PHONIATRICS Brain damage motor handicap BDMH CORRECTED

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Otorhinolaryngology, Audiovestibular & Phoniatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | PHONIATRICS Brain damage motor handicap BDMH CORRECTED |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 9:50 PM |

Description

"last update: 10 June 2024"

- Acknowledgements

Chief Editor: Reda Kamel1

General Secretary: Ahmed Ragab2

General Coordinator: Baliegh Hamdy3

Scientific Board: Ashraf Khaled,4 Mohamed Ghonaim,5 Mahmoud Abdel Aziz,6 Tarek Ghanoum,7 Mahmoud Yousef8

Phoniatrics Manager: Mahmoud Youssef8

Phoniatrics Executive Manager: Dalia Mostafa9

Assembly Board: Safaa Refaat El-Sady,8 Azza Abdel-Aziz Azzam,10Omayma Elsayed Afsah,11Aisha Fawzy Abdel Hady9

Grading Board (In alphabetical order): Amal Saeed,12Aisha Fawzy,9Azza Abdel-Aziz Azzam,10Dalia Mostafa,9 Hemmat Baz,11Nirvana Gamal ElDin Hafez,8Omayma Afsah,11SafaaEl-Sady,8Salwa Ahmed13

Reviewing Board: Alia Mahmoud Elshobary8, Sahar Saad Shohdi9, Azza Samy10, Minrva Eskander14, Shimaa Reffat 15, Sameh Nazmy 16.

1Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Cairo University,2Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Menoufia University,3Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Minia University,4Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/ Beni-Suef University,5Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Tanta University,6Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Mansoura University,7Audiovestibular Unit, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Cairo University, 8Phoniatrics Unit, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Ain Shams University,9Phoniatrics Unit, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Cairo University,10Phoniatrics Unit, Hearing and Speech Institute,11Phoniatrics Unit Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Mansoura University,12Phoniatrics Unit, Otorhino-laryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Zagazig University,13Phoniatrics Unit, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Faculty of Medicine/Benha University. 14 National Institute for Neuro-Motor System. 15 Department of Physical Therapy for Pediatrics, Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University, 16Otolaryngology Department, Hearing and Speech institute.

Sincere thanks extend to the secretaries: Samar Hussein and Eman Ragab, as well as the editor: Mohamed Salah

Other specialties related to the guideline:

Audiology

Otolaryngology

Paediatrics

Neurology

Radiology

Child psychiatry

Orthopaedics

Physiotherapy

Occupational therapy

- Abbreviations

- BDMH Brain damage motor handicap

- CP Cerebral Palsy

- MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- VFSS Video fluoroscopic Swallow Study

- FEES Endoscopic evaluation of swallowing

- NICU Neonatal intensive care unit"

- NMES Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- AAC Alternative systems of communication

- DEXA scan Dual X-ray absorptiometry

- IQ Intelligence Quotient

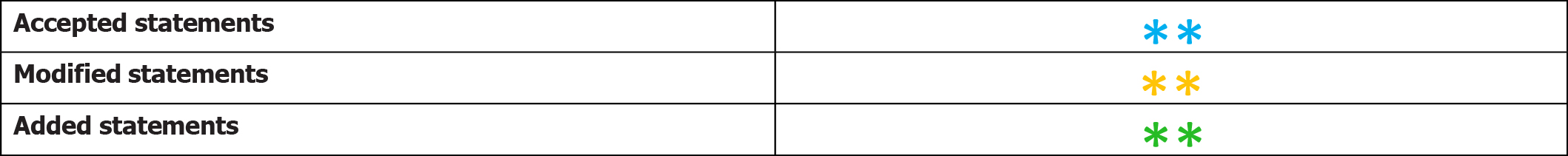

- Executive Summary

1- Assessment of the child with BDMH (CP):

A. Elementary diagnostic procedures:

Through history taking and clinical examination (including vocal tract and neurological examination):

◽ Exclude progressive neurological disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases.

◽ Exclude non-specific motoric insults causing diffuse brain damage (global developmental delay/intellectual disability).

◽ Establish the presence of specific motoric insult.

◽ Determine the type of BDMH (CP) whether spastic, ataxic, dyskinetic, or atonic. (Strong recommendation)

B. Clinical diagnostic aids: including

◽ Psychometric evaluation to determine IQ, mental age, and social age.

◽ Language assessment by standardized Arabic language test to determine receptive, expressive, and total language ages.

◽ Speech assessment for associated dysarthria.

◽ Swallowing assessment for associated feeding and swallowing disorders including instrumental evaluation if needed. (Strong recommendation)

C. Additional instrumental measures: including

◽ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): to investigate etiology in a child or young person with suspected or known BDMH if this is not clear from history or clinical examination.

◽ Audiometry: Initial baseline and regular ongoing hearing assessment are necessary.

◽ Electroencephalogram (EEG): Since epilepsy occurs in around 1 in 3 children with BDMH (CP).

◽ Ophthalmological examination: Initial baseline and regular ongoing visual assessment are necessary. (Strong recommendation)

2- Management of the child with BDMH (CP) through multidisciplinary team approach:

◽ Phoniatric role:

1- Management of language, speech, and communication difficulties: through language and speech therapies that are tailored according to the child’s deficits.

2- Management of feeding and swallowing problems and saliva control: after selection of the appropriate therapy option.

◽ Management of co-morbidities by other team members e.g. neurologist, audiologist, physical therapist, etc. (Strong recommendation)

- Introduction, scope and audience

➡️Introduction

➡️Scope:

The scope of this guideline is the proper diagnosis & management of BDMH/CP and associated co morbidities.

➡️Target audience:

Phoniatricians- neurologists- pediatricians -physiotherapists- dietitian, lactation consultant (infants), occupational therapist, neonatologist, otolaryngologist, gastroenterologist- physical therapist

- Methods

➡️Methods of development

Stakeholder Involvement: Individuals who were involved in the development process. Included the above-mentioned phoniatrics Chief Manager, phoniatrics Executive Manager, Assembly Board, Grading Board and Reviewing Board.

Information about target population experiences was not applicable for this topic.

➡️Search Method

Electronic database searched: Pubmed, Google Scholar, Egyptian Knowledge Bank, Medscape.

➡️Keywords

Cerebral palsy, Brain damage, Guideline, Children

The adaptation cycle passed over: set-up phase, adaptation phase (Search and screen, assessment: currency, content, quality&/decision/selection) and finalization phase that included revision and external reviewing.

