Multiple Sclerosis

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Neurology Guidelines |

| Book: | Multiple Sclerosis |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 10:24 PM |

Description

"last update: 23 Sep. 2024"

- Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the Committee of National Egyptian Guidelines, Ministry of Health and Neurology Scientific Committee for adapting these Guidelines.

Chair of the panel: Hassan Hosni

Scientific group members: Azza Abdlnasser, Ahmed Elbassiouny, Mona Ahmed Nada, Magdy Khalaf, Tarek Rageh, Ahmed Attia, Romany Adly, Mohamed Mahmoud Fouad, Ahmed Fawzi Amin

- Abbreviations

CIS: Clinically Isolated Syndrome

DIS: Dissemination in Space

DIT: Dissemination in Time

DMT: Disease Modifying Therapy

Expanded Disability Status Scale: EDSS

MS: Multiple Sclerosis

PPMS: Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis

RRMS: Relapsing Remittent Multiple Sclerosis

SPMS: Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis

- Glossary

Clinical isolated syndrome (CIS) is defined as a single episode of neurological symptoms suggestive of MS, typically involving the optic nerve, brainstem/cerebellum, spinal cord or cerebral hemisphere, considering that other possible explanations need to be ruled out by a comprehensive work-up.

- Executive Summary

The scope of these guidelines is to provide practical recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of MS based on current scientific evidence.

▶️ Acute MS relapses should be diagnosed when the patient develops symptoms that occur over a minimum of 24 hours and separated from a previous attack by at least 30 days, in the absence of fever or infection. In the radiological domain, the criteria for relapses are defined as an increase in lesion load/size on T2 imaging or gadolinium enhancement of lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the brain or spinal cord.

▶️ It is recommended to treat initially acute MS relapses with a 3–5 day course of intravenous methylprednisolone.

▶️ The diagnosis of relapsing remittent multiple sclerosis (RRMS) should be promptly considered after the patient experiences the first symptoms that may be suggestive of MS relapse, what is termed as clinical isolated syndrome (CIS).

▶️ RRMS should be diagnosed if there is a proof for dissemination in space (DIS) and dissemination in time (DIT). DIS is proved if there is one or more lesion in each of two or more of the four following areas: periventricular, cortical/juxtacortical, infratentorial, and spinal cord, taking into consideration that symptomatic lesions can be used to demonstrate DIS. DIT is proved if there is simultaneous presence of gadolinium enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time, or if a new T2 lesion on follow up MRI irrespective of timing of baseline scan, or the demonstration of cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands in the absence of atypical CSF findings.\

▶️ Neurologists should counsel patients with MS that DMTs are prescribed to reduce relapses and new MRI lesion activity, and should counsel on the importance of adherence to DMT.

▶️ Neurologists must ascertain and incorporate/review preferences in terms of safety, route of administration, accessibility of the drug, efficacy, common adverse effects, and tolerability in the choice of DMT in MS patients.

▶️ Neurologists should monitor the reproductive plans of women with MS and counsel regarding reproductive risks and use of birth control during DMT use in women of childbearing potential who have MS (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

▶️ Neurologists could prescribe highly effective DMTs (such as fingolimod, cladribine, natalizumab, or ocrelizumab) from the beginning for highly active MS patients and aggressive MS patients.

▶️ Neurologists should monitor MRI disease activity from the clinical onset of disease to detect the accumulation of new lesions in order to inform treatment decisions in people with MS using DMTs.

▶️ Neurologists should discuss switching from one DMT to another in MS patients who have been using a DMT long enough for the treatment to take full effect and are adherent to their therapy when they experience 1 or more relapses, 2 or more unequivocally new MRI-detected lesions, or increased disability on examination, over a 1-year period of using a DMT.

▶️ Neurologists should offer siponimod for active SPMS patients evidenced by relapses or imaging-features of inflammatory activity.

▶️ Neurologists should offer ocrelizumab for PPMS patients.

- Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that is characterized by inflammation, demyelination and degenerative changes. MS constitutes the most frequent cause of non-traumatic disability in the young adult population.

