Ischemic Stroke

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Neurology Guidelines |

| Book: | Ischemic Stroke |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 10:19 PM |

Description

"last update: 9 May 2024"

- Acknowledgements

▶️ “We would like to acknowledge the Neurology Committee of National Egyptian Guidelines for adapting & reviewing these guidelines.

Chair of the panel: Hassan Hosni

Scientific group members: Azza Abdlnasser, Ahmed Elbassioni, Mona Ahmed Nada, Magdy Khalaf, Tarek Rageh, Mohamed Foad, Ahmed Fawzi Amin, Khaled Mohamed Ossama, Ahmed Ateia, Romany Adly.- Abbreviations

AF - Atrial fibrillation

ASC - Acute stroke centre

ASPECTS - Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score

BP - Blood pressure

CT - Computed tomography

CTA - Computed tomography angiography

DOAC - Direct oral anticoagulant

DWI - Diffusion-weighted imaging

FLAIR - Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

HDL - High density lipoprotein

ICH - Intracerebral haemorrhage

INR - International normalized ratio (for blood clotting time)

LDL - Low density lipoprotein

MCA - Middle cerebral artery

MR - Magnetic resonance

MRA - Magnetic resonance angiography

MRI - Magnetic resonance imaging

mRS - Modified Rankin Scale score

NHS - National Health Service

NICE - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

NIHSS - National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

PAF - Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

PFO - Patent foramen ovale

TIA - Transient ischaemic attack

TOE - Transoesophageal echocardiogram

VA - Vertebral artery

VKA - Vitamin K antagonist

WHO - World Health Organization- Glossary

Acute stroke service - Consists of: a) a comprehensive stroke centre (CSC) providing hyperacute, acute and inpatient rehabilitation including thrombectomy (thrombectomy centre) and neurosurgery; or b) an acute stroke centre (ASC) providing hyperacute, acute and inpatient rehabilitation. All components of a specialist acute stroke service should be based in a hospital that can investigate and manage people with acute stroke and their medical and neurological complications.

Alteplase - A medicine used for thrombolysis.

Angiography - A technique that uses X-ray technology to image blood vessels.

Anticoagulants - A group of medicines used to reduce the risk of clots by thinning the blood.

Antiplatelets - A group of medicines used to prevent the formation of clots by stopping platelets in the blood sticking together.

Antithrombotics - The generic name for all medicines that prevent the formation of blood clots. This includes antiplatelets and anticoagulants.

Atherosclerosis - Fatty deposits that harden on the inner wall of the arteries (atheroma) and roughen its surface; this makes the artery susceptible to blockage either by narrowing or by formation of a blood clot.

Atrial fibrillation - A heart condition that causes an irregular heartbeat, often faster than the normal heart rate.

Cardiovascular disease - Disease of the heart and/or blood vessels.

Carotid angioplasty - surgical procedure that widens the internal diameter of the carotid artery, after it has been narrowed by atherosclerosis.

Carotid arteries - Main blood vessels in the neck, which supply oxygenated blood to the brain.

Carotid stenosis - The narrowing of the carotid arteries in the neck.

Computed tomography (CT) - An X-ray technique used to examine the brain.

Cost-effectiveness - The extent to which the benefits of a treatment outweigh the costs.

Doppler ultrasound - An imaging technique that measures blood flow and velocity through blood vessels.

Gastrointestinal bleeding - Bleeding anywhere between the throat and the rectum.

Hyperlipidaemia - Raised levels of lipids (cholesterol, triglycerides or both) in the blood serum.

Hypertension - Raised blood pressure.

Ischemic stroke - A stroke that happens when a blood clot blocks an artery that is carrying blood to the brain.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - A non-invasive imaging technique that allows for detailed examination of the brain.

MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging - This type of scan shows areas of recent ischemic brain damage.

Stroke - A clinical syndrome, of presumed vascular origin, typified by rapidly developing signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral functions lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death.