➡️Time period searched: from 2010 till 2021

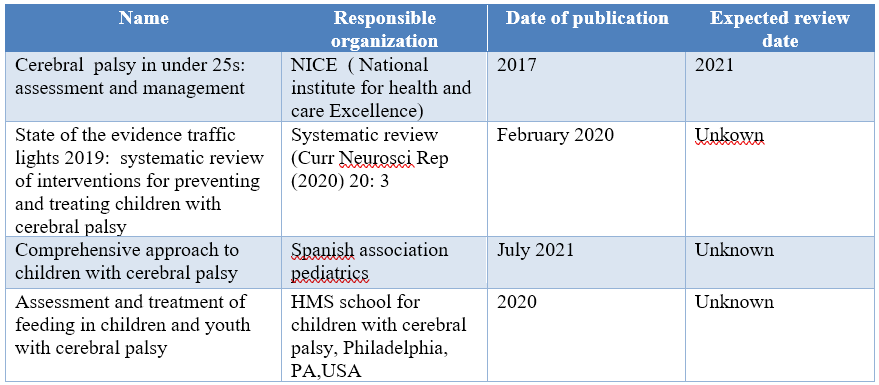

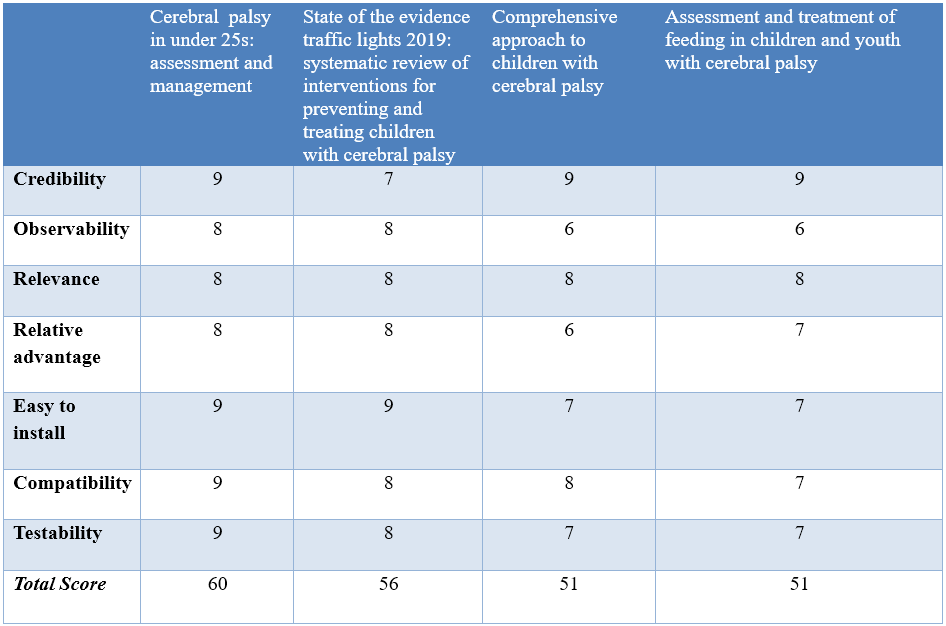

➡️Results

- Four national phoniatricians reviewed the guidelines available

- Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management (NICE, 2017)2 gained the highest scores as regards currency, content and quality and were thus adopted then adapted

- It was graded by 9 expert reviewers' experts and reviewed by 6 expert reviewers to improve quality, gather feedback on draft recommendations.

- The external review was done through a rating scale as well as open-ended questions.

➡️Setting: Primary, secondary and tertiary care centers & hospitals, and related specialties.

Interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations for an intervention (World Health Organization, 2014)

|

Audience |

Strong recommendation |

Conditional recommendation |

|

Patients |

Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action; only a small proportion would not. Formal decision aides are not likely to be needed to help individuals make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. |

Most individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not |

|

Clinicians |

Most individuals should receive the intervention. Adherence to the recommendation could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. |

Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients, who will require assistance in arriving at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Decision aides may be useful in helping individuals make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. |

|

Policymakers |

The recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. |

Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. |

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to Decision frameworks (GRADE Working Group, 2013)

|

Grade |

Definition |

|

High

|

We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

|

Moderate

|

We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

|

Low

|

Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

|

Very Low

|

We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

- Recommendations

The following statements and flowchart were adapted from the Guideline (Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management) which received the highest scores as regards the currency, contents, and quality.

Recommendations statements

|

Clinical question |

Action Recommendation |

Evidence Quality |

Strength of recommendation |

Study type |

Reference |

|

1- Identifying the etiological factors

|

Common risk factors include: Antenatal factors: preterm birth, chorioamnionitis, maternal respiratory tract or genito-urinary infection treated in hospital. Perinatal factors: low birth weight, chorioamnionitis, neonatal encephalopathy, neonatal sepsis (particularly with a birth weight below 1.5 kg), maternal respiratory tract or genito-urinary infection treated in hospital. Postnatal factors: meningitis, jaundice, gastroenteritis with electrolytes imbalance. Abd Elmagid and Magdy (2021) reported that, in Egypt, the perinatal risk factors were more predominant representing 30.5%. The antenatal risk factors represented 21%, the postnatal represented 17.1%, whereas no reliable risk factor could be established in 31.1% of cases. |

high |

Strong recommendation |

Prospective cohort (3), systematic review and meta-analysis (4), retrospective cohort (5) |

3, 4, 5 |

|

2- Pathology of BDMH (CP)

|

MRI-identified brain abnormalities have been reported at the following approximate prevalence in children with BDMH (CP): white matter damage: 45%, basal ganglia or deep grey matter damage: 13%, congenital malformation: 10%, focal infarcts: 7%. - White matter damage, including periventricular leukomalacia shown on neuroimaging is more common in children born preterm than in those born at term, may occur in children with any functional level or motor subtype, but is more common in spastic than in dyskinetic BDMH (CP). - Basal ganglia or deep grey matter damage is mostly associated with dyskinetic BDMH (CP). -Congenital malformations as a cause of BDMH(CP) are more common in children born at term than in those born preterm, may occur in children with any functional level or motor subtype, and are associated with higher levels of functional impairment than other causes. - The clinical syndrome of neonatal encephalopathy can result from various pathological events, such as a hypoxic–ischaemic brain injury or sepsis, and if there has been more than 1 such event they may interact to damage the developing brain. -Neonatal encephalopathy has been reported at the following approximate prevalence inchildren with BDMH (CP) born after 35 weeks: § Attributed to a perinatal hypoxic–ischaemic injury: 20%. § Not attributed to a perinatal hypoxic–ischaemic injury: 12%. - In cases of BDMH (CP) associated with a perinatal hypoxic–ischaemic injury: the extent of long-term functional impairment is often related to the severity of the initial encephalopathy &the dyskinetic motor subtype is more common than other subtypes. -BDMH(CP) acquired after the neonatal period, the following causes and approximate prevalence have been reported: meningitis: 20% , other infections: 30% &head injury: 12%. -The independent risk factors can have a cumulative impact, adversely affecting the developing brain and resulting in BDMH(CP), may have an impact at any stage of development, including the antenatal, perinatal and postnatal periods. |

high |

Strong recmmendation |

Systematic review |

6 |

|

3- The need for MRI |

-Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is needed to investigate etiology in a child or young person with suspected or known BDMH if this is not clear fromhistory or clinical examination. -When MRI is recommended, the following factors will be put into account: ▪️ Subtle neuro-anatomical changes that could explain the etiology of BDMH (CP) may not be apparent until 2 years of age. ▪️ The presence of any red flags for a progressive neurological disorder. |

low |

Strong recommendation |

Cohort |

7 |

|

4- Clinical & Developmental Manifestations of BDMH(CP) |

*Provide an enhanced clinical and developmental follow-up program by a multidisciplinary team for children up to 2 years (corrected for gestational age) who are at increased risk of developing BDMH(CP). * Early signs include; -Unusual fidgety movements or other abnormalities of movement, including asymmetry or paucity of movement. -Abnormalities of tone, including hypotonia (floppiness), spasticity (stiffness) or dystonia (fluctuating tone). -Abnormal motor development including late head control, rolling and crawling. -Feeding difficulties. *Recognize that the most common delayed motor milestones in children with BDMH(CP) are: -Not sitting by 8 months (corrected for gestational age). -Not walking by 18 months (corrected for gestational age). -Early asymmetry of hand function (hand preference) before 1 year (corrected for gestational age). |

low |

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

8,9 |

|

5-Red flags for other neurological disorders

|

Recognize the following as red flags for neurological disorders other than BDMH (CP), and refer the child or young person to a specialist in pediatric neurology if any of these are observed: · Absence of known risk factors. · Family history of a progressive neurological disorder. · Loss of already attained cognitive or developmental abilities. · Development of unexpected focal neurological signs. · MRI findings suggestive of a progressive neurological disorder. · MRI findings not in keeping with clinical signs of BDMH. |