Most of the patients have a relapsing course from onset (relapsing remittent MS) that is characterized by relapses and remission of neurological symptoms associated with areas of CNS inflammation, and over the course of two decades more than half of untreated patients transition to a phase of gradual worsening independent of acute attacks (secondary progressive MS). Progressive forms of MS can be present as the initial disease course (primary progressive MS).

The current therapeutic strategy for MS is aimed at reducing the risk of relapses and potentially disability progression. Recently, the growing armamentarium of therapies brings new opportunities for individualized therapy where patients and providers must balance considerations around efficacy, side effects and potential harm in a shared decision process. However, the variety of mechanisms of action, monitoring requirements and risk profiles together with the existing knowledge gaps make individualized medicine a complex task. There is still controversy about the relative efficacy of the drugs available, who should receive therapy and the optimum time to start. The heterogeneity of MS makes it difficult to choose the appropriate drug. Moreover, despite the identification of several prognostic factors, there is no accepted consensus definition that allows physicians to classify patients into high risk and low risk groups in order to prioritize treatment strategies.

➡️Scope and Purpose

This guideline covers the management of MS and its subtypes. This edition includes updated evidence with literature searches completed up to September 2022 and with some major publications since that date also included. This guideline is not intended to overrule regulations or standards concerning the provision of services and should be considered in conjugation with them. In considering and implementing this guideline, users are advised to also consult and follow all appropriate legislation, standards and good practice.

The national guideline for MS clarifies the quality improvement opportunities in the management of MS and to create explicit and actionable recommendations to implement these opportunities in clinical practice. Specifically, the goal is to improve the practice of neurologists as regards the management of relapses and use of Disease Modifying Therapies (DMTs) in the different types of MS.

➡️The target audience

The guideline is intended for all the medical specialists who are likely to diagnose and manage MS especially the neurologists, pharmacists and nurses, and it applies to any setting in which MS would be identified, monitored, or managed.

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

• Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

• Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

• Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later)

• Selecting peer reviewed publications only

• Selecting guidelines written in English language

• Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input

• Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

• Developing organization/authors

• Date of publication, posting, and release

• Country/language of publication

• Date of posting and/or release

• Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. The main guidelines were of the American Academy of Neurology and MENACTRIMS guidelines.

