Neuro-Urology

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Urology Surgery Guidelines |

| Book: | Neuro-Urology |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 9:34 PM |

Description

"last update: 15 July 2024"

- Acknowledgement

Guidelines Development Group (GDG) of Neuro-Urology committee.

1. Prof. Mohamed Sherif Mourad, Ain Shams University (Chairl)

2. Prof. AbdelNasser El Gamasy, Tanta University

3. Prof. Ahmed Abulfotooh, Alexandria University

4. Prof. Ahmed Aly Morsy, Cairo University

5. Prof. Ahmed El Baz, Tudor Bilhartz Institute

6. Dr. Ahmed S. Ghonaimy, Menofia University

7. Prof. Hamada Nassar, Damanhour Institute

8. Prof. Hassan Abo Elenein, Mansoura University

9. Prof. Hassan Shaker, Ain Shams University

10. Prof. Hisham Hammouda, Assiut University

11. Assistant Prof. Kareem M. Taha, Zagazig University

12. Prof. Mohamed Ahmed Shalaby, Assiut University

13. Prof. Mohamed Rafik El Halaby, Ain Shams University

14. Prof. Mohamed Wageih, Kobry El kobba Military Hospital

15. Assistant Prof. Wally Mahfouz, Alexandria University

Funding.

No Fundig sources- List of Abbreviations.

|

⏹️ |

ANLUTD Adult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction AUDS Ambulatory Urodynamics AUA American Urological Association AUS Artificial urinary sphincter AD Autonomic Dysreflexia BPO Benign Prostatic Obstruction BP Blood Pressure BM Bowel Management BCR Bulbocavernosus Reflex CVS Cerebrovascular Stroke CIC Clean Intermittent Catheterization DSD Detrusor Sphincter Dyssynergia DUA Detrusor Underactivity DM Diabetes Mellitus DRE Digital Rectal Examination DMSA Dimercaptosuccinic acid ED Erectile Dysfunction EAU European Association of Urology EMG Electromyography FDA Food and Drug Administration FVC-BD Frequency-Volume Chart Bladder Diary GFR Glomerular Filtration Rate IPD Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease ICI International Consultation on Incontinence ICS International Continence Society IPSS International Prostate Symptom Score I-QoL Incontinence Quality of Life IC Intermittent Catheterization IIEF-15 The 15-question International Index of Erectile Function LUT Lower Urinary Tract LUTS Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms LMNL Lower Motor Neuron Lesions MAG3 Mercaptoacetyltriglicine MESA. Microsurgical Epididymal Sperm Aspiration MS Multiple Sclerosis MSA Multiple System Atrophy MMC Myelomeningocele NB Neurogenic Bladder NBSS Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score NLUTD Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Disease NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NDO. Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity OAB Overactive Bladder PS Parkinsonian Syndrome PDE5Is. Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors PMC Pontine Micturition Center PD. Parkinson’s disease PVR. Postvoid Residual RCTs. Randomized Controlled Trials SB Spina Bifida SCI. Spinal Cord Injury TESE Testicular Sperm Extraction TENS Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation TURP Transurethral Resection of The Prostate TOT Trans obturator Tape TVT Transvaginal Tension Free Vaginal Tape UUT Upper Urinary Tract UPP Urethral Pressure Profile UI Urinary Incontinence UTI Urinary Tract Infection UMNL Upper Motor Neuron Lesions UDS Urodynamics VUR Vesico-Ureteral Reflux VUDS Video-Urodynamics VCUG Voiding Cystourethrogram

|

- Glossary

1. Neurogenic bladder: Lower urinary tract dysfunction that has occurred likely as a result of a neurological injury or disease, which may be in the central, autonomic or peripheral nervous systems.

2. Adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (ANLUTD): Abnormal or difficult function of the bladder, urethra (and/ or prostate in men) in mature individuals in the context of clinically confirmed relevant neurologic disorder.

3. Autonomic dysreflexia (AD): A sudden and exaggerated autonomic response to various noxious stimuli in patients with SCI or spinal dysfunction at or above level of T6.

Assisted bladder emptying: These are techniques used by tetraplegic patients who cannot perform clean intermittent catheterization. These include Credé manoeuvre, Valsalva manoeuvre and triggered reflex voiding.- Executive Summary