Very low |

Strong recommendation |

Expert opinion |

10 |

|

6- The need for multidisciplinary team

|

-Ensure that the child or young person with BDMH(CP) has access to a local integrated core multidisciplinary team: ▪️ Pediatric or adult medicine ▪️ Nursing care ▪️ Physiotherapy ▪️ Occupational therapy ▪️ Speech and language therapy ▪️ Dietetics ▪️ Psychology § Pediatric or adult neurodisability, neurology, neurorehabilitation, respiratory, gastroenterology and surgical specialist care ▪️ Orthopedics ▪️ Orthotics and rehabilitation services ▪️ Social care ▪️ Visual and hearing specialist services ▪️Teaching support for preschool and school-age children, including portage (home teaching services for preschool children). -Recognize that ongoing communication between all levels of service provision in the care of children and young people with BDMH (CP) is crucial, particularly involvement of primary care from diagnosis onwards. |

low |

Strong recommendation |

Cohort |

11 |

|

7- Providing information and support

|

Provide clear, timely and up-to-date information to parents or careers on the following topics: diagnosis, etiology, prognosis, expected developmental progress, comorbidities , availability of specialist equipment, resources available and access to financial, respite, social care and other support for children and young people and their parents, carers and siblings, educational placement (including specialist preschool and early years settings). |

moderate |

Strong recommendation |

Qualitative semistructured |

12 |

|

8-Providing information about prognosis

|

-The more severe the child's physical, functional or cognitive impairment, the greater the possibility of difficulties with walking. -If a child can sit at 2 years of age it is likely, but not certain, that they will be able to walk unaided by age 6. -If a child cannot sit but can roll at 2 years of age, there is a possibility that they may be able to walk unaided by age 6. -If a child cannot sit or roll at 2 years of age, they are unlikely to be able to walk unaided. -Recognize the following in relation to prognosis for speech development in a child with BDMH, and discuss this with parents or carers as appropriate: Around 1 in 2 children with BDMH(CP) have some difficulty with elements of communication: -Around 1 in 3 children have specific difficulties with speech and language. -The more severe the child's physical, functional or cognitive impairment, the greater the likelihood of difficulties with speech and language. -Uncontrolled epilepsy may be associated with difficulties with all forms of communication, including speech. -A child with bilateral spastic, dyskinetic or ataxic BDMH(CP) is more likely to have difficulties with speech and language than a child with unilateral spastic BDMH(CP). -The more severe the child's physical, functional or cognitive impairment, the greater the likelihood of reduced life expectancy. -There is an association between reduced life expectancy and the need for enteral tube feeding, but this reflects the severity of swallowing difficulties and is not because of the intervention. |

low

|

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

13, 14 |

|

9-Using MRI for prognosis

|

Do not rely on MRI alone for predicting prognosis in children with BDMH(CP). |

low |

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

15 |

|

10-Assessment of Eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties

|

Half of all children with BDMH (CP) have dysphagia and the prevalence is even higher in the infant population. Dysphagia management is extremely important because aspiration resulting in respiratory complication is a leading cause of death in individuals with BDMH (CP) (45%). The type of oral and pharyngeal problems in children with BDMH (CP) include reduced lip closure, poor tongue function, tongue thrust, exaggerated bite reflex, tactile hypersensitivity, delayed swallow initiation, reduced pharyngeal mobility & drooling. -Red flags for feeding/swallowing problems in children with BDMH(CP) are: · A feeding time of > 30 min on a regular basis. · Lack of weight gain for 2–3 months, not just weight loss particularly in the first 2 years of life. · Stressful mealtimes to the child or parents. · Increased congestion at meal times, gurgly voice quality, history of respiratory illnesses. -A team approach is necessary for diagnosing and managing pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. In addition to the phoniatrician, team members may include family and/or caregivers, dietitian, lactation consultant (infants), occupational therapist, physician (e.g., pediatrician, neonatologist, otolaryngologist, gastroenterologist), physical therapist, psychologist, social worker Assessment of infants and young children with signs and symptoms of feeding and/or swallowing disorders is likely to encompass multiple dimensions that include, but may not be limited to: (a) Review of family, medical, developmental, and feeding history. (b) Clinical Feeding and Swallowing Assessment: This typically consists of a physical examination (prefeeding assessment),oral structure and function examination, and feeding observation. (c) Other considerations (e.g., somatic growth patterns, neurodevelopmental status, orofacial structures, cardiopulmonary, and other GI function). (d) Instrumental swallowing evaluation. Criteria for an instrumental swallowing study in children with BDMH include the following: (1) Risk of aspiration (by history or observation), (2) Prior aspiration pneumonia, (3) Suspicion of a pharyngeal or laryngeal problem (forexample, breathy voice quality), 4) Gurgly voice quality. A videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS) provides dynamic visualization of oral, pharyngeal and upper esophageal phases of swallowing. A flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) allows direct visualization of some aspects of the pharyngeal phase. |

Very low |

Strong recommendation |

Literature review |

16 |

|

11-Management of Eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties

|

-Treatment selection will depend on the child’s age, cognitive and physical abilities, and specific swallowing and feeding problems 1-Postural and Positioning Techniques These techniques serve to protect the airway and offer safer transit of food and liquid. Techniques include chin down, chin up, head rotation, upright positioning (90° angle at hips and knees, feet on floor, with supports as needed), head stabilization (supported so as to present in chin-neutral position), cheek and jaw assist, reclining position, and side-lying positioning for infants. 2- Diet Modifications Typical modifications may include thickening thin liquids, softening, cutting/chopping, or pureeing solid foods to facilitate safety and ease of swallowing. Taste or temperature of a food may be altered to provide additional sensory input for swallowing 3-Adaptive Equipment and Utensils These may be used with children who have feeding problems to foster independence with eating and increase swallow safety by controlling bolus size or achieving the optimal flow rate of liquids. Examples include modified nipples, cut out cups, angled forks and spoons, and sectioned plates. 4- Maneuvers Maneuvers are strategies used to change the timing or strength of movements of swallowing. Examples of maneuvers include Effortful swallow, Masako, or tongue hold, Mendelsohn maneuver, Supraglottic swallow, Super-supraglottic swallow. 5- Oral–Motor Treatments Oral–motor treatments include stimulation to—or actions of—the lips, jaw, tongue, soft palate, pharynx, larynx, and respiratory muscles. Oral–motor treatments range from passive (e.g., tapping, stroking, and vibration) to active (e.g., range-of-motion activities, resistance exercises, or chewing and swallowing exercises). Oral–motor treatments are intended to influence the physiologic underpinnings of the oropharyngeal mechanism in order to improve its functions. Some of these interventions can also incorporate sensory stimulation. 6- Feeding Strategies Feeding strategies include pacing and cue-based feeding. Pacing: Feeding strategies for children may include alternating bites of food with sips of liquid or swallowing 2–3 times per bite or sip. For infants, pacing can be accomplished by limiting the number of consecutive sucks. Strategies that slow the feeding rate may allow for more time between swallows to clear the bolus and may support more timely breaths. Cue-based feeding: Most neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) have begun to move away from volume-driven feeding to cue-based feeding. In the NICU, the phoniatrician plays a critical role, supporting parents and other caregivers to understand and respond accordingly to the infant's communication during feeding. 7-Sensory Stimulation Techniques These may include thermal–tactile stimulation (e.g., using an iced lemon glycerin swab) or tactile stimulation (e.g., using a NUK brush) applied to the tongue or around the mouth. Sensory stimulation may be needed for children with reduced responses, overactive responses, or limited opportunities for sensory experiences. 8- Behavioral Interventions They are based on principles of behavioral modification and focus on increasing appropriate actions or behaviors and reducing maladaptive behaviors related to feeding. Examples include antecedent manipulation, shaping, prompting, modeling, stimulus fading, and differential reinforcement of alternate behavior, as well as implementation of basic mealtime principles (e.g., scheduled mealtimes in a neutral atmosphere with no food rewards). 9- Tube Feeding such as nasogastric tube, and gastrostomy. These approaches may be considered if the child’s swallowing safety and efficiency cannot reach a level of adequate function or does not adequately support nutrition and hydration. Non-nutritive sucking opportunities are thought to facilitate oral feeding skills in infants, most often via Pacifier. Children receiving nutrition and hydration via tube should be appropriate for brief ‘taste’ sessions over2–5 min multiple times per day. Spoon presentations with two to three drops of lemon juice or ice water may be tolerated without compromising pulmonary status and help to stimulate swallowing. Regular and thorough oral care is vital for all children. 10- Oral appliances or feeding devices 11-Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) |

Very low

|

Strong recommendation |

Literature review |

17 |

|

12- Managing saliva control |

- The reported prevalence of drooling ranges from 10% to 58%. In the assessment of affected patients, clinicians should determine its frequency, severity and impact on the quality of life of children and their caregivers. -A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of drooling is advisable. -Treatment Options: 1- Behavioral interventions: The aim of these interventions is to increase target behaviors, such as swallowing saliva, wiping lips and chin, improving head control, and teaching ways to manage drooling independently. Treatment techniques can include: instruction (e.g. please wipe your chin), prompting (e.g. giving a verbal prompt to swallow), positive reinforcement (e.g. praise), and/or self-management (instructions to swallow and wipe the chin) 2- Physical, oro-motor and oro-sensory therapies: These interventions involve correction of general body posture and head posture to eliminate the anterior loss of saliva from the oral cavity, therapy to improve lip and jaw closure as well as increasing tongue control, reducing tongue thrust , normalizing tone, and normalizing facial and oral sensation. 3- Pharmacologic treatments e.g. anticholinergic drugs 4-Botulinum toxin A injections to the salivary glands with ultrasound guidance if anticholinergic drugs provide insufficient benefit or are not tolerated. 5- Surgical interventions e.g. salivary gland excision, ligation, duct rerouting. 6- Intra-oral appliances e.g. the Exeter Lip Sensor, palatal training appliances. |

High

|

Strong recommendation |

randomised controlled trial |

18 |

|

13- Language and communication |

-Communication difficulties are common in BDMH (CP) and are frequently associated with motor, intellectual and sensory impairments. -BDMH (CP) is an umbrella term referring to non-progressive motor disorders that arise from damage to the fetal or infant brain. Children with BDMH (CP) often have limitations in cognition, sensation, communication, and eating and drinking. -Young people with BDMH (CP) whohave communication difficulties frequently experience more limited participation in social, educational and community life and have lower perceived quality of life than their peers without communication limitations, including those with BDMH (CP), putting them at severe risk of educational failure and later unemployment. Language Around 48% of children with BDMH (CP) have cognitive impairments, which range in severity from mild to profound. Current research suggests that language difficulties in BDMH (CP) are associated with poor nonverbal cognitive development rather than comprising specific impairments of language processing. Such research should examine receptive and expressive language and semantics as well as syntax, as lack of experience of the world due to mobility restriction may limit vocabulary. Children with restricted upper limb control may have problems manipulating toys in early language tests. Children with visual impairments may find it difficult to scan and discriminate between small line drawings. The underlying causes of language delay may be attributed to associated factors such as sensory impairment as hearing & visual impairment in addition to environmental deprivation and lack of language stimulation. Literacy Written language problems of children with BDMH (CP), in both reading and spelling are associated with nonverbal cognition, speech and working memory impairments. Reading interventions for children with severe speech impairment who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) focus on adapting the literacy environment and increasing opportunities for children to participate in literacy activities. At least 1 in 10 need augmentative and alternative communication (signs, symbols and speech generating devices). Around 1 in 10 cannot use formal methods of augmentative and alternative communication because of cognitive and sensory impairments and communication difficulties. |

low

|

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

19 |

|

14-Communication intervention

|

The goal of communication therapy for children is to become active and independent Communicators in all of their daily environments. A review of the evidence for language interventions showed that experimental studies exist to support intervention for vocabulary, grammar, narrative and social use of language. But, as with test materials, interventions may need to be adapted to meet the individual needs of children with restricted speech and movement and the impact of such adaptations on cognitive processing must be considered. To do this they need to develop as full a range of communication skills as possible and to have an Intelligible means of expressing all their needs and ideas. The hearing problem should be assessed for the need of hearing aids and cochlear implant according to the profile of each CP case. Children whose speech is often unintelligible may require augmentative and alternative systems of communication (AAC) to supplement their natural modes. The aim of AAC is to provide children all the vocabulary they need to communicate independently. AAC should be linked to verbal output from the conversational partner. |

low

|

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

20 |

|

15-Speech Manifestations

|

Dysarthria in BDMH(CP) commonly affects all aspects of speech production: respiration, phonation, resonance, articulation and prosody. Impairments include: shallow, irregular breathing for speech; low pitched, harsh voice; reduced pitch variation/unexpected pitch breaks; hyper-nasality; and poor articulation. Although the underlying motor disorders vary (spasticity is associated with increased tone and reduced range of movement, choreo-athetosis is associated with involuntary movement and dysrhythmia), most characteristics (low pitch, poor breath control, imprecise articulation) affect the speech of children with both spastic and dyskinetic BDMH(CP) in addition to the cerebellar (with slowing down of articulatory movements, affected prosody with increased variability of pitch and loudness in addition to increased & equal stress) and mixed dysarthric types. The dyskinetic type is usually associated with severe degree of dysarthria up to anarthria due to the associated involuntary movements of the vocal tract. |

Very low |

Strong recommendation |

Literature review |

21 |

|

16-Intervention for speech impairment

|

Physiological approaches focusing on respiratory support and speech rate, which follow motor learning principles, show promise for children and young people with BDMH (CP). PROMPT (Program for Restructuring Oral Musculature Phonetic Targets), a sensory-motor therapy in which therapists provide auditory, visual, tactile and kinesthetic cues for the production of speech sounds, help changes in lip and jaw control and gains improvement in intelligibility Articulation therapy is not generally advised as a first line of treatment, due to the impaired control of multiple speech subsystems in BDMH dysarthria and the need for breath support to create clear vocal signal. Oral motor therapy is widely used for improving chewing, swallowing and salivary control associated with dysarthria. Careful application of articulation therapy techniques according to the dysarthric manifestations of the BDMH (CP) children. Syllable by syllable attack and multisyllabic segmentation are appropriate for spastic dysarthria rather than dyskinetic& cerebellar dysarthria that might get benefit from other techniques like soft articulatory contact and modeling respectively. |

Very low

|

Strong recommendation |

Literature review |

21 |

|

17-Low bone mineral density |

Risk factors: -Recognize that in children and young people with BDMH(CP) the following are independent risk factors for low bone mineral density: · Non-ambulant. · Vitamin D deficiency. · Presence of eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties or concerns about nutritional status. · Low weight for age (below the 2nd centile). · History of low-impact fracture. · Use of anticonvulsant medication. -Inform children and young people with BDMH (CP) and their parents or carers if they are at an increased risk of low-impact fractures (e.g. non-ambulant or have low bone mineral density). Management: -If there are 1 or more risk factors for low bone mineral density: · Assess dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D · Consider the following laboratory investigations: serum calcium, phosphate and alkaline phosphatase serum vitamin D urinary calcium/creatinine ratio. -Create an individualized care plan for children and young people with BDMH (CP) who have 1 or more risk factors for low bone mineral density. -Consider interventions to reduce the risk of reduced bone mineral density and low-impact fractures as dietetic interventions (including nutritional support and calcium and vitamin D supplementation) and minimizing risks associated with movement and handling. -Consider a DEXA scan under specialist guidance for children and young people with BDMH(CP) who have had a low-impact fracture and refer them to a specialist centre for consideration of bisphosphonate therapy. -Do not offer standing frames or vibration therapy solely to prevent low bone mineral density in children and young people with BDMH(CP). |