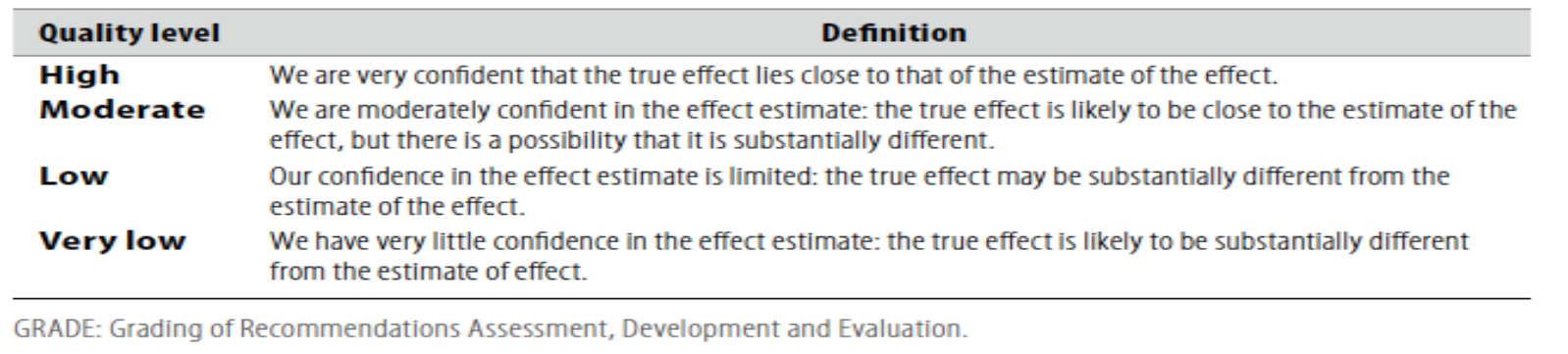

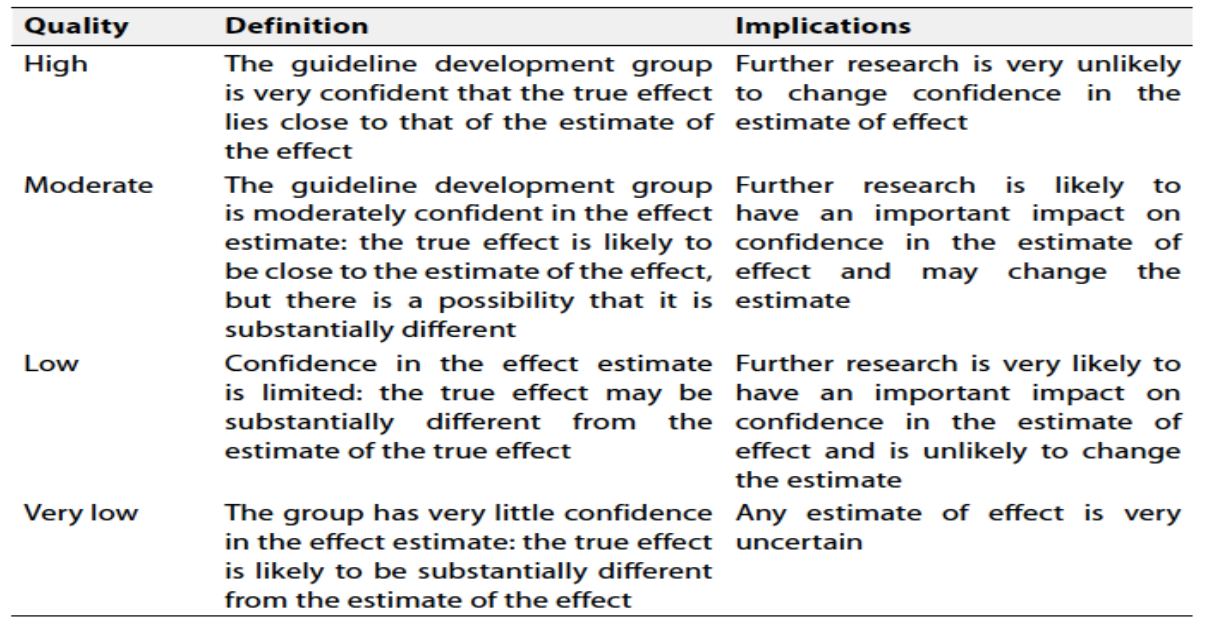

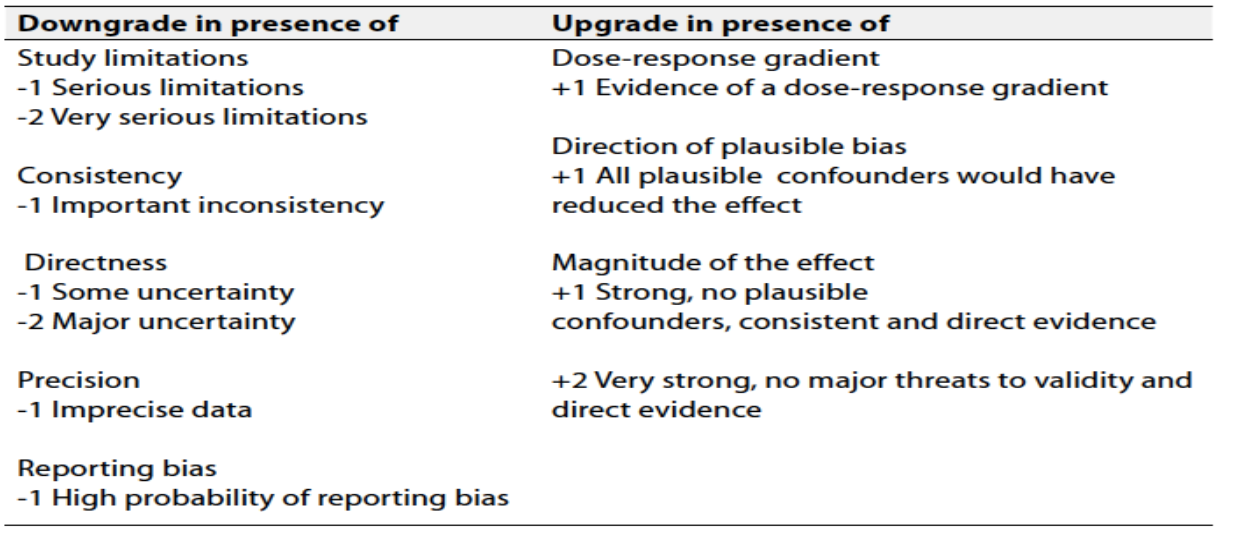

Evidence assessment

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available through the GRC secretariat and on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

Table 1: Quality of evidence in GRADE

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

Table 2: Significance of the four level of evidence

Table 3: Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of Evidence

The strength of the recommendation: The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

Strong recommendations

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

Conditional recommendations

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

When not to make recommendations

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

- Recommendations

1-When to diagnose MS relapse?

Acute MS relapses should be diagnosed when the patient develops symptoms that occur over a minimum of 24 hours and separated from a previous attack by at least 30 days, in the absence of fever or infection. In the radiological domain, the criteria for relapses are defined as an increase in lesion load/size on T2 imaging or gadolinium enhancement of lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the brain or spinal cord (1) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

2- How to treat MS relapses?

It is recommended to treat initially acute MS relapses with a 3–5 day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (2) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

3-When to diagnose Relapsing Remittent Multiple Sclerosis?

The diagnosis of relapsing remittent multiple sclerosis (RRMS) should be promptly considered after the patient experiences the first symptoms that may be suggestive of MS relapse, what is termed as clinical isolated syndrome (CIS) (3) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

3.1 What are the criteria needed to diagnose relapsing remittent multiple sclerosis in patients presenting with typical clinical isolated syndrome?

According to the 2017 McDonald criteria, RRMS should be diagnosed if there is a proof for dissemination in space (DIS) and dissemination in time (DIT). DIS is proved if there is one or more lesion in each of two or more of the four following areas: periventricular, cortical/juxtacortical, infratentorial, and spinal cord, taking into consideration that symptomatic lesions can be used to demonstrate DIS. DIT is proved if there is simultaneous presence of gadolinium enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time, or if a new T2 lesion on follow up MRI irrespective of timing of baseline scan, or the demonstration of cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands in the absence of atypical CSF findings (3) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

3.2 What is the role of MRI in diagnosis of MS?

Brain MRI should be obtained in all patients being considered for an MS diagnosis. Spinal MRI is recommended when the presentation suggests a spinal cord localization, when there is a primary progressive course, or when additional data are needed to increase diagnostic confidence (3) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

3.3 What is the role of CSF in diagnosis of MS?

In patients with typical CIS, fulfillment of MRI criteria for DIS, and no better explanation for the clinical presentation, demonstration of CSF oligoclonal bands (OCBs) allows a diagnosis of MS to be made, even if the MRI findings on the baseline scan do not meet the criteria for DIT and in advance of either a second attack or MRI evidence of a new or active lesion on serial imaging. This recommendation allows the presence of CSF OCBs to substitute for the requirement for fulfilling DIT in this situation (3) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

4-When to diagnose Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis?

We suggest that secondary progressive MS (SPMS) is diagnosed if there is a history of confirmed gradual progression for 3 months at least without preceding relapse, with a minimum Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 4, after an initial RRMS course (4) (conditional recommendation) (moderate quality evidence).

5-When to diagnose Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis?

According to the 2017 McDonald criteria, primary progressive MS (PPMS) should be diagnosed in patients who experience worsening disability for at least one year (based on previous symptoms or ongoing observation), and who exhibit at least two of the following criteria: at least one MS-like lesion in the brain, at least two lesions in the spinal cord, or positive test for oligoclonal bands in the CSF (3) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

6- How to manage patients with Relapsing Remittent Multiple Sclerosis?

Neurologists should offer early treatment with disease modifying therapies (DMTs) in patients with relapsing remitting MS as defined by clinical relapses and/or MRI activity (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence) (5). Please check the annexes for the list of the available DMTs in RRMS.

6.1 Starting DMT: Recommendations

Statement 6.1.1: Neurologists should counsel patients with MS that DMTs are prescribed to reduce relapses and new MRI lesion activity, and should counsel on the importance of adherence to DMT (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

Statement 6.1.2: Neurologists must ascertain and incorporate/review preferences in terms of safety, route of administration, accessibility of the drug, efficacy, common adverse effects, and tolerability in the choice of DMT in MS patients (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

Statement 6.1.3: Neurologists should monitor the reproductive plans of women with MS and counsel regarding reproductive risks and use of birth control during DMT use in women of childbearing potential who have MS (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

Statement 6.1.4: Neurologists could prescribe highly effective DMTs (such as fingolimod, cladribine, natalizumab, or ocrelizumab) from the beginning for highly active MS patients and aggressive MS patients. The choice depends on the patient’s characteristics and comorbidities, drug safety profile, pregnancy issue and accessibility of the drug (7) (conditional recommendation) (moderate quality evidence).

The following clinical and radiological features should determine if a patient has highly active MS:

- Relapse frequency in the previous year (≥2 relapses).

- Relapse severity (pyramidal/cerebellar systems involvement).

- Incomplete recovery from relapses.

- High T2 lesion load on MRI (≥10 lesions), especially with spinal or infratentorial lesions.

- Multiple Gadolinium enhancing lesions (7).

The following clinical and radiological features should determine if a patient has aggressive MS:

- Patients reaching an EDSS score of 6.0 within 5 years of disease onset or by 40 years of age.

- Treatment naïve patients who had 2 or more relapses with incomplete recovery in the past year.

- Two or more disabling relapses in 1 year with ≥1 Gadolinium enhancing lesion or significant high T2 lesion load on MRI (≥10 lesions) (7).

6.2 Switching DMT: Recommendations

Statement 6.2.1: Neurologists should monitor MRI disease activity from the clinical onset of disease to detect the accumulation of new lesions in order to inform treatment decisions in people with MS using DMTs (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

Statement 6.2.2: Neurologists should discuss switching from one DMT to another in MS patients who have been using a DMT long enough for the treatment to take full effect and are adherent to their therapy when they experience 1 or more relapses, 2 or more unequivocally new MRI-detected lesions, or increased disability on examination, over a 1-year period of using a DMT (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

Statement 6.2.3: Neurologists should discuss a medication switch with people with MS for whom these adverse effects negatively influence adherence (6) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

7- How to treat patients with Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis?

Neurologists should offer siponimod for active SPMS patients evidenced by relapses or imaging-features of inflammatory activity (8) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

8- How to treat patients with Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis?

Neurologists should offer ocrelizumab for PPMS patients (9) (strong recommendation) (high quality evidence).

- Implementation consideration

It is advised to provide training courses for the physicians at the centers that provide the DMTs and monitor the response such as training for EDSS scoring, CSF sampling and MRI interpretation.

- Clinical indicators for monitoring

For monitoring of the implementation of the guidelines, the files of the patients presenting with the first clinical demyelinating event should include:

▶️ The date of onset of first MS symptoms

▶️ The results of CSF examination for oligoclonal bands

▶️ The date of staring DMT and the type of provided DMT

- Updating of the guidelines

To keep these recommendations up to date and ensure its validity it will be periodically updated. This will be done whenever strong new evidence is available and necessitates updating.

- Research Needs

1. Assess the usefulness of algorithms for early detecting MS in clinical practice.

2. Develop prognostic indicators to identify the best candidates for follow up.

- Annexes

The different DMTs that are approved for RRMS patients

Interferon Beta:

The use of interferon beta in RRMS is supported by class I evidence derived from multicenter randomized controlled trials. They reduce risk of relapses and disability progression by approximately 30% (10, 11, 12) .

Fingolimod:

Fingolimod was the first oral DMT approved for RRMS based on two phase III clinical trials. It reduced annualized relapse rate by 55% and 52% compared to placebo and Interferon beta 1a IM respectively, and the risk of disability progression by 30% compared to placebo only (13, 14) .

Teriflunomide:

Teriflunomide was approved as an oral DMT based on two phase III clinical trials in patients with RRMS. In the TOWER trial, teriflunomide reduced annualized relapse rate by 36.3% and the risk of disability progression by 31.5% when compared to placebo (15) ,

Dimethyl fumarate:

Dimethy fumarate has been approved as an oral medication for RRMS after the 2 phase III trials DEFINE and CONFIRM, DMF 240 mg twice daily showed a significant reduction in annualized relapse rate (49%), and disability progression (32%) compared to placebo (16) .

Natalizumab:

Natalizumab was the first approved monoclonal antibody for RRMS. In the phase III AFFIRM trial, natalizumab reduced the rate of clinical relapses by 68% and the risk of sustained disability progression by 42% compared to placebo (17).

Ocrelizumab:

Ocrelizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that targets CD20 surface protein on B cells. In 2 similarly designed phase III trials (Opera I and II) involving patients with RRMS, ocrelizumab reduced annualized relapse rate by 46–47% and risk of 24 weeks confirmed disability progression by 37–43% compared to subcutaneous IFNB-1a (18) .

Cladribine:

In a phase III trial, Cladribine administered as oral tablets in four cycles over 2 years, reduced annualized relapse rate by 58% and risk of 6 months confirmed disability progression by 47% compared to placebo. In the extension trial, patients shifted to placebo for the next 2 years showed persistent efficacy of the treatment with 77.8% and 75.6% of patients remaining relapse free during the first 2 years and years 3 and 4 of the extension respectively (19) .

Ponesimod:

Ponesimod was approved as an oral DMT for RRMS patients since it was superior to teriflunomide on annualized relapse rate reduction with a relative rate reduction of 30.5% (20) .

Rituximab:

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that depletes CD20 B cells. Several open label or observational studies from Sweden and other parts of the world supported the efficacy and safety of rituximab in comparison to other disease modifying therapies in patients with MS (21, 22, 23) ,

- References

1- Avasarala J. Redefining Acute Relapses in Multiple Sclerosis: Implications for Phase 3 Clinical Trials and Treatment Algorithms. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017; 14(3-4): 38–40.

2- Repovic P. Management of Multiple Sclerosis Relapses. Continuum: Multiple Sclerosis and other CNS Inflammatory Diseases 2019; volume 25, No.3, p. 655-669.

3- Thompson AJ et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurology 2018; volume 17, issue 2, P162-173.

4- Ziemssen et al. Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2023 Jan; 10(1): e200064.

5- Montalban X et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology 2018, 25: 215-237.

6- Rae-Grant A et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2018; 90:777-788. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347.

7- Yamout et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: 2019 revisions of the MENACTRIMS guidelines. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2020; 37: 101459.

8- Kappos L et al. Siponimod versus placebo in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2018; volume 391, P1263-1273.

9- Montalban X et al. Ocrelizumab versus Placebo in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:209-220.

10- Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The IFNB multiple sclerosis study group. Neurology 43 (4), 655–661.

11- Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/ remitting multiple sclerosis, 1998. PRISMS (Prevention of relapses and disability by interferon beta-1a subcutaneously in multiple sclerosis) study group. Lancet 352 (9139), 1498–1504.

12- Johnson et al., 1995. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The copolymer 1 multiple sclerosis study group. Neurology 45 (7), 1268–1276.

13- Kappos L et al., 2010. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (5), 387–401.

14- Cohen JA et al., 2010. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (5), 402–415.

15- Confavreux C et al., 2014. Oral teriflunomide for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (TOWER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 13 (3), 247–256.

16- Viglietta V et al., 2015. Efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: integrated analysis of the phase 3 trials. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2 (2), 103–118.

17- Polman CH et al., 2006. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (9), 899–910.

18- Hauser SL et al., 2017. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 (3), 221–234.

19- Giovannoni G., et al., 2010. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (5), 416–426.

20- Kappos L et al. Ponesimod Compared With Teriflunomide in Patients With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis in the Active-Comparator Phase 3 OPTIMUM Study: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021 May 1; 78(5):558-567.

21- Rahmanzadeh R. et al., 2018. B cells in multiple sclerosis therapy-A comprehensive review. Acta Neurol. Scand. 137 (6), 544–556.

22- Spelman T et al., 2018. Comparative effectiveness of rituximab relative to IFN-beta or glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting MS from the SWEDISH MS registry. Mult. Scler. 24 (8), 1087–1095.

23- Salzer J et al., 2016. Rituximab in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational study on safety and efficacy. Neurology 87 (20), 2074–2081.