Thrombectomy - The excision of a blood clot from a blood vessel.

Thrombolysis - The use of medicines to break up a blood clot. An example of a thrombolysis medicine is alteplase, also sometimes called tPA.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) - An acute loss of focal cerebral or ocular function with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours and which is thought to be due to inadequate cerebral or ocular blood supply as a result of low blood flow, thrombosis or embolism associated with diseases of the blood vessels, heart, or blood.- Executive Summary

These Guidelines are concerned with the diagnosis and

treatment decisions of Ischemic Stroke.

(A) Management of

TIA And Minor Stroke

1- Patients with acute focal neurological symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours of onset (i.e. suspected TIA) should be given aspirin 300 mg immediately, unless contraindicated by current medical condition of the patient, e.g. active bleeding varices, gastric ulcer or lower GIT bleeding, and assessed urgently within 24 hours by a stroke specialist clinician in a neurovascular clinic or an acute stroke unit. Strong recommendation

2- Patients with suspected TIA that occurred more than a week previously should be assessed by a stroke specialist clinician as soon as possible within 7 days. Strong recommendation

3- Patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke should be given antiplatelet therapy provided there is neither a contraindication nor a high risk of bleeding. The following regimens should be considered as soon as possible:

-

For patients within 24 hours of onset of TIA or minor ischemic stroke

and with a low risk of bleeding, the following dual antiplatelet therapy should

be given:

Clopidogrel (initial dose 300 mg followed by 75 mg per day) plus

aspirin (initial dose 300 mg followed by 75 mg per day for 21 days)

followed by monotherapy with clopidogrel 75 mg once daily

OR

- Ticagrelor (initial dose 180 mg followed by 90 mg twice daily) plus aspirin (300 mg followed by 75 mg daily for 30 days) followed by antiplatelet monotherapy with ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily or clopidogrel 75 mg once daily at the discretion of the prescriber;

- For patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke who are not appropriate for dual antiplatelet therapy, clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily should be given;

- A proton pump inhibitor should be considered for concurrent use with dual antiplatelet therapy to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage;

- For patients with recurrent TIA or stroke whilst taking clopidogrel, consideration should be given to clopidogrel resistance.

Strong recommendation

4- Patients with TIA or ischemic stroke should receive high-intensity statin therapy (e.g. atorvastatin 20-80 mg daily) started immediately. Strong recommendation

5- Patients with non-disabling ischemic stroke or TIA in atrial fibrillation should be anticoagulated, as soon as intracranial bleeding has been excluded, with an anticoagulant that has rapid onset, provided there are no other contraindications. Strong recommendation

6- Patients with ischemic stroke or TIA who after specialist assessment are considered candidates for carotid intervention should have carotid imaging performed within 24 hours of assessment. This includes carotid duplex ultrasound or either CT angiography or MR angiography. Strong recommendation

7- Patients with TIA or acute non-disabling ischemic stroke with stable neurological symptoms who have symptomatic severe carotid stenosis of 50–99% should be assessed and referred for carotid revascularization intervention to be performed as soon as possible within 7 days of the onset of symptoms. Strong recommendation

8- Patients with TIA or acute non-disabling ischemic stroke who have mild or moderate carotid stenosis of less than 50% should not undergo carotid intervention. Strong recommendation

(B) Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke

1- Patients with suspected acute stroke should be admitted directly to a hyperacute stroke service and be assessed for emergency stroke treatments by a specialist clinician without delay. Strong recommendation

2- Patients with suspected acute stroke should receive brain imaging as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital). Strong recommendation

3- Patients with stroke with a delayed presentation for whom reperfusion is potentially indicated may have CT or MR perfusion as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital). An alternative for patients who wake up with stroke is MRI measuring DWI-FLAIR mismatch. Conditional recommendation

4- Patients with acute ischemic stroke, regardless of age or stroke severity, in whom treatment can be started within 4.5 hours of known onset, should be considered for thrombolysis with alteplase. Strong recommendation

5- Patients with acute ischemic stroke, regardless of age or stroke severity, who were last known to be well more than 4.5 hours earlier, may be considered for thrombolysis with alteplase if:

- treatment can be started between 4.5 and 9 hours of known onset, or within 9 hours of the midpoint of sleep when they have woken with symptoms

AND

- they have evidence from CT/MR perfusion (core-perfusion mismatch) or MRI (DWI-FLAIR mismatch) of the potential to salvage brain tissue.