High

|

Strong recommendation |

Prospective cohort (22), randomised controlled trial (23) |

22, 23 |

|

18- Pain, discomfort and distress |

- Explain to children and young people with cerebral palsy and their parents or careers that pain is common in people with BDMH (CP), especially those with more severe motor impairment, and this should be recognized and addressed. -Recognize that common causes of pain, discomfort and distress in children and young people with BDMH(CP) include: *Musculoskeletal problems (for example, scoliosis, hip subluxation and dislocation). *Increased muscle tone (including dystonia and spasticity). *Muscle fatigue and immobility. *Constipation. *Vomiting. *Gastro-esophageal reflux disease. *Other general causes such as non-specific back pain, headache, non-specific abdominal pain, dental pain, and dysmenorrhea. -Refer the child or young person with BDMH (CP) to a specialist pain multidisciplinary team, for assessment and management. |

moderate

|

Conditional recommendation |

Observational cross-sectional |

24 |

|

19-Sleep disturbances

|

-Explain to parents or carers that, in children and young people with BDMH (CP), sleep disturbances are common and may be caused by factors such as environment, hunger and thirst. -Recognize that the most common condition-specific causes of sleep disturbances in children and young people with BDMH(CP) include: *Breathing disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea. *Seizures. *Pain and discomfort. *Need for repositioning because of immobility. *Poor sleep hygiene (poor night-time routine and environment). *Night-time interventions, including overnight tube feeding or the use of orthoses. *Comorbidities, including adverse effects of medication. |

moderate

|

Strong recommendation |

Observational cross-sectional |

25 |

|

20- Mental health problems

|

Identification: -Recognize that children and young people with BDMH(CP) have an increased prevalence of mental health and psychological problems (including depression, anxiety and conduct disorders) -Recognize that emotional and behavioral difficulties (for example, low self-esteem) are reported in up to 1 in 4 children and young people with BDMH (CP) and that their assessment can be challenging in children and young people with communication difficulties or intellectual disability. -Think about and address the following contributory factors if a change in emotional state occurs in a child or young person with CP: *Pain or discomfort. *Frustration associated with communication difficulties. *Social factors, such as a change in home circumstances or care provision. Management: Refer the child or young person with BDMH (CP) for specialist psychological assessment and ongoing management if emotional and behavioral difficulties persist or there are concerns about their mental health. |

low

|

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

26 |

|

21- Registering and processing sensory information

|

-Explain to children and young people with BDMH (CP) and their parents that difficulties with learning and movement may be exacerbated by difficulties with registering or processing sensory information, which may include: *Primary sensory disorders in any of the sensory systems (for example, difficulties with depth perception may affect the ability to walk on stairs), *Disorders of sensory processing and perception, such as planning movements or being able to concentrate and pay attention. -Explain to parents or carers that there is a lack of evidence to support specific interventions. |

High

|

Conditional recommendation |

Randomised controlled trials |

27, 28 |

|

22- Information on other comorbidities: a) Visual impairment

|

-Refer all children with BDMH(CP) for an initial baseline ophthalmological assessment at the time of diagnosis as: * 1 in 2 children and young people with BDMH (CP) will have some form of visual impairment. * Prevalence of visual impairment increases with increasing severity of motor impairment. *Visual problems may include; controlling eye movements, strabismus (squint), refractive errors, problems of eye function, including retinopathy of prematurity, impaired visual processing, and visual field defects. -Regular ongoing vision assessment is necessary. |

low

|

strong recommendation |

cohort |

29 |

|

b) Hearing impairment

|

Discuss the following information: • Hearing impairment occurs in around 1 in 10 children and young people with BDMH (CP). • Prevalence of hearing impairment increases with increasing severity of motor impairment. • It is more common in people with dyskinetic or ataxic BDMH (CP) than in those with spastic BDMH (CP). • Regular ongoing hearing assessment is necessary & intervention with the use of hearing aids or cochlear implant should be discussed with the parents/ caregivers according to the profile of each patient. |

low |

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

29 |

|

c) Intellectual disability

|

- Discuss the following: • Intellectual Disability (IQ below 70) occurs in around 1 in 2 children and young people with BDMH(CP). • Severe intellectual disability (IQ below 50) occurs in around 1 in 4 children and young people with BDMH(CP). • Intellectual disability increases with increasing severity of motor impairment. |

low |

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

29 |

|

d) Behavioral difficulties

|

- Discuss the following: 2 to 3 in 10 children and young people with BDMH(CP) have 1 or more of the following: • Emotional and behavioral difficulties affecting function and participation. • Problems with peer relationships. • Difficulties with attention, concentration and hyperactivity. • Conduct behavioral difficulties. -Limited processing sensory information may present as behavioral difficulties. - Manage routine behavioral difficulties within the multidisciplinary team, and refer psychiatrist if difficulties persist. |

moderate |

Conditional recommendation |

Observational cross-sectional |

30 |

|

e) Epilepsy

|

-Epilepsy occurs in around 1 in 3 children with BDMH(CP) and 1 in 2 children with dyskinetic BDMH(CP). Dyskinetic movements should not be misinterpreted as epilepsy. -The seizures include focal, generalized & combined. -Diagnosis depends on family & personal history, characteristics of clinical events with electroencephalogram used as a gold standard. |

low |

Strong recommendation |

cohort |

29 |

|

f) Motoric problems

|

The patient should be referred to the physiotherapist to assess the motoric condition Multiple techniques will be discussed with the parents including: -Bobath (neurodevelopmental approach) technique: it is multidisciplinary approach, involving physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech language therapists. -Roods approach (neuro- physiological approach) dealing with the activation and de-activation of sensory receptors, which is concerned with the interaction of somatic, autonomic and psychic factors and their role in regulation of motor behavior. |

Very low |

Conditional recommendation |

Literature review |

1 |

|

g) Vomiting, regurgitation and reflux

|

Advise parents that these symptoms are common in children and young people with BDMH(CP). If there is a marked change in the pattern of vomiting, assess for a clinical cause. |

Very low |

Conditional recommendation |

Literature review |

31 |

|

h) Constipation

|

-3 in 5 children and young people with BDMH(CP) have chronic constipation. -Regular clinical assessment for constipation is necessary. |

Very low |

Conditional recommendation |

Literature review |

31 |

|

23- Care needs

|

-Recognize the importance of social care needs in facilitating participation and independent living for children and young people with BDMH (CP). - Discuss the following: • Social care services • Financial support, welfare rights and voluntary organizations. • Support groups (including psychological and emotional support). • Respite & hospiceservices. - Address points related to: • Mobility. • Equipment, particularly wheelchairs and hoists. • Transport. • Toileting and changing facilities. - Ensure effective communication and integrated team working between health and social care providers.

|

low |

Strong recommendation

|

cohort |

11 |

- Monitoring and evaluating the impact of the guideline

Monitoring/ Auditing Criteria: to assess gridline implementation or adherence to recommendations. This is achieved if the quality of life of BDMH/CP is improved with no increase in rate of complications

Cerebral palsy is not a single disorder but a group of disorders with diverse implications for children and their families.

- Follow up of "at risk" infants, such as those born prematurely

- Delayed motor milestones, particularly learning to sit, stand and walk

- Asymmetric movement patterns, for example, strong hand preference early in life

- Abnormalities of muscle tone particularly spasticity or hypotonia

- Management problems, for example, severe feeding difficulties and unexplained irritability. Many other conditions present with these features.

*Observation of the child often provides more information than 'hands on' examination. Look for the presence or absence of age appropriate motor skills and their quality.

Clinicians should be aware of associated disorders as:

- Visual problems (approximately 40%) e.g. strabismus, refractive errors, visual field defects and cortical visual impairment

- Hearing deficits (approximately 3 - 10%)

- Speech and language problems

- Epilepsy (approximately 50%)

- Cognitive impairments. Intellectual disability, learning problems and perceptual difficulties are common. There is a wide range of intellectual ability and children with severe physical disabilities may have normal intelligence

Management

Management involves a team approach with health professionals and teachers. Input from the family is important.

1. Accurate

diagnosis & Establish the cause of cerebral palsy if possible.

2. Management of the

associated disabilities, health problems and consequences of the motor disorder

- Recognize the following as red flags for neurological disorders other than BDMH (CP), and refer the child or young person to a specialist in pediatric neurology if any of these are observed:

· Absence of known risk factors.

· Family history of a progressive neurological disorder.

· Loss of already attained cognitive or developmental abilities.

· Development of unexpected focal neurological signs.

· MRI findings suggestive of a progressive neurological disorder.

-Working with families

Care of the child with cerebral palsy involves developing a trusting and

cooperative relationship with parents. Parents may need practical support such

as provision of respite care and information about financial allowances

- Updating of the guideline

Updating Procedure:

Any recommendation of this guideline will be updated when new evidence that could potentially impact the current evidence base for this recommendation is identified. If no new reports or information are identified for a particular recommendation, the recommendation will be revalidated. The focus will be on recommendations supported by very-low- or low certainty evidence and where new recommendations or a change in the published recommendations may be needed.

- References

1- Patel D.R., Neelakantan M, Pandher K, Merrick J (2020): Cerebral palsy in children: a clinical overview. Translational Pediatrics; 9(Suppl 1): S125–S135. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.01.01

2- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management. NG62. January 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/ng62

3- Beaino, G., Khoshnood, B., Kaminski, M., Pierrat, V., Marret, S., Matis, J., Ledesert, B., Thiriez, G., Fresson, J., Roze, J. C., Zupan-Simunek, V., Arnaud, C., Burguet, A., Larroque, B., Breart, G., Ancel, P. Y., Epipage Study Group, Predictors of cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE prospective population-based cohort study, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 52, e119-25, 2010

4- Alshaikh, B., Yusuf, K., Sauve, R., Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis, Journal of Perinatology, 33, 558-64, 2013

5- Abd Elmagid D. and Magdy H. (2021): Evaluation of risk factors for cerebral palsy. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery; 57:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00265-1

6- Reid, S.M., Dagia,C.D., Ditchfield,M.R., Carlin,J.B., Reddihough,D.S., Population-based studies of brain imaging patterns in cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 56, 222-232, 2014

7- de Vries, L. S., Eken, P., Groenendaal, F., van Haastert, I. C., Meiners, L. C., Correlation between the degree of periventricular leukomalacia diagnosed using cranial ultrasound and MRI later in infancy in children with cerebral palsy, Neuropediatrics, 24, 263-8, 1993

8- Brogna, C., Romeo, D. M., Cervesi, C., Scrofani, L., Romeo, M. G., Mercuri, E., Guzzetta, A., Prognostic value of the qualitative assessments of general movements in late-preterm infants, Early Human Development, 89, 1063-6, 2013

9- Morgan, C., Crowle, C., Goyen, T. A., Hardman, C., Jackman, M., Novak, I., Badawi, N., Sensitivity and specificity of General Movements Assessment for diagnostic accuracy of detecting cerebral palsy early in an Australian context, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 52, 54-59, 2016

10- Oberklaid F, Drever K. Is my child normal? Milestones/red flags for referral. Aust Family Physician 2011; 40: 666–71..

11- Sukhov, A., Wu, Y., Xing, G., Smith, L. H., Gilbert, W. M., Risk factors associated with cerebral palsy in preterm infants, Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 25, 53-7, 2012

12- Barnfather, A., Stewart, M., Magill-Evans, J., Ray, L., Letourneau, N., Computer-mediated support for adolescents with cerebral palsy or spina bifida, CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29, 24-33, 2011

13- Beckung, E., Hagberg, G., Uldall, P., Cans, C., Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in, Europe, Probability of walking in children with cerebral palsy in Europe, Pediatrics, 121, e187-92, 2008

14- Westbom, L., Bergstrand,L., Wagner,P., Nordmark,E., Survival at 19 years of age in a total population of children and young people with cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53, 808-814, 2011

15- van Kooij, B. J., van Handel, M., Nievelstein, R. A., Groenendaal, F., Jongmans, M. J., de Vries, L. S., Serial MRI and neurodevelopmental outcome in 9- to 10-year-old children with neonatal encephalopathy, Journal of Pediatrics, 157, 221-227.e2, 2010

16- Arvedson J. C. (2013).Feeding children with cerebral palsy and swallowing difficulties. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition;67, S9–S12

17- Arvedson J. C . (1998): Management of Pediatric Dysphagia. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America; 31 (3) : 453-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-6665(05)70064-5

18- Sethy D., Mokashi S., Effect of a token economy behaviour therapy on drooling in children with cerebral palsy, International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 18, 494-499, 2011

19- Pennington, Lindsay & Dave, Mona & Rudd, Jennifer & Hidecker, Mary Jo Cooley & Caynes, Katy & Pearce, Mark. (2020). Communication disorders in young children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 62. 10.1111/dmcn.14635.

20- Watson, R M & Pennington, L .Assessment and management of the communication difficulties of children with cerebral palsy: a UK survey of SLT practice. International journal of language & communication disorders. 50(2), 2015

21- Pennington, L. Speech and communication in cerebral palsy. Eastern J Med. 2012; 17(4): 171-177

22- Jekovec-Vrhovsek, M., Kocijancic, A., Prezelj, J., Effect of vitamin D and calcium on bone mineral density in children with CP and epilepsy in full-time care, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 42, 403-5, 2000

23- Ruck, J., Chabot, G., Rauch, F., Vibration treatment in cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled pilot study, Journal of Musculoskeletal Neuronal Interactions, 10, 77-83, 2010

24- Alriksson-Schmidt, A., Hagglund, G., Pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a population-based registry study, Acta Paediatrica, 105, 665-70, 2016

25- Adiga, D., Gupta, A., Khanna, M., Taly, A. B., Thennarasu, K., Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy and its correlation with sleep disturbance in primary caregivers and other associated factors, Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 17, 473-6, 2014

26- Bjorgaas, H.M., Elgen, I., Boe, T., Hysing, M., Mental health in children with cerebral palsy: does screening capture the complexity?, The scientific world journal, 2013, 468402-, 2013

27- James, S., Ziviani, J., Ware, R. S., Boyd, R. N., Randomized controlled trial of web-based multimodal therapy for unilateral cerebral palsy to improve occupational performance, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57, 530-8, 2015

28- Kuo, H. C., Gordon, A. M., Henrionnet, A., Hautfenne, S., Friel, K. M., Bleyenheuft, Y., The effects of intensive bimanual training with and without tactile training on tactile function in children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy: A pilot study, Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49, 129-39, 2016

29- Delacy, M. J., Reid, S. M., Australian cerebral palsy register, group, Profile of associated impairments at age 5 years in Australia by cerebral palsy subtype and Gross Motor Function Classification System level for birth years 1996 to 2005, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 58 Suppl 2, 50-6, 2016

30- Parkes, J., White-Koning,M., Dickinson,H.O., Thyen,U., Arnaud,C., Beckung,E., Fauconnier,J., Marcelli,M., McManus,V., Michelsen,S.I., Parkinson,K., Colver,A., Psychological problems in children with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional European study, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 49, 405-413, 2008

31- Odding, E., Roebroeck, M. E., Stam, H. J., The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: Incidence, impairments and risk factors, Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 183-191, 2006

- Further Reading

• World Health Organization (2014): WHO handbook for guideline development – 2nd ed. Chapter 10, page 129 (ISBN 978 92 4 154896 0)

• Schünemann, Brożek, Guyatt, Oxman GRADE Handbook, Chapter 5; Quality of evidence, 2013- Annexes

Editorial Independence:

· This guideline was developed without any external funding.

· All the guideline development group members have declared that they do not have any competing interests.

Annex 1: Guideline Flowchart

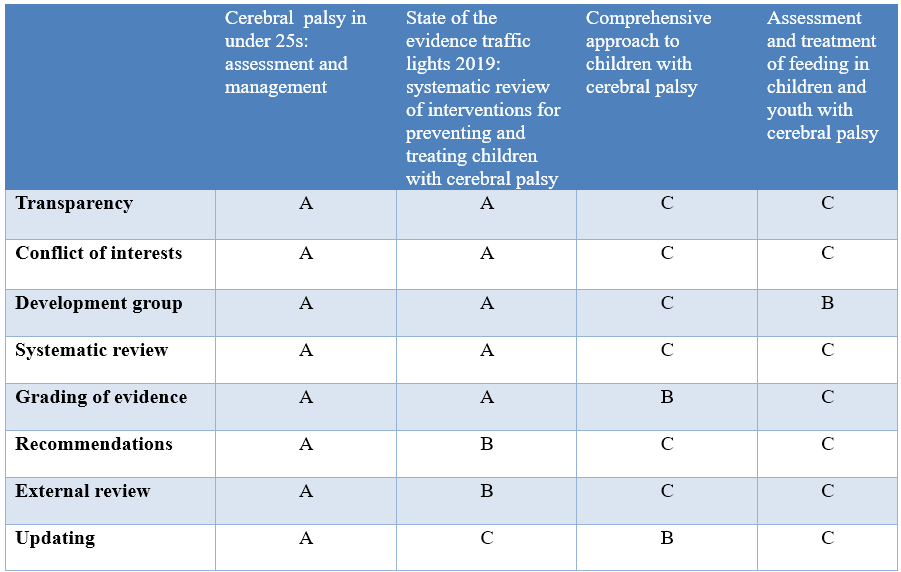

Annex 2: Tables of appraisal of selected guidelines:,

Currency (table 1)

Content (table 2)

Quality (table 3)

Annex 3: The risks and benefits of added and/or modified statements

|

STATEMENT |

RISK |

BENEFIT |

|

Assessment of Eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties Half of all children with BDMH (CP) have dysphagia and the prevalence is even higher in the infant population. Dysphagia management is extremely important because aspiration resulting in respiratory complication is a leading cause of death in individuals with BDMH (CP) (45%). The type of oral and pharyngeal problems in children with BDMH (CP) include reduced lip closure, poor tongue function, tongue thrust, exaggerated bite reflex, tactile hypersensitivity, delayed swallow initiation, reduced pharyngeal mobility & drooling. -Red flags for feeding/swallowing problems in children with BDMH(CP) are: · A feeding time of > 30 min on a regular basis. · Lack of weight gain for 2–3 months, not just weight loss particularly in the first 2 years of life. · Stressful mealtimes to the child or parents. · Increased congestion at mealtimes, gurgly voice quality, history of respiratory illnesses.

-A team approach is necessary for diagnosing and managing pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. In addition to the phoniatrician, team members may include family and/or caregivers, dietitian, lactation consultant (infants), occupational therapist, physician (e.g., pediatrician, neonatologist, otolaryngologist, gastroenterologist), physical therapist, psychologist, social worker Assessment of infants and young children with signs and symptoms of feeding and/or swallowing disorders is likely to encompass multiple dimensions that include, but may not be limited to: (a) Review of family, medical, developmental, and feeding history. (b) Clinical Feeding and Swallowing Assessment: This typically consists of a physical examination (pre feeding assessment),oral structure and function examination, and feeding observation. (c) Other considerations (e.g., somatic growth patterns, neuro developmental status, oro facial structures, cardio pulmonary and other GI function). (d) Instrumental swallowing evaluation.

Criteria for an instrumental swallowing study in children with BDMH include the following: (1) Risk of aspiration (by history or observation), (2) Prior aspiration pneumonia, (3) Suspicion of a pharyngeal or laryngeal problem (for example, breathy voice quality), 4) Gurgly voice quality. |

There is risk of pneumonia and chest infection if the clinicians not aware of the red flags |

To make the clinician aware of the red flags for feeding and swallowing and Instrumental swallowing evaluation to avoid the risk of pneumonia

instrumentation allows the phoniatricians to gain more information about how the anatomical structures within the larynx are working. And to know the extent of swallow dysfunction, safety for food and the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies

|

|

Management of Eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties -Treatment selection will depend on the child’s age, cognitive and physical abilities, and specific swallowing and feeding problems -Treatment Options: 1-Postural and Positioning Techniques These techniques serve to protect the airway and offer safer transit of food and liquid. Techniques include chin down, chin up, head rotation, upright positioning (90° angle at hips and knees, feet on floor, with supports as needed), head stabilization (supported so as to present in chin-neutral position), cheek and jaw assist, reclining position, and side-lying positioning for infants.

2- Diet Modifications Typical modifications may include thickening thin liquids, softening, cutting/chopping, or pureeing solid foods to facilitate safety and ease of swallowing. Taste or temperature of a food may be altered to provide additional sensory input for swallowing. 3-Adaptive Equipment and Utensils These may be used with children who have feeding problems to foster independence with eating and increase swallow safety by controlling bolus size or achieving the optimal flow rate of liquids. Examples include modified nipples, cut out cups, angled forks and spoons, and sectioned plates. 4- Maneuvers Maneuvers are strategies used to change the timing or strength of movements of swallowing. Examples of maneuvers include Effortful swallow, Masako, or tongue hold, Mendelsohn maneuver, Supraglottic swallow, Super-supraglottic swallow. 5- Oral–Motor Treatments Oral–motor treatments include stimulation to—or actions of—the lips, jaw, tongue, soft palate, pharynx, larynx, and respiratory muscles. Oral–motor treatments range from passive (e.g., tapping, stroking, and vibration) to active (e.g., range-of-motion activities, resistance exercises, or chewing and swallowing exercises). Oral–motor treatments are intended to influence the physiologic underpinnings of the oropharyngeal mechanism in order to improve its functions. Some of these interventions can also incorporate sensory stimulation. 6- Feeding Strategies Feeding strategies include pacing and cue-based feeding. Pacing: Feeding strategies for children may include alternating bites of food with sips of liquid or swallowing 2–3 times per bite or sip. For infants, pacing can be accomplished by limiting the number of consecutive sucks. Strategies that slow the feeding rate may allow for more time between swallows to clear the bolus and may support more timely breaths.

Cue-based feeding: Most neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) have begun to move away from volume-driven feeding to cue-based feeding. In the NICU, the phoniatrician plays a critical role, supporting parents and other caregivers to understand and respond accordingly to the infant's communication during feeding. 7-Sensory Stimulation Techniques These may include thermal–tactile stimulation (e.g., using an iced lemon glycerin swab) or tactile stimulation (e.g., using a NUK brush) applied to the tongue or around the mouth. Sensory stimulation may be needed for children with reduced responses, overactive responses, or limited opportunities for sensory experiences. 8- Behavioral Interventions They are based on principles of behavioral modification and focus on increasing appropriate actions or behaviors and reducing maladaptive behaviors related to feeding. Examples include Feeding such as nasogastric tube, and gastrostomy. These approaches may be considered if the child’s swallowing safety and efficiency cannot reach a level of adequate function or does not adequately support nutrition and hydration. antecedent manipulation, shaping, prompting, modeling, stimulus fading, and differential reinforcement of alternate behavior, as well as implementation of basic mealtime principles (e.g., scheduled mealtimes in a neutral atmosphere with no food rewards). 9- Tube Non-nutritive sucking opportunities are thought to facilitate oral feeding skills in infants, most often via Pacifier. Children receiving nutrition and hydration via tube should be appropriate for brief ‘taste’ sessions over2–5 min multiple times per day. Spoon presentations with two to three drops of lemon juice or ice water may be tolerated without compromising pulmonary status and help to stimulate swallowing. Regular and thorough oral care is vital for all children. 10- Oral appliances or feeding devices 11-Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) |

Over time feeding, chewing and swallowing difficulties can lead to malnutrition and dehydration |

To maintaining respiratory health, optimising nutritional status

|

|

Managing saliva control - The reported prevalence of drooling ranges from 10% to 58%. In the assessment of affected patients, clinicians should determine its frequency, severity and impact on the quality of life of children and their caregivers. -A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of drooling is advisable. -Treatment Options: 1- Behavioral interventions: The aim of these interventions is to increase target behaviors, such as swallowing saliva, wiping lips and chin, improving head control, and teaching ways to manage drooling independently. Treatment techniques can include: instruction (e.g. please wipe your chin), prompting (e.g. giving a verbal prompt to swallow), positive reinforcement (e.g. praise), and/or self-management (instructions to swallow and wipe the chin) 2- Physical, oro-motor and oro-sensory therapies: These interventions involve correction of general body posture and head posture to eliminate the anterior loss of saliva from the oral cavity, therapy to improve lip and jaw closure as well as increasing tongue control, reducing tongue thrust , normalizing tone, and normalizing facial and oral sensation. 3- Pharmacologic treatments e.g. anticholinergic drugs 4-Botulinum toxin A injections to the salivary glands with ultrasound guidance if anticholinergic drugs provide insufficient benefit or are not tolerated. 5- Surgical interventions e.g. salivary gland excision, ligation, duct rerouting. 6- Intra-oral appliances e.g. the Exeter Lip Sensor, palatal training appliances. |

It affects the quality of life of those patients |

For clarification due to its importance |

|

Communication intervention The goal of communication therapy for children is to become active and independent Communicators in all of their daily environments.

A review of the evidence for language interventions showed that experimental studies exist to support intervention for vocabulary, grammar, narrative and social use of language. But, as with test materials, interventions may need to be adapted to meet the individual needs of children with restricted speech and movement and the impact of such adaptations on cognitive processing must be considered. To do this they need to develop as full a range of communication skills as possible and to have an Intelligible means of expressing all their needs and ideas.

The hearing problem should be assessed for the need of hearing aids and cochlear implant according to the profile of each CP case.

Children whose speech is often unintelligible may require augmentative and alternative systems of communication (AAC) to supplement their natural modes. The aim of AAC is to provide children all the vocabulary they need to communicate independently. AAC should be linked to verbal output from the conversational partner. |

Not to be missed |

For clarification |

|

Speech Manifestations Dysarthria in BDMH(CP) commonly affects all aspects of speech production: respiration, phonation, resonance, articulation and prosody. Impairments include: shallow, irregular breathing for speech; low pitched, harsh voice; reduced pitch variation/unexpected pitch breaks; hyper-nasality; and poor articulation. Although the underlying motor disorders vary (spasticity is associated with increased tone and reduced range of movement, choreo-athetosis is associated with involuntary movement and dysrhythmia), most characteristics (low pitch, poor breath control, imprecise articulation) affect the speech of children with both spastic and dyskinetic BDMH(CP) in addition to the cerebellar (with slowing down of articulatory movements, affected prosody with increased variability of pitch and loudness in addition to increased & equal stress) and mixed dysarthric types. The dyskinetic type is usually associated with severe degree of dysarthria up to anarthria due to the associated involuntary movements of the vocal tract. |

Not to be missed by clinicians |

To clarify speech manifestation to address these manifestations in rehabilitation programme |

|

Intervention for speech impairment Physiological approaches focusing on respiratory support and speech rate, which follow motor learning principles, show promise for children and young people with BDMH (CP).

PROMPT (Program for Restructuring Oral Musculature Phonetic Targets), a sensory-motor therapy in which therapists provide auditory, visual, tactile and kinesthetic cues for the production of speech sounds, help changes in lip and jaw control and gains improvement in intelligibility

Articulation therapy is not generally advised as a first line of treatment, due to the impaired control of multiple speech subsystems in BDMH dysarthria and the need for breath support to create clear vocal signal.

Oral motor therapy is widely used for improving chewing, swallowing and salivary control associated with dysarthria.

Careful application of articulation therapy techniques according to the dysarthric manifestations of the BDMH (CP) children. Syllable by syllable attack and multisyllabic segmentation are appropriate for spastic dysarthria rather than dyskinetic& cerebellar dysarthria that might get benefit from other techniques like soft articulatory contact and modeling respectively. |

Neglecting Oral motor therapy and speech therapy is affecting lip and jaw control and gains improvement in intelligibility

|

To clarify the steps of speech therapy in BDMH/CP patients improvement intelligibility of those patients |

|

Hearing impairment Discuss the following information: • Hearing impairment occurs in around 1 in 10 children and young people with BDMH (CP). • Prevalence of hearing impairment increases with increasing severity of motor impairment. • It is more common in people with dyskinetic or ataxic BDMH (CP) than in those with spastic BDMH (CP). • Regular ongoing hearing assessment is necessary & intervention with the use of hearing aids or cochlear implant should be discussed with the parents/ caregivers according to the profile of each patient. |

No risk |

To clarify that hearing impairment is common with dyskinetic BDMH(CP) |

|

Intellectual disability - Discuss the following: • Intellectual Disability (IQ below 70) occurs in around 1 in 2 children and young people with BDMH(CP). • Severe intellectual disability (IQ below 50) occurs in around 1 in 4 children and young people with BDMH(CP). • Intellectual disability increases with increasing severity of motor impairment. |

No risk |

Modification just for clarification |

|

Epilepsy -Epilepsy occurs in around 1 in 3 children with BDMH(CP) and 1 in 2 children with dyskinetic BDMH(CP). Dyskinetic movements should not be misinterpreted as epilepsy. -The seizures include focal, generalized & combined. -Diagnosis depends on family & personal history, characteristics of clinical events with electroencephalogram used as a gold standard. |

No risk |

To differentiate between epilepsy and dyskinetic movements |

|

Motoric problems The patient should be referred to the physiotherapist to assess the motoric condition Multiple techniques will be discussed with the parents including: -Bobath (neurodevelopmental approach) technique: it is multidisciplinary approach, involving physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech language therapists. -Roods approach (neuro- physiological approach) dealing with the activation and de-activation of sensory receptors, which is concerned with the interaction of somatic, autonomic and psychic factors and their role in regulation of motor behavior. |

No risk |

to clarify the physiotherapy techniques |