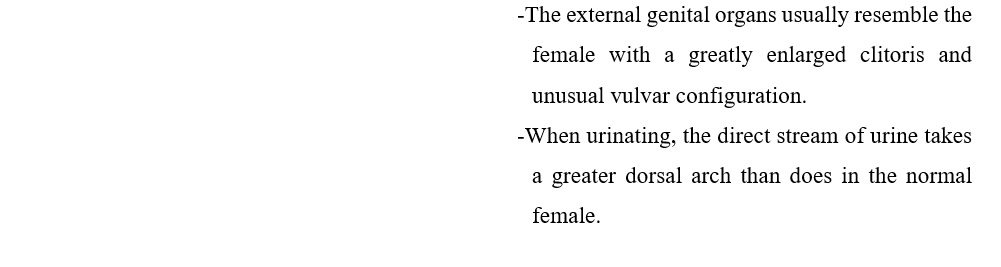

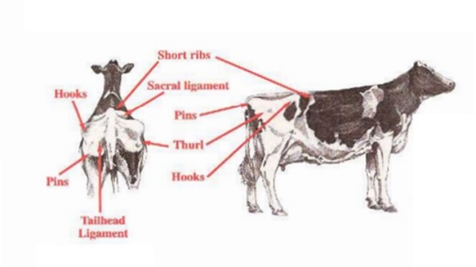

- Body Condition Score (BCS) in Cattle

Body condition refers to the relative amount of subcutaneous body fat or energy reserve. It identifies the degree of preparedness of animals to meet the specific production task expected, whether quantity and/or quality. It is a visual assessment of the animal’s state of fatness and is expressed as a numerical score typically ranging from 1 – 5 (although some species use a range of 1 – 9) with 1 indicating very poor condition (i.e. emaciated) and 5 representing excessive fat deposition (i.e. obese) Often scores will be further subdivided into quarters, or tenths or +/- to provide greater precision.

Cattle Body Condition Scoring

It is an important management tool for maximizing milk production and reproductive efficiency while reducing the incidence of metabolic and other peripartum diseases in dairy cows. Most body condition scoring (BCS) systems in dairy cattle use the 5-point scoring system (Wildman et. al.1982) with 0.25 increments. Over-conditioning (BCS>4.0) at the time of calving results in reduced feed intake and increased incidence of peripartum problems. While the under-conditioning at calving (BCS) often results in less peak milk yield and lower milk for the entire lactation. The excessive loss of body condition in early lactation has been shown to reduce reproductive efficiency.

A flow chart system has been developed as an organized process for BCS dairy cows (Ferguson et al., 1994). This system concentrates its accuracy toward the mid scores (2.5 to 4.0) as the mid-range BCS are the most critical for making management decisions. The flow chart directs the scorer to view certain anatomical sites of the loin and pelvic areas.

Steps of BCS flow chart:

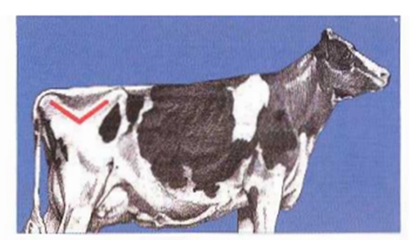

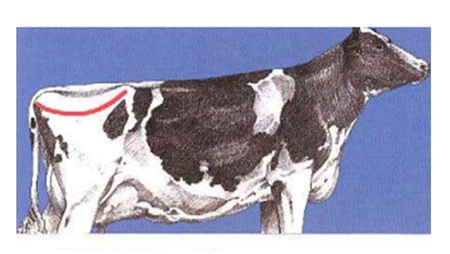

1- Determine if the line from the hook bone, to the Thuri, to the pin bone is angular (V) (BCS ≤ 3) or crescent (U) (BCS ≥ 3.25).

2- If uncertain of the V or U proceed to the next step. View the cow from the rear. Observe the amount of padding over the hook and pin bones and the prominence of the tailhead and sacral ligaments.

Grades of BCS in cattle (Huţu & Onan, 2019)

|

BCS |

Description |

|

1 |

Cows in poor physiological condition; no palpable fat deposit. |

|

2 |

Spinous processes of loins are individually visible; no fat in stifle region; Thurles concave; tail-head depression deep. |

|

2.5 |

Thin cows; insufficient fat deposits; discrete spinous processes; very little flank fullness; Thurles concave, relatively deep tail-head depression; concave loin shape with minimal fat deposition. |

|

3 |

Well-fed cows; spinous processes still discretely visible; flanks slightly concave; tail-head depression smooth. |

|

3.5 |

Defines the ideal condition of cows during the 2nd third of lactation; if in the final third of lactation, the cow still needs to develop the condition. Spinous processes are no longer individually visible (the top of the back is straight); flanks are nearly smooth; thurls are flat; the tailhead cavity is filled with fat tissue. |

|

4 |

Identifies condition goal for cows at calving (too much condition for other production stages); spinous processes not visible--flat line profile; flanks full; thurls flat; tailhead cavity bulging with rolls of fat around tailhead itself. |

|

5 |

Overfat conditions leave cows prone to metabolic disorders; spinous processes are set deep within a fat layer; bulging flanks, bulging thurls; bulging fat in tailhead depression and around the tailhead base. |

- Summary of cattle Infertility Cases Treatment & Interference

|

Case |

Diagnosis |

Interference |

|

|

A- Congenital anomalies |

|||

|

1. Unilateral Ovarian Aplasia |

The genital tract is developed with the absence of one ovary |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

2. Bilateral Ovarian Aplasia |

The genital tract is underdeveloped Steer-like appearance |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

3. Ovarian Hypoplasia |

The ovary is small, thin, firm in consistency, and difficult to be find during examination |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

4. Hermaphroditism |

two sex organs are present in one animal |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

5. Freemartinism |

the ovaries and the uterus are rudimentary and cannot be palpated. Steer-like appearance |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

6. Aplasia of fallopian tube

|

The uterus and ovary are normally present. animal shows estrus. |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

7. Occlusion of fallopian tube |

The uterus and ovary are normally present. animal shows estrus. Cystic dilatation of the fallopian tube |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

8. White Heifer Disease

|

- Absence of either the cranial part of the vagina, the cervix or the uterine body. - presence of hymeneal constriction |

- Discard the animal from the breeding in the 1st 2 classes. - Surgical removal of hymeneal constriction in the 3rd class |

|

|

9. False double cervix |

a band of tissue caudal to the external os of the cervix. |

- Surgical incision of the band |

|

|

10. True double cervix |

The band of tissue separating the two openings extend for a short way into the caudal part of the cervical canal. |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

11. Occlusion of the cervical canal |

failure of canalization of the Mullerian ducts at the cervical region |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

B- Pathological cases |

|||

|

1. Oophoritis |

Adhesion of the ovary with the ovarian bursa results in pressure atrophy on the ovary and anestrus. |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

2. Para-ovarian cysts |

Cystic dilatation of the remnants of the Wolffian ducts neighboring to the ovary round or oval in shape, does not interfere with the fertility |

Surgical removal of the cyst |

|

|

3. Granulosa cell tumor |

Large size structure with an irregular surface and fleshy texture on the surface of the ovary. The animal shows signs of nymphomania |

Ovariectomy of the affected ovary |

|

|

4. Ovarian atrophy |

The animal is sterile due to loss of ovarian activities |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

5. Endosalpingitis |

The animal becomes a repeat breeder |

Systemic treatment with sexual rest may be effective |

|

|

6. Interstitial salpingitis |

The fallopian tube is pencil-like, very hard, and palpated. The animal becomes a repeat breeder |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

7. Hydrosalpinx |

FT is palpated The animal becomes a repeat breeder |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

8. Polysalpinx |

FT is palpated The animal becomes a repeat breeder |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

9. Endometritis |

- Heterogenous echogenicity of the uterus by ultrasonography. - Enlarged uterus with thick wall and thick endometrium - Pus accumulation in the uterus and the uterus becomes doughy in consistency. - Animal my discharge pus |

- Evacuation of the uterus from the pus using PGF2α. - Pus Liquefaction using Sod. Bicarbonate 3%. - Intrauterine antibiotic treatment. - Sexual rest foe 2-3 cycles |

|

|

10. Sclerotic metritis |

The uterus is felt cartilaginous, very hard in texture or dense fibers, enlarged than normal size |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

11. Peri- and parametritis |

Adhesions between the uterus and broad ligaments |

Treatment by antibiotics and sulfonamides may be useful |

|

|

12. Abscess of the uterine wall |

round oval tense structure in the wall of the uterus |

Systemic antibiotic is good value in the early stage |

|

|

13. Tumors of the uterus |

Rectal palpation of the tumor |

Discard the animal from the breeding |

|

|

14. Cervicitis |

- The cervix is edematous and swollen - The cervical mucosa is red to dark purple. - The animal becomes a repeat breeder |

Treatment by antibiotics and sulfonamides may be useful |

|

|

3- Hormonal Cases |

|||

|

1. Cystic Ovarian Disease |

- Presence of large cyst with thick or thin walls on one or both ovaries. - Animal show nymphomania and or anestrum |

Treatment with the cyst with GnRH followed by PGF2α.

|

|

|

2. Adrenal virilism |

Heifers show enlargement of the clitoris and underdeveloped sexual organs |

Discard from the breeding |

|

|

3. Delayed Ovulation |

Normal estrus with ovulation occurs 24 –72 hours after heat |

- Apply a second insemination 72 h after heat. - Inject LH 5000 IU. |

|

- References:

[1] Arthur GH, Noakes DE, Pearson H (1992) Arthur’s veterinary reproduction and obstetrics. (6th edn), Great Britain, pp: 352-366.

[2] Berg DK, van Leeuwen J, Beaumont S, Berg M, Pfeffer PL (2010) Embryo loss in cattle between day 7 and 16 of pregnancy. Theriogenology 73: 250-260.

[3] Butler WR (2000) Nutritional interactions with reproductive performance in dairy cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 60-61: 449-457.

[4] Charlton H1 (2008) Hypothalamic control of anterior pituitary function: A history. J Neuroendocrinol 20: 641-646.

[5] Córdova A, Leal A, Murillo A, José Manuel, Claudia Irais (2002) Causa de infertilidad en ganado bovino. Medicina Veterinaria 19(9): 112-124.

[6] Dalton JC, Nadir S, Bame JH, Noftsinger M, Nebel RL, et al. (2001) Effect of time of insemination on number of accessory sperm, fertilization rate, and embryo quality in nonlactating dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 84(11): 2413-2418.

[7] Diskin MG, Morris DG (2008) Embryonic and early foetal losses in cattle and other ruminants. Reprod Domest Anim 43: 2260-267.

[8] Diskin MG, Murphy JJ, Sreenan JM (2006) Embryo survival in dairy cows managed under pastoral conditions. Ani Reprod Sci 96: 297-311.

[9] Dohmen MJW, Lohuis JACM, Gy H, Nagy P, Gacs M The relationship between bacteriology and clinical findings in cows with sub-acute/chronic endometritis. Theriogenology. (1995) 43:1379–88. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(95)00123-P

[10] El-Azab MA, Whitmore HL, Kakoma I, Brodie BO, M (1988) cKenna DJ, Gustafsson BK. Evaluation of the uterine environment in experimental and spontaneous bovine metritis. Theriogenology. 29:1327–34. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(88)90012-X

[11] Evans JP (2002) The molecular basis of sperm-oocyte membrane interactions during mammalian fertilization. Hum Reprod Update. 8:297–311. doi: 10.1093/ humupd/8.4.297

[12] Farin PW, Youngquist RS, Parfet JR, Garverick HA (1992) Diagnosis of luteal and follicular ovarian cysts by palpation per rectum and linear-array ultrasonography in dairy cows. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 200(8):1085-1089.

[13] Fourichon, C, Seegers H, Malher X (2000) Effect of Disease in the Dairy Cow: Meta-Analysis. Theriogenology 53(9): 1729-1759.

[14] Hafez ESE (1993) Reproduction in farm animals. (6th ed), Philadelphia, pp: 59-104.

[15] Krishnan BB, Kumar H, Mehrotra S, Singh SK, Goswami TK, Khan FA, et al. (2015) Effect of leukotriene B4 and oyster glycogen in resolving subclinical endometritis in repeat breeding crossbred cows. Indian J Animal Res. 49:218–22. doi: 10.5958/0976-0555.2015.00112.0

[16] Kübar H, Jalakas M. (2002) Pathological changes in the reproductive organs of cows and heifers culled because of infertility. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 49(7):365-72. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0442.2002.00459.x. PMID: 12440792.

[17] Kumar PR, Singh SK, Kharche SD, Govindaraju CS, Behera BK, Shukla SN, Kumar H, Agarwal SK (2014). Anestrus in cattle and buffalo: Indian perspective. Advances in Animal and Veterinary Science. 2(3):124-138.

[18] Landau S, Braw Tal R, Kaim M, Bor A, Bruckental I (2000) Preovulatory follicular status and diet affect the insulin and glucose content of follicles in high-yielding dairy cows. Anim Reprod Sci 64(3-4): 181-197.

[19] McEntee K (1990): Reproductive pathology of domestic mammals. 1st Edition. eBook ISBN: 9780323138048.

[20] Metwelly KK (2001) Postpartum anoestrus in buffalo and cows: Causes and treatment. Proceedings of the sixth scientific congress Egyptian society for cattle diseases, Egypt, Assuit University, pp: 259-267.

[21] Millar RP, Lu ZL, Pawson AJ, Flanagan CA, Morgan K et al. (2004) Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Endocr Rev 25: 235-75.

[22] Morrow DA (1970) Diagnosis and prevention of infertility in cattle. J Dairy Sci. 53(7):961-969.

[23] Nebel RL, Saacke RG (2001) Fertilization Rate, and Embryo Quality in Nonlactating Dairy Cattle. J Dairy Sci 84:1277-1293.

[24] Osawa T (2021). Predisposing factors, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of persistent endometritis in postpartum cows. J Reprod Dev. 67(5):291-299.

[25] Parkinson TJ (2019) Infertility in the cow due to functional and management deficiencies. Veter Reprod Obstetrics WB Saunders. 2:361–407. doi: 10.1016/ B978-0-7020-7233-8.00022-7

[26] Pascottini OB, Dini P, Hostens M, Ducatelle R, Opsomer G (2015) A novel cytologic sampling technique to diagnose subclinical endometritis and comparison of staining methods for endometrial cytology samples in dairy cows. Theriogenology 84(8):1438-1446.

[27] Pasolini MP, Prete CD, Fabri S, Auletta L (2016) Endometritis and infertility in mares-the challenge in the equine breeding industry-a review. Genital Infect Infert. 285–328. doi: 10.5772/62461

[28] Peters JL, Senger PL, Rosenberg JL, O Connor (1984) Radiographic evaluation of bovine artificial inseminating technique among professional and herdsman-inseminators using .5- and .25-ml French straws. J Anim Sci 59(6): 1671-1683

[29] Sheldon IM, Noakes DE, Rycroft AN, Pfeiffer DU, Dobson H (2002) Influence of uterine bacterial contamination after parturition on ovarian dominant follicle selection and follicle growth and function in cattle. Reproduction. 123:837–45. doi: 10.1530/ rep.0.1230837

[30]

[31] Smith OB, Akinbamijo OO (2000) Micronutrients and reproduction in farm animals. Anim Reprod Sci 60-61: 549-560.

[32] Srivastava SK, Shinde S, Singh SK, Mehrotra S, Verma MR, Singh AK, et al. (2017) Antisperm antibodies in repeat-breeding cows: frequency, detection and validation of threshold levels employing sperm immobilization, sperm agglutination and immunoperoxidase assay. Reprod Domest Anim. 52:195–202. doi: 10.1111/ rda.12877

[33] Studer E (1998) A veterinary perspective on of farm evaluation of nutrition and reproduction. Journal Dairy science 81(3): 872-876.

[34] Vandeplassche M. (1981) New comparative aspects of involution and puerperal metritis in mare, cow and sow. Vet Med. 36:804–7

[35] Veepro H (2002) Problemas en el periodo de parto. Mexico Holstein 33(9): 9-13.

[36] Walsh SW, Williams EJ, Evans AC (2011) A review of the causes of poor fertility in high milk producing dairy cows. Anim Reprod Sci 123: 127-138.

[37] zab MA, Badr A, Shawki G, Medeg SSA (1993) Some microelements profile in ciclie non-breding cow sydrome (repeat breeder). Assiut Veterinary Medical Journal 29(58): 245-253.

[38] Pearson H, England GCW (1993) Veterinary reproduction and obstetrics, Bailliere Tindac: Great Britain 270-278.

[39] Dransfied MBG, Nebel RL, Pearson RE, Warnick LD (1998) Current therapy in theriogenology. 81: 1874.

[40] Peters AR, Ball HJH (1995) Reproduction in dairy cattle. (2nd ed), Black well science ltd, London, UK, pp: 23-61,89-105.

[41] Garverick HA1 (1997) Ovarian follicular cysts in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 80: 995-1004.

[42] Youngquist RS, Threlfall WR (2007) Ovarian follicular cysts: Current therapy in large animal theriogenology, Saunders Elsevier, pp: 379-383.

[43] Vanholder T1, Opsomer G, de Kruif A (2006) Aetiology and pathogenesis of cystic ovarian follicles in dairy cattle: A review. Reprod Nutr Dev 46: 105-119.

[44] Bartolome JA, Thatcher WW, Melendez P, Risco CA, Archbald LF (2005) Strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cysts in dairy cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc 227: 1409-1414.

[45] Henneke, D.R.; Potter, G.D.; Kreider, J.L.; Yeates, B.F. Relationship between condition score, physical measurements and body fat percentage in mares. Equine Vet. J. 1983, 15, 371–372.

[46] Hutu I & Onan G. 2019. Body Condition Scoring. In: Animal Production - practical Exercises, 2nd Ed., Agroprint - Timişoara, RO, 2019.

[47] Ferguson JD, Galligan DT, and Thornsen N. 1994. Principal descriptors of body condition score in Holstein cows. J. DAiry Sci. 77: 2695-2703.

[48] Wildman, EE, GM Jones, PE Wagner, RI Bowman, HF Trout, and TN Lesch, 1982. A dairy cow body condition scoring system and its relationship to selected production variables in high-producing Holstein dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci., 65: 495.