This should be irrespective of whether they have a large artery occlusion and require mechanical thrombectomy. Conditional recommendation

6- Thrombolysis should only be administered within a well-organised stroke service. Strong recommendation

7- Patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for mechanical thrombectomy should receive prior intravenous thrombolysis (unless contraindicated) irrespective of whether they have presented to an acute stroke centre or a thrombectomy centre. Every effort should be made to minimise process times throughout the treatment pathway and thrombolysis should not delay urgent transfer to a thrombectomy centre. Strong recommendation

8- Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke, who were previously independent (mRS 0-2), should be considered for combination intravenous thrombolysis and intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) and the procedure can begin within 6 hours of known onset. Strong recommendation

9- Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke and a contraindication to intravenous thrombolysis but not to thrombectomy, who were previously independent (mRS 0-2), should be considered for intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) and the procedure can begin within 6 hours of known onset. Strong recommendation

10- Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke and a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion (ICA and/or M1) causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) of onset between 6 and 24 hours ago, including wake-up stroke, and with no previous disability (mRS 0 or 1) may be considered for intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques, combined with thrombolysis if eligible) providing the following imaging criteria are met:

- Between 6 and 12 hours: an ASPECTS score of 3 or more, irrespective of the core infarct size;

- Between 12 and 24 hours: an ASPECTS score of 3 or more and CT or MRI perfusion mismatch of greater than 15 mL, irrespective of the core infarct size.

Conditional recommendation

11- Patients with acute ischemic stroke in the posterior circulation within 12 hours of onset may be considered for mechanical thrombectomy (combined with thrombolysis if eligible) if they have a confirmed intracranial vertebral or basilar artery occlusion and their NIHSS score is 10 or more, combined with a favourable PC-ASPECTS score and Pons-Midbrain Index. Caution should be exercised when considering mechanical thrombectomy for patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours of onset and/or over the age of 80 owing to the paucity of data in these groups. Conditional recommendation

12- Patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombolysis should be started on an antiplatelet agent after 24 hours unless contraindicated, once significant haemorrhage has been excluded. Strong recommendation

(C) LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT AND SECONDARY PREVENTION

1- Patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA should receive treatment for secondary prevention as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. Strong recommendation

2- People with stroke or TIA should receive a comprehensive and personalised strategy for vascular prevention including medication and lifestyle factors, which should be implemented as soon as possible and should continue long-term. Strong recommendation

3- People with stroke or TIA should have their risk factors and secondary prevention reviewed and monitored at least once a year in primary care. Strong recommendation

4- People with stroke or TIA for whom secondary prevention is appropriate should be investigated for risk factors as soon as possible within 1 week of onset. Strong recommendation

5- Provided they are eligible for any resultant intervention, people with stroke or TIA should be investigated for the following risk factors:

a. ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis;

b. atrial fibrillation;

c. structural cardiac disease.

Strong recommendation

6- People with non-disabling carotid artery territory stroke or TIA should be considered for carotid revascularisation, and if they agree with intervention:

a. they should have carotid imaging (duplex ultrasound, MR or CT angiography) performed urgently to assess the degree of stenosis;

b. if the initial test identifies a relevant severe stenosis (greater than or equal to 50%), a second or repeat non-invasive imaging investigation should be performed to confirm the degree of stenosis. This confirmatory test should be carried out urgently to avoid delaying any intervention.