|

⏹️ |

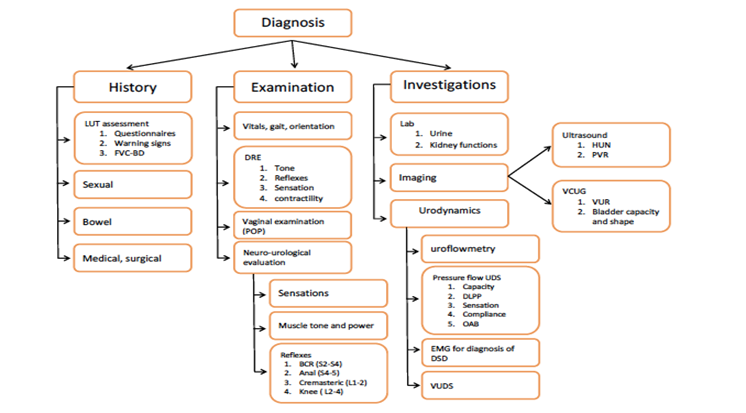

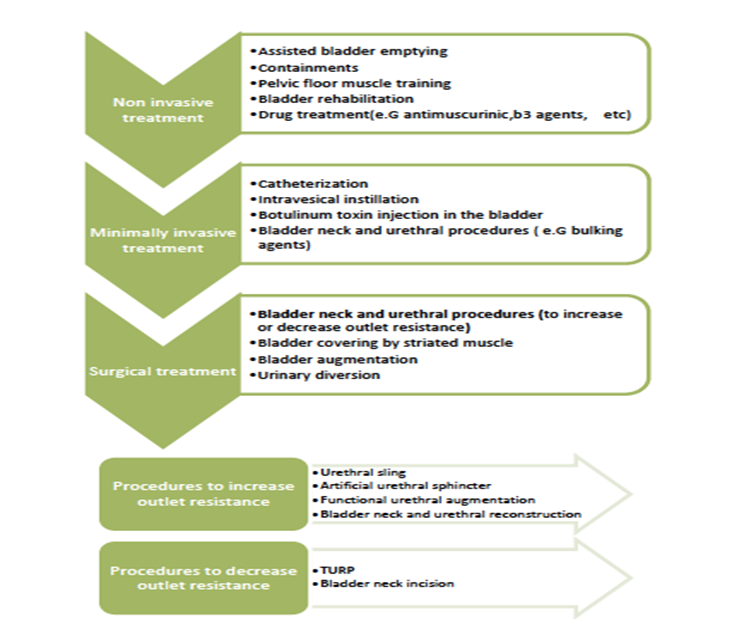

Scope of the guidelines. These guidelines deals with the diagnosis and management of patients with NLUTD. Extensive history taking, thorough examination together with laboratory, radiological and urodynamic investigations should be done in every NLUTD patient. Accordingly, tailoring and individualizing the plan of management follows. Recommendations. 1. Take extensive general history focusing on past and present symptoms, with special emphasis on four main domains: urinary, sexual, bowel and neurological functions (STRONG) 2. Assess Quality of life with validated QoL questionnaires for neuro-urological patients (STRONG) 3. Drug, family, past and present history of neurologic and non-neurologic diseases along with history of external and iatrogenic trauma should be properly taken from patients with NLUTD (STRONG) 4. Special attention should be paid to warning signs such as fever, hematuria, dysuria, leaking around catheter and autonomic dysreflexia, which could alter/change diagnosis and thus affect the current management (STRONG) 5. Perineal and genital examination should be performed, including motor and sensory assessment beside specific lumbosacral reflexes (STRONG) 6. The anal sphincter activity and pelvic floor muscles should be tested (STRONG) 7. Urine analysis should be performed in the initial evaluation of NLUTD as it has a role in exclusion of UTI in NB patients. It can be also used for following up after antibiotic treatment(STRONG) 8. Assessment of renal functions is essential in diagnosis and follow-up of NLUTD patients. GFR can be best measured by Cystatin-C based GFR for assessment of renal function (STRONG) 9. Renal ultrasound should be done in primary assessment of NLUTD to evaluate UUT anatomy (STRONG) 10. Perform bladder ultrasound with PVR measurement in the primary evaluation of NLUTD patients (STRONG) 11. VCUG is recommended in neuro-urological patients to assess the bladder capacity, detect VUR if present and estimate PVR (STRONG) 12. Perform uroflowmetry in NLUTD patients who can void (STRONG) 13. Perform a urodynamic investigation to detect and specify LUTD, use same session repeat measurement. Use body-warmed saline, 6 Fr. double lumen urodynamic urethral catheter and filling rate starting at 10 ml/min. If there is no rise in the Pdet, this can be increased to 20 ml/min (STRONG) 14. Use VUDS in neuro-urological patients. if not, pressure-flow study may be used instead with VCUG(STRONG) 15. EMG, with surface perineal electrodes, could be used if DSD is suspected in NB patients (CONDITIONAL) 16. Do not perform assisted bladder emptying techniques (Crede, Valsalva or triggered reflex voiding) as they are hazardous to the upper tract EXCEPT in patients with absent or surgically removed outlet resistance (STRONG) 17. Do not offer penile clamps as they are absolutely contraindicated in cases of NDO or low bladder compliance because of the risk of developing high intravesical pressure and pressure sores/necrosis in cases of altered/absent sensations (STRONG) 18. Prescribe anticholinergics as the first-line medical therapy for NDO (STRONG) 19. Offer combination therapy of antimuscarinics and Beta 3 agonists to maximise outcomes for NDO (STRONG) 20. Prescribe α-blockers to decrease bladder outlet resistance in NLUTD, putting into consideration their off -label in patients with DSD (CONDITIONAL) 21. Use CIC as a standard treatment for patients who are unable to empty their bladder. The average catheterisation schedule is four to six times per day. Use catheter size of 12-16 Fr. Bladder volume should not exceed 400-500 mL at catheterization time (STRONG) 22. Do not use Foley catheters because of the high incidence of latex allergy in the neuro-urological patient population. Use silicone catheters instead (STRONG) 23. Avoid use of indwelling transurethral and suprapubic catheterisation whenever possible (STRONG) 24. Offer intradetrusor botulinum toxin injection to reduce NDO when antimuscarinic therapy fails. The recommended dose of intradetrusal botulinum toxin injection in neurogenic bladder is 200 IU, in 30 sites in the bladder, with exclusion of the trigone, for theoretical prevention of VUR (STRONG) 25. Offer bladder neck incision in a fibrotic sclerotic bladder neck (STRONG) 26. Offer botulinum toxin A 100 IU intrasphincteric in cases of DSD (STRONG) 27. Offer pubovaginal sling in neuro-urological females with decreased outlet resistance who can do self-catheterization (STRONG) 28. Offer TOT and TVT to neuro-urological females with decreased outlet resistance(STRONG) 29. Insert an AUS in male patients with neurogenic stress urinary incontinence (STRONG) 30. Offer bladder augmentation as an alternative to treat refractory NDO and/or impaired bladder compliance (STRONG) 31. Recommend urinary diversion when no other therapy is successful for NDO and/or impaired bladder compliance (STRONG) 32. Do not perform screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria nor treat it in NLUTD patients (STRONG) 33. Avoid the prescription of long-term antibiotics for recurrent UTIs (STRONG) 34. Prescribe oral PDE5I as first-line medical treatment in neurogenic ED(STRONG) 35. Offer intracavernous injections of vasoactive drugs as second-line medical treatment in neurogenic ED (STRONG) 36. Offer penile prostheses for selected NLUTD patients when all other treatments have failed (STRONG) 37. Perform vibrostimulation and transrectal electroejaculation for sperm retrieval in men with SCI (STRONG) 38. Do not offer medical therapy for the treatment of neurogenic sexual dysfunction in women (STRONG) 39. Assess the upper urinary tract every six months in high-risk patients (those with high Pdet/hypocompliant bladders/DSD) by ultrasonography (STRONG) 40. Perform a physical examination and urine analysis and culture every year in high-risk patients (those with high Pdet/hypocompliant bladders/DSD) (STRONG) 41. Perform UDS as a mandatory baseline diagnostic intervention. It is recommended yearly in high-risk group, otherwise could be done every two years (STRONG)

|

- Introduction, purpose, scope and audience

|

⏹️ |

Introduction. Neurological diseases are vast, and they may have adverse consequences on the urinary system. The extent and site of the neurological insult will determine the type of neurogenic lower urinary tract disease (NLUTD). The term “neurogenic bladder” describes lower urinary tract dysfunction that has occurred likely as a result of a neurological injury or disease (1) which may be in the central, autonomic or peripheral nervous systems. The International Continence Society (ICS) defines “Adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction" (ANLUTD) as abnormal or difficult function of the bladder, urethra (and/ or prostate in men) in mature individuals in the context of clinically confirmed relevant neurologic disorder (2). Neuro-urological disorders are classified according to Panicker et al. into (3): i. Suprapontine and pontine lesions (Upper motor neuron lesions = UMNL) ii. Spinal (Infrapontine and suprasacral) lesions (UMNL) iii. Sacral and infrasacral lesions (Lower motor neuron lesions = LMNL) The current classification systems serve as a framework since it is not possible to map all lesions and its consequences in every patient in a single classification (4). Most of these systems are of no use today such as: Lapides (1970), Bors and Comarr (1971)& Wein functional classification (1981). More recently, other classification systems were described according to pattern of clinical urological and urodynamic manifestations and aimed to predict site of neurologic affection. The most commonly used are The Madersbacher system and the system described by Panicker et al. The worst complication of NLUTD is upper urinary tract (UUT) deterioration, which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this subset of patients. UUT deterioration is more with spinal cord injury (SCI) and spine bifida (SB) patients. It is very crucial to stratify NLUTD patients into high and low risk groups and their lesions according into upper and lower motor neuron lesions, to individualize the plan of management and follow up thus preventing further deterioration and complications. Therefore, early diagnosis (Figure 1), treatment (Figure 2) and follow-up of these patients are crucial. The main goals of management for NLUTD are satisfaction and avoidance of adverse outcomes which includes (5,6): • Protecting upper urinary tract from sustained high filling and voiding pressures (Pdet >40 cmH2O). • Achieving regular bladder emptying, avoiding stasis and bladder over distension, and minimizing PVR to less than 100mls. • Preventing and treating complications such as UTIs, stones, strictures and AD • Achievement (or maintenance) of urinary continence (Social goal). • Restoration of LUT function (Adequate storage and emptying at low intravesical pressure). • Improvement of the patient’s QoL. The time interval between initial investigations and control diagnostics should not exceed one to two years. In high-risk neuro-urological patients, this interval should be much shorter. Purpose. The Urologic Egyptian Guidelines on Neuro-Urology aim to help and guide clinical practitioners to have knowledge of the incidence, standard definitions, diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up of NLUTD. This document integrates recent international guidelines with local experts’ opinions based on Egyptian healthcare and socioeconomic circumstances. It also reflects the opinions of experts in Neuro-Urology and represents state-of-the art references for all clinicians, as of the publication date Target Audience. ▪️ Urologists▪️ Gynecologists ▪️ Neurologists and Neurosurgeons ▪️ General Practitioners |

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

Inclusion vidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

▪️Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

▪️ Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later)

▪️ Selecting peer reviewed publications only

▪️ Selecting guidelines written in English language

▪️ Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input

▪️ Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

• Developing organisation/authors

• Date of publication, posting, and release

• Country/language of publication

• Date of posting and/or release

• Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. the panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 50% on the rigour dimension was retained) (2,7,8)

➡️Evidence assessment:

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations (9,10). GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

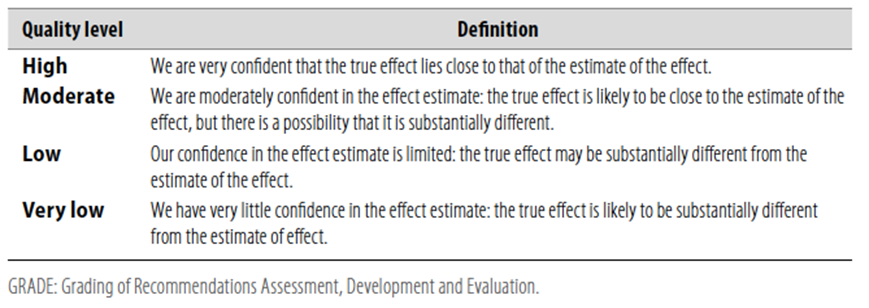

Table 1 Quality of evidence in GRADE

Table 2 Significance of the four levels of evidence

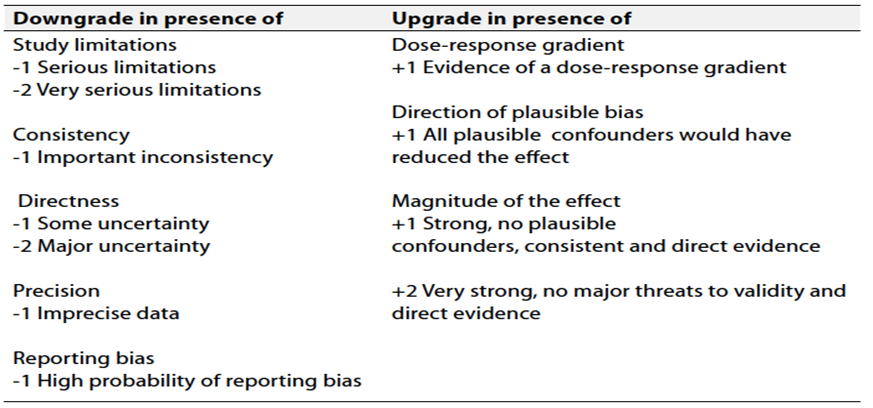

Table 3 Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of evidence

➡️The strength of the recommendation.

The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

➡️Strong recommendations.

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

➡️Conditional recommendations.

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

➡️When not to make recommendations.

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

➡️Databases searched included Medline, Cochrane Libraries, European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines, ICS recommendations, 6th International consultation on incontinence (ICI) recommendations, American Urological Association (AUA) and NICE guidelines, in the period from January 2018 and September 2022.

Adaptation of the Egyptian cultural aspects, the level of urologists’ capabilities and the availability of well equipped hospitals were considered in the methodology of diagnosis and different treatment modalities.

- Recommendations

Table 4: Recommendations for investigations of NB

|

Recommendations |

GRADE Level of certainty |

Strength Rating |

|

1. Take extensive general history focusing on past and present symptoms, with special emphasis on four main domains: urinary, sexual, bowel and neurological functions |

High (11-17) |

Strong |

|

2. Assess Quality of life with validated QoL questionnaires for neuro-urological patients |

Moderate (18-26) |

Strong |

|

3. Drug, family, past and present history of neurologic and non-neurologic diseases along with history of external and iatrogenic trauma should be properly taken from patients with NLUTD |

High(11,14,16) |

Strong |

|

4. Special attention should be paid to warning signs such as fever, hematuria, dysuria, leaking around catheter and autonomic dysreflexia, which could alter/change diagnosis and thus affect the current management |

High (27,28) |

Strong |

|

5. Perineal and genital examination should be performed, including motor and sensory assessment beside specific lumbosacral reflexes |

High (29,30) |

Strong |

|

6. The anal sphincter activity and pelvic floor muscles should be tested |

Moderate(31) |

Strong |

|

7. Urine analysis should be performed in the initial evaluation of NLUTD as it has a role in exclusion of UTI in NB patients. It can be also used for following up after antibiotic treatment |

High (32,33) |

Strong |

|

8. Assessment of renal functions is essential in diagnosis and follow-up of NLUTD patients. GFR can be best measured by Cystatin-C based GFR for assessment of renal function.

|

Moderate (32,33-35) |

Strong |

|

9. Renal ultrasound should be done in primary assessment of NLUTD to evaluate UUT anatomy |

Moderate (32,33) |

Strong |

|

10. Perform bladder ultrasound with PVR measurement in the primary evaluation of NLUTD patients |

High (32,33) |

Strong |

|

11. VCUG is recommended in neuro-urological patients to assess the bladder capacity, detect VUR if present and estimate PVR |

Moderate (32,33) |

Strong |

|

12. Perform uroflowmetry in NLUTD patients who can void |

High (36,37) |

Strong |

|

13. Perform a urodynamic investigation to detect and specify LUTD, use same session repeat measurement. Use body-warmed saline, 6 Fr. double lumen urodynamic urethral catheter and filling rate starting at 10 ml/min. If there is no rise in the Pdet, this can be increased to 20 ml/min. |

Moderate (12,36-39) |

Strong |

|

14. Use VUDS in neuro-urological patients. if not, pressure-flow study may be used instead with VCUG |

Moderate (40,41) |

Strong |

|

15. EMG, with surface perineal electrodes, could be used if DSD is suspected in NB patients |

Low (42) |

Conditional |

Table 5:Recommendations for treatment of NB

|

Recommendations |

GRADE Level of certainty |

Strength Rating |

|

1. Do not perform assisted bladder emptying techniques (Crede, Valsalva or triggered reflex voiding) as they are hazardous to the upper tract EXCEPT in patients with absent or surgically removed outlet resistance |

Moderate (43-46) |

Strong |

|

2. Do not offer penile clamps as they are absolutely contraindicated in cases of NDO or low bladder compliance because of the risk of developing high intravesical pressure and pressure sores/necrosis in cases of altered/absent sensations |

High (43) |

Strong |

|

3. Prescribe anticholinergics as the first-line medical therapy for NDO |

High (46-52) |

Strong |

|

4. Offer combination therapy of antimuscarinics and Beta 3 agonists to maximise outcomes for NDO |

High (53-62) |

Strong |

|

5. Prescribe α-blockers to decrease bladder outlet resistance in NLUTD, putting into consideration their off -label in patients with DSD |

Low (63-65) |

Conditional |

|

6. Use CIC as a standard treatment for patients who are unable to empty their bladder. The average catheterisation schedule is four to six times per day. Use catheter size most of 12-16 Fr. Bladder volume should not exceed 400-500 mL at catheterization time |

Moderate (43, 66-69) |

Strong |

|

7. Do not use Foley catheters because of the high incidence of latex allergy in the neuro-urological patient population. Use silicone catheters instead |

Moderate (70) |

Strong |

|

8. Avoid use of indwelling transurethral and suprapubic catheterisation whenever possible |

Moderate (71-74) |

Strong |

|

9. Offer intradetrusor botulinum toxin injection to reduce NDO when antimuscarinic therapy fails. The recommended dose of intradetrusal botulinum toxin injection in neurogenic bladder is 200 IU, in 30 sites in the bladder, with exclusion of the trigone, for theoretical prevention of VUR |

High(75-82) |

Strong |

|

10. Offer bladder neck incision in a fibrotic sclerotic bladder neck |

High (83-85) |

Strong |

|

11. Offer botulinum toxin A 100 IU intrasphincteric in cases of DSD |

Moderate(86-89) |

Strong |

|

12. Offer pubovaginal sling in neuro-urological females with decreased outlet resistance who can do self-catheterization |

Moderate (90-93) |

Strong |

|

13. Offer TOT and TVT to neuro-urological females with decreased outlet resistance |

High (94-96) |

Strong |

|

14. Insert an AUS in male patients with neurogenic stress urinary incontinence (SUI) |

Moderate (97-99) |

Strong |

|

15. Offer bladder augmentation as an alternative to treat refractory NDO and/or impaired bladder compliance |

Moderate (100-104) |

Strong |

|

16. Recommend urinary diversion when no other therapy is successful for NDO and/or impaired bladder compliance |

Moderate(105-107) |

Strong |

|

17. Do not perform screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria nor treat it in NLUTD patients |

High (108-110) |

Strong |

|

18. Avoid the prescription of long-term antibiotics for recurrent UTIs |

High (111-113) |

Strong |

|

19. Prescribe oral PDE5I as first-line medical treatment in neurogenic ED |

High (114-117) |

Strong |

|

20. Offer intracavernous injections of vasoactive drugs as second-line medical treatment in neurogenic ED |

Moderate (118-120) |

Strong |

|

21. Offer penile prostheses for selected NLUTD patients when all other treatments have failed |

Hig (115, 121,122) |

Strong |

|

22. Perform vibrostimulation and transrectal electroejaculation for sperm retrieval in men with SCI |

Moderate(123-126) |

Strong |

|

23. Do not offer medical therapy for the treatment of neurogenic sexual dysfunction in women |

Moderate(115, 127,128) |

Strong |

|

24. Assess the upper urinary tract every six months in high-risk patients (those with high Pdet/hypocompliance/DSD)by ultrasonography |

Moderate(32,129-131) |

Strong |

|

25. Perform a physical examination and urine analysis and culture every year in high-risk patients (those with high Pdet/hypocompliance/DSD) |

Moderate(32,129-131) |

Strong |

|

26. Perform UDS as a mandatory baseline diagnostic intervention. It is recommended yearly in high-risk group, otherwise could be done every two years |

Moderate(32,129-131) |

Strong |

- Clinical indicators for monitoring

1. Renal function tests (urea, creatinine)

2. Urine analysis and urine culture and sensitivity

3. Cystatin-based GFR

4. Uroflowmetry

5. Pressure-flow study

6. Ultrasound abdomen and pelvis

➡️Update of guidelines

These guidelines will be updated whenever there is new evidence.- References

1. Cameron AP. Pharmacologic therapy for the neurogenic bladder. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2010;37(4):495.

2. Gajewski JB, Schurch B, Hamid R, Averbeck M, Sakakibara R, Agrò EF, et al. An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (ANLUTD). Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018;37(3):1152-1161.

3. Panicker JN, Fowler CJ, Kessler TM. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in the neurological patient: clinical assessment and management. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14(7):720-732.

4. Madersbacher H, Gajewski JB. Classification and Terminology of Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction. In: Liao L, Madersbacher H, editors. Neurourology: Theory and Practice. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2019: 133-140.

5. Lose G, Griffiths D, Hosker G, Kulseng‐Hanssen S, Perucchini D, Schäfer W, et al. Standardisation of urethral pressure measurement: report from the Standardisation Sub‐Committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics: Official Journal of the International Continence Society. 2002;21(3):258-360.

6. De Wachter S. Ambulatory Urodynamics. In: Liao L, Madersbacher H, editors. Neurourology: Theory and Practice. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2019. p. 165-.

7. Andrea M Sartori , Thomas M Kessler , David M Castro-Díaz , Peter de Keijzer , Giulio Del Popolo, Hazel Ecclestone et al. Summary of the 2024 Update of the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Neurourology. Eur Urol 2024 Jun;85(6):543-555.

8. David A Ginsberg, Timothy B Boone, Anne P Cameron, Angelo Gousse, Melissa R Kaufman, Erick Keays , Michael J Kennelly. The AUA/SUFU Guideline on Adult Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Diagnosis and Evaluation. J Urol 2021 Nov;206(5):1097-1105.

9. Guyatt, G.H., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 2008. 336: 924.

10. Guyatt, G.H., et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ, 2008. 336: 995.

11. Watanabe, T., et al. High incidence of occult neurogenic bladder dysfunction in neurologically intact patients with thoracolumbar spinal injuries. J Urol, 1998. 159: 965.

12. Cetinel, B., et al. Risk factors predicting upper urinary tract deterioration in patients with spinal cord injury: A retrospective study. Neurourol Urodyn, 2017. 36: 653.

13. Elmelund, M., et al. Renal deterioration after spinal cord injury is associated with length of detrusor contractions during cystometry-A study with a median of 41 years follow-up. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016.

14. Ineichen, B.V., et al. High EDSS can predict risk for upper urinary tract damage in patients with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 2017. 1352458517703801: 01.

15. Bors, E., et al. History and physical examination in neurological urology. J Urol, 1960. 83: 759.

16. Cameron, A.P., et al. The Severity of Bowel Dysfunction in Patients with Neurogenic Bladder. J Urol, 2015.

17. Vodusek, D.B. Lower urinary tract and sexual dysfunction in neurological patients. Eur Neurol, 2014. 72: 109.

18. Henze, T. Managing specific symptoms in people with multiple sclerosis. Int MS J, 2005. 12: 60.

19. Liu, C.W., et al. The relationship between bladder management and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury in the UK. Spinal Cord, 2010. 48: 319.

20. Bonniaud, V., et al. Development and validation of the short form of a urinary quality of life questionnaire: SF-Qualiveen. J Urol, 2008. 180: 2592.

21. Patel, D.P., et al. Patient reported outcomes measures in neurogenic bladder and bowel: A systematic review of the current literature. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016. 35: 8.

22. Best, K.L., et al. Identifying and classifying quality of life tools for neurogenic bladder function after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med, 2017. 40: 505.

23. Gulick, E.E. Bowel management related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: psychometric evaluation of the QoL-BM measure. Int J Nurs Stud, 2011. 48: 1066.

24. Schurch, B., et al. Reliability and validity of the Incontinence Quality of Life questionnaire in patients with neurogenic urinary incontinence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2007. 88: 646.

25. Foley, F.W., et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire -- re-validation and development of a 15-item version with a large US sample. Mult Scler, 2013. 19: 1197.

26. Sanders, A.S., et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Intimacy and Sexuality Questionnaire-19 (MSISQ-19). Sex Disabil, 2000. 18: 3.

27. Linsenmeyer, T.A., et al. Accuracy of individuals with spinal cord injury at predicting urinary tract infections based on their symptoms. J Spinal Cord Med, 2003. 26: 352.

28. Massa, L.M., et al. Validity, accuracy, and predictive value of urinary tract infection signs and symptoms in individuals with spinal cord injury on intermittent catheterization. J Spinal Cord Med, 2009. 32: 568.

29. Husmann, D.A. Mortality following augmentation cystoplasty: A transitional urologist’s viewpoint. J Pediatr Urol, 2017.

30. Yang, C.C., et al. Bladder management in women with neurologic disabilities. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2001. 12: 91.

31. Podnar, S., et al. Protocol for clinical neurophysiologic examination of the pelvic floor. Neurourol Urodyn, 2001. 20: 669.

32. Panicker, J.N., et al. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in the neurological patient: clinical assessment and management. Lancet Neurol, 2015. 14: 720.

33. Podnar, S., et al. Protocol for clinical neurophysiologic examination of the pelvic floor. Neurourol Urodyn, 2001. 20: 669.

34. Dangle, P.P., et al. Cystatin C-calculated Glomerular Filtration Rate-A Marker of Early Renal Dysfunction in Patients With Neuropathic Bladder. Urology, 2017. 100: 213.

35. Mingat, N., et al. Prospective study of methods of renal function evaluation in patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Urology, 2013. 82: 1032.

36. Schafer, W., et al. Good urodynamic practices: uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol Urodyn, 2002. 21: 261.

37. Bellucci, C.H., et al. Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction--do we need same session repeat urodynamic investigations? J Urol, 2012. 187: 1318.

38. McGuire, E.J., et al. Leak-point pressures. Urol Clin North Am, 1996. 23: 253.

39. Musco, S., et al. Value of urodynamic findings in predicting upper urinary tract damage in neurourological patients: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn, 2018.

40. Nosseir, M., et al. Clinical usefulness of urodynamic assessment for maintenance of bladder function in patients with spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn, 2007. 26: 228.

41. Marks, B.K., et al. Videourodynamics: indications and technique. Urol Clin North Am, 2014. 41: 383

42. Bacsu, C.D., et al. Diagnosing detrusor sphincter dyssynergia in the neurological patient. BJU Int, 2012. 109 Suppl 3: 31.

43. Apostolidis, A., et al., Neurologic Urinary and Faecal Incontinence, In: Incontinence 6th Edition, P. Abrams, L. Cardozo, S. Khoury & A. Wein, Editors. 2017.

44. Barbalias, G.A., et al. Critical evaluation of the Crede maneuver: a urodynamic study of 207 patients. J Urol, 1983. 130: 720.

45. Reinberg, Y., et al. Renal rupture after the Crede maneuver. J Pediatr, 1994. 124: 279.

46. Wyndaele, J.J., et al. Neurologic urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn, 2010. 29: 159.

47. Thomas, L.H., et al. Treatment of urinary incontinence after stroke in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008: CD004462.

48. Phe, V., et al. Management of neurogenic bladder in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nature Reviews Urology, 2016. 13: 275.

49. Madersbacher, H., et al. Neurogenic detrusor overactivity in adults: a review on efficacy, tolerability and safety of oral antimuscarinics. Spinal Cord, 2013. 51: 432.

50. Madhuvrata, P., et al. Anticholinergic drugs for adult neurogenic detrusor overactivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 816.

51. Mehnert, U., et al. The management of urinary incontinence in the male neurological patient. Curr Opin Urol, 2014. 24: 586.

52. Stothers, L., et al. An integrative review of standardized clinical evaluation tool utilization in anticholinergic drug trials for neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Spinal Cord, 2016. 31: 31.

53. Bennett, N., et al. Can higher doses of oxybutynin improve efficacy in neurogenic bladder? J Urol, 2004. 171: 749.

54. Horstmann, M., et al. Neurogenic bladder treatment by doubling the recommended antimuscarinic dosage. Neurourol Urodyn, 2006. 25: 441.

55. Amend, B., et al. Effective treatment of neurogenic detrusor dysfunction by combined high-dosed antimuscarinics without increased side-effects. Eur Urol, 2008. 53: 1021.

56. Nardulli, R., et al. Combined antimuscarinics for treatment of neurogenic overactive bladder. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol, 2012. 25: 35s.

57. Tijnagel, M.J., et al. Real life persistence rate with antimuscarinic treatment in patients with idiopathic or neurogenic overactive bladder: a prospective cohort study with solifenacin. BMC Urology, 2017. 17: 13.

58. Krhut, J., et al. Efficacy and safety of mirabegron for the treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity-Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurourol Urodyn, 2018. 37: 2226.

59. Welk, B., et al. A pilot randomized-controlled trial of the urodynamic efficacy of mirabegron for patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn, 2018. 37: 2810.

60. Chen, S.F., et al. Therapeutic efficacy of low-dose (25mg) mirabegron therapy for patients with mild to moderate overactive bladder symptoms due to central nervous system diseases. LUTS: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, 2018.

61. Peyronnet, B., et al. Mirabegron in patients with Parkinson disease and overactive bladder symptoms: A retrospective cohort. Parkinsonism Rel Disord, 2018. 57: 22.

62. Zachariou, A., et al. Effective treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity in multiple sclerosis patients using desmopressin and mirabegron. Can J Urol, 2017. 24: 9107.

63. Abrams, P., et al. Tamsulosin: efficacy and safety in patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction due to suprasacral spinal cord injury. J Urol, 2003. 170: 1242.

64. Gomes, C.M., et al. Neurological status predicts response to alpha-blockers in men with voiding dysfunction and Parkinson’s disease. Clinics, 2014. 69: 817.

65. Moon, K.H., et al. A 12-week, open label, multi-center study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of silodosin on voiding dysfunction in patients with neurogenic bladder. LUTS: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms, 2015. 7: 27.

66. Guttmann, L., et al. The value of intermittent catheterisation in the early management of traumatic paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia, 1966. 4: 63.

67. Lapides, J., et al. Clean, intermittent self-catheterization in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol, 1972. 107: 458.

68. Prieto, J., et al. Intermittent catheterisation for long-term bladder management. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014: CD006008.

69. Prieto-Fingerhut, T., et al. A study comparing sterile and nonsterile urethral catheterization in patients with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Nurs, 1997. 22: 299.

70. Hollingsworth, J.M., et al. Determining the noninfectious complications of indwelling urethral catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med, 2013. 159: 401.

71. Bennett, C.J., et al. Comparison of bladder management complication outcomes in female spinal cord injury patients. J Urol, 1995. 153: 1458.

72. Larsen, L.D., et al. Retrospective analysis of urologic complications in male patients with spinal cord injury managed with and without indwelling urinary catheters. Urology, 1997. 50: 418.

73. Weld, K.J., et al. Effect of bladder management on urological complications in spinal cord injured patients. J Urol, 2000. 163: 768.

74. Lavelle, R.S., et al. Quality of life after suprapubic catheter placement in patients with neurogenic bladder conditions. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016. 35: 831.

75. Del Popolo, G., et al. Neurogenic detrusor overactivity treated with english botulinum toxin a: 8-year experience of one single centre. Eur Urol, 2008. 53: 1013.

76. Yuan, H., et al. Efficacy and Adverse Events Associated With Use of OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity: A Meta-Analysis. Int Neurourol J, 2017. 21: 53.

77. Cheng, T., et al. Efficacy and Safety of OnabotulinumtoxinA in Patients with Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One, 2016. 11: e0159307.

78. Wagle Shukla, A., et al. Botulinum Toxin Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Seminars in Neurology, 2017. 37: 193.

79. Grosse, J., et al. Success of repeat detrusor injections of botulinum a toxin in patients with severe neurogenic detrusor overactivity and incontinence. Eur Urol, 2005. 47: 653.

80. Rovner, E., et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of OnabotulinumtoxinA in Patients with Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity Who Completed 4 Years of Treatment. J Urol, 2016.

81. Ni, J., et al. Is repeat Botulinum Toxin A injection valuable for neurogenic detrusor overactivity-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn, 2018. 37: 542.

82. Michel, F., et al. Botulinum toxin type A injection after failure of augmentation enterocystoplasty performed for neurogenic detrusor overactivity: preliminary results of a salvage strategy. The ENTEROTOX study. Urology, 2019.

83. Stöhrer, M., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bladder dysfunction in spinal cord injury patients. Eur Urol Update Series 1994. 3: 170

84. Derry, F., et al. Audit of bladder neck resection in spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord, 1998. 36: 345.

85. Perkash, I. Use of contact laser crystal tip firing Nd:YAG to relieve urinary outflow obstruction in male neurogenic bladder patients. J Clin Laser Med Surg, 1998. 16: 33.

86. Dykstra, D.D., et al. Treatment of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia with botulinum A toxin: a doubleblind study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1990. 71: 24.

87. Schurch, B., et al. Botulinum-A toxin as a treatment of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia: a prospective study in 24 spinal cord injury patients. J Urol, 1996. 155: 1023.

88. Huang, M., et al. Effects of botulinum toxin A injections in spinal cord injury patients with detrusor overactivity and detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. J Rehabil Med, 2016. 48: 683.

89. Utomo, E., et al. Surgical management of functional bladder outlet obstruction in adults with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014. 5: CD004927.

90. Barthold, J.S., et al. Results of the rectus fascial sling and wrap procedures for the treatment of neurogenic sphincteric incontinence. J Urol, 1999. 161: 272.

91. Gormley, E.A., et al. Pubovaginal slings for the management of urinary incontinence in female adolescents. J Urol, 1994. 152: 822.

92. Kakizaki, H., et al. Fascial sling for the management of urinary incontinence due to sphincter incompetence. J Urol, 1995. 153: 644.

93. Mingin, G.C., et al. The rectus myofascial wrap in the management of urethral sphincter incompetence. BJU Int, 2002. 90: 550.

94. Abdul-Rahman, A., et al. Long-term outcome of tension-free vaginal tape for treating stress incontinence in women with neuropathic bladders. BJU Int, 2010. 106: 827.

95. Losco, G.S., et al. Long-term outcome of transobturator tape (TOT) for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in females with neuropathic bladders. Spinal Cord, 2015. 53: 544.

96. El-Azab, A.S., et al. Midurethral slings versus the standard pubovaginal slings for women with neurogenic stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J, 2015. 26: 427.

97. Light, J.K., et al. Use of the artificial urinary sphincter in spinal cord injury patients. J Urol, 1983. 130: 1127.

98. Farag, F., et al. Surgical treatment of neurogenic stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review of quality assessment and surgical outcomes. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016. 35: 21.

99. Kim, S.P., et al. Long-term durability and functional outcomes among patients with artificial urinary sphincters: a 10-year retrospective review from the University of Michigan. J Urol, 2008. 179: 1912.

100. Vainrib, M., et al. Differences in urodynamic study variables in adult patients with neurogenic bladder and myelomeningocele before and after augmentation enterocystoplasty. Neurourol Urodyn, 2013. 32: 250.

101. Krebs, J., et al. Functional outcome of supratrigonal cystectomy and augmentation ileocystoplasty in adult patients with refractory neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn, 2016.

102. Hoen, L., et al. Long-term effectiveness and complication rates of bladder augmentation in patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn, 2017. 07: 07.

103. Myers, J.B., et al. The effects of augmentation cystoplasty and botulinum toxin injection on patient reported bladder function and quality of life among individuals with spinal cord injury performing clean intermittent catheterization. Neurourol Urodyn, 2019. 38: 285.

104. Mitsui, T., et al. Preoperative renal scar as a risk factor of postoperative metabolic acidosis following ileocystoplasty in patients with neurogenic bladder. Spinal Cord, 2014. 52: 292.

105. Moreno, J.G., et al. Improved quality of life and sexuality with continent urinary diversion in quadriplegic women with umbilical stoma. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1995. 76: 758.

106. Phe, V., et al. Continent catheterizable tubes/stomas in adult neuro-urological patients: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn, 2017.

107. Sakhri, R., et al. [Laparoscopic cystectomy and ileal conduit urinary diversion for neurogenic bladders and related conditions. Morbidity and better quality of life]. Prog Urol, 2015. 25: 342.

108. Bakke, A., et al. Bacteriuria in patients treated with clean intermittent catheterization. Scand J Infect Dis, 1991. 23: 577.

109. Nicolle, L.E., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis, 2005. 40: 643.

110. Goetz, L.L., et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Urinary Tract Infection Basic Data Set. Spinal Cord, 2013. 51: 700.

111. Everaert, K., et al. Urinary tract infections in spinal cord injury: prevention and treatment guidelines. Acta Clin Belg, 2009. 64: 335.

112. Lee, B.S., et al. Methenamine hippurate for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012. 10: CD003265.

113. Hachen, H.J. Oral immunotherapy in paraplegic patients with chronic urinary tract infections: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Urol, 1990. 143: 759.

114. Rees, P.M., et al. Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders. Lancet, 2007. 369:512.

115. Lombardi, G., et al. Management of sexual dysfunction due to central nervous system disorders: a systematic review. BJU Int, 2015. 115 Suppl 6: 47.

116. Chen, L., et al. Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction: A Trade-off Network Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2015. 68: 674.

117. Lombardi, G., et al. Treating erectile dysfunction and central neurological diseases with oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. Review of the literature. J Sex Med, 2012. 9: 970.

118. Bella, A.J., et al. Intracavernous pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction. Endocrine, 2004. 23: 149.

119. Kapoor, V.K., et al. Intracavernous papaverine for impotence in spinal cord injured patients. Paraplegia, 1993. 31: 675.

120. Vidal, J., et al. Intracavernous pharmacotherapy for management of erectile dysfunction in multiple sclerosis patients. Rev Neurol, 1995. 23: 269.

121. Gross, A.J., et al. Penile prostheses in paraplegic men. Br J Urol, 1996. 78: 262.

122. Kimoto, Y., et al. Penile prostheses for the management of the neuropathic bladder and sexual dysfunction in spinal cord injury patients: long term follow up. Paraplegia, 1994. 32: 336.

123. Kolettis, P.N., et al. Fertility outcomes after electroejaculation in men with spinal cord injury. Fertil Steril, 2002. 78: 429.

124. Chehensse, C., et al. The spinal control of ejaculation revisited: a systematic review and metaanalysis of anejaculation in spinal cord injured patients. Hum Reprod Update, 2013. 19: 507.

125. Beretta, G., et al. Reproductive aspects in spinal cord injured males. Paraplegia, 1989. 27: 113.

126. Brackett, N.L., et al. Application of 2 vibrators salvages ejaculatory failures to 1 vibrator during penile vibratory stimulation in men with spinal cord injuries. J Urol, 2007. 177: 660.

127. Westgren, N., et al. Sexuality in women with traumatic spinal cord injury. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1997. 76: 977.

128. Fruhauf, S., et al. Efficacy of psychological interventions for sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav, 2013. 42: 915.

129. Przydacz, M., et al. Recommendations for urological follow-up of patients with neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury. Int Urol Nephrol, 2018. 50: 1005.

130. Abrams, P., et al. A proposed guideline for the urological management of patients with spinal cord injury. BJU Int, 2008. 101: 989.

131. B. Blok (Chair) DC-D, G. Del Popolo JG, R. Hamid, G. Karsenty, T.M. Kessler, (Vice-chair) JP, Guidelines Associates: H. Ecclestone SM, B. Padilla-Fernández AS, L.A. ‘t Hoen. EAU guidelines on Neuro-Urology. EAU extended guidelines. 2020; 2020:53

- Annexes

Figure 1. Diagnosis of NLUTD

Figure 2. Treatment algorithm of NLUTD