Strong recommendation

7- People with non-disabling carotid artery territory stroke or TIA should be considered for carotid revascularisation if the symptomatic internal carotid artery has a stenosis of greater than or equal to 50%. Strong recommendation

8- Patients with atrial fibrillation and symptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis should be managed for both conditions unless there are contraindications. Strong recommendation

9- People with stroke or TIA should have their blood pressure checked, and treatment should be initiated or increased as tolerated to consistently achieve a clinic systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg, equivalent to a home systolic blood pressure below 125 mmHg. The exception is for people with severe bilateral carotid artery stenosis, for whom a systolic blood pressure target of 140–150 mmHg is appropriate. Concern about potential adverse effects should not impede the initiation of treatment that prevents stroke, major cardiovascular events or mortality. Strong recommendation

10- For people with stroke or TIA aged 55 or over, antihypertensive treatment should be initiated with a long-acting dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker or a thiazide-like diuretic. If target blood pressure is not achieved, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker should be added. Strong recommendation

11- For people with stroke or TIA younger than 55 years, antihypertensive treatment should be initiated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Strong recommendation

12- People with stroke or TIA should have their blood pressure-lowering treatment monitored frequently in primary care and increased to achieve target blood pressure as quickly and safely as tolerated. People whose blood pressure remains above target despite treatment should be checked for medication adherence at each visit before escalation of treatment, and people who do not achieve their target blood pressure despite escalated treatment should be referred for a specialist opinion. Once blood pressure is controlled to target, people taking antihypertensive treatment should be reviewed at least annually. Strong recommendation

13- People with ischemic stroke or TIA should be offered personalised advice and support on lifestyle factors to reduce cardiovascular risk, including diet, physical activity, weight reduction, alcohol moderation and smoking cessation. Strong recommendation

14- People with ischemic stroke or TIA should be offered treatment with a statin unless contraindicated or investigation of their stroke or TIA confirms no evidence of atherosclerosis. Treatment should:

a. begin with a high-intensity statin such as atorvastatin 80 mg daily. A lower dose should be used if there is the potential for medication interactions or a high risk of adverse effects;

b. be with an alternative statin at the maximum tolerated dose if a high-intensity statin is unsuitable or not tolerated.

Strong recommendation

15- Lipid-lowering treatment for people with ischemic stroke or TIA and evidence of atherosclerosis should aim to reduce fasting LDL-cholesterol to below 1.8 mmol/L (equivalent to a non-HDL-cholesterol of below 2.5 mmol/L in a non-fasting sample). If this is not achieved at first review at 4-6 weeks, the prescriber should:

a. discuss adherence and tolerability;

b. optimise dietary and lifestyle measures through personalised advice and support;

c. consider increasing to a higher dose of statin if this was not prescribed from the outset;

d. consider adding ezetimibe 10 mg daily;

e. consider the use of additional agents such as injectables (inclisiran or monoclonal antibodies to PCSK9) or bempedoic acid (for statin-intolerant people taking ezetimibe monotherapy);

f. continue to escalate lipid-lowering therapy (in combination if necessary) at regular intervals in order to reduce LDL-cholesterol to below 1.8 mmol/L.

Strong recommendation

16- In people with ischemic stroke or TIA below 60 years of age with very high cholesterol (below 30 years with total cholesterol above 7.5 mmol/L or 30 years or older with total cholesterol concentration above 9.0 mmol/L) consider a diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Strong recommendation

17- For long-term prevention of vascular events in people with ischemic stroke or TIA without paroxysmal or permanent atrial fibrillation:

a. clopidogrel 75 mg daily should be the standard antithrombotic treatment;

b. aspirin 75 mg daily should be used for those who are unable to tolerate clopidogrel;

c. if a patient has a recurrent cardiovascular event on clopidogrel, clopidogrel resistance may be considered.

d. The combination of aspirin and clopidogrel is not recommended for long-term prevention of vascular events unless there is another indication e.g. acute coronary syndrome, recent coronary stent.

Strong recommendation

18- People with ischemic stroke with acute haemorrhagic transformation may be treated with long-term antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy unless the prescriber considers that the risks outweigh the benefits. Conditional recommendation

19- Patients who have a spontaneous (non-traumatic) intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) whilst taking an antithrombotic (antiplatelet or anticoagulant) medication for the prevention of occlusive vascular events should be considered for restarting antiplatelet treatment beyond 24 hours after ICH symptom onset provided stabilization of general condition and blood pressure. Strong recommendation

20- For people with ischemic stroke or TIA and paroxysmal, persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation (AF: valvular or non-valvular) or atrial flutter, oral anticoagulation should be the standard long-term treatment for stroke prevention. Anticoagulant treatment:

a. should not be given if brain imaging has identified significant haemorrhage;

b. should not be commenced in people with severe hypertension (clinic blood pressure of 180/120 or higher), which should be treated first;

c. may be considered for patients with moderate-to-severe stroke from 5-14 days after onset. Wherever possible these patients should be offered participation in a trial of the timing of initiation of anticoagulation after stroke. Aspirin 300 mg daily should be used in the meantime;

d. should be considered for patients with mild stroke earlier than 5 days if the prescriber considers the benefits to outweigh the risk of early intracranial haemorrhage. Aspirin 300 mg daily should be used in the meantime;

e. should be initiated within 14 days of onset of stroke in all those considered appropriate for secondary prevention;

f. should be initiated immediately after a TIA once brain imaging has excluded haemorrhage, using an agent with a rapid onset (e.g. DOAC in non-valvular AF or subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin while initiating a VKA for those with valvular AF);

g. should include measures to reduce bleeding risk, using a validated tool to identify modifiable risk factors.

Strong recommendation

21- First-line treatment for people with ischemic stroke or TIA due to non valvular AF should be anticoagulation with a DOAC. Strong recommendation

22- People with ischemic stroke or TIA due to valvular/rheumatic AF or with mechanical heart valve replacement, and those with contraindications or intolerance to DOAC treatment, should receive anticoagulation with adjusted-dose warfarin (target INR 2.5, range 2.0 to 3.0) with a target time in the therapeutic range of greater than 72%. Strong recommendation

23- For people with cardioembolic TIA or stroke for whom treatment with anticoagulation is considered inappropriate because of a high risk of bleeding:

a. antiplatelet treatment should not be used as an alternative when there are absolute contraindications to anticoagulation (e.g. undiagnosed bleeding);

b. measures should be taken to reduce bleeding risk, using a validated tool to identify modifiable risk factors. If after intervention for relevant risk factors the bleeding risk is considered too high for anticoagulation, antiplatelet treatment should not be routinely used as an alternative;

c. a left atrial appendage occlusion device may be considered as an alternative, provided the short-term peri-procedural use of antiplatelet therapy is an acceptable risk.

Strong recommendation

24- People with cardioembolic TIA or stroke for whom treatment with anticoagulation is considered inappropriate for reasons other than the risk of bleeding may be considered for antiplatelet treatment to reduce the risk of recurrent vaso-occlusive disease. Conditional recommendation

25- Patients with ischemic stroke or TIA not already diagnosed with atrial fibrillation or flutter should undergo an initial period of cardiac monitoring for a minimum of 24 hours if they are appropriate for anticoagulation. Strong recommendation

26- People with ischemic stroke or TIA and a PFO should receive optimal secondary prevention treatment, including antiplatelet therapy, treatment for high blood pressure, lipid-lowering therapy and lifestyle modification. Anticoagulation is not recommended unless there is another recognised indication. Strong recommendation

27- Selected people below the age of 60 with ischemic stroke or TIA of otherwise undetermined aetiology, in association with a PFO and a right-to-left shunt or an atrial septal aneurysm, may be considered for endovascular PFO device closure within six months of the index event to prevent recurrent stroke. This decision should be made after careful consideration of the benefits and risks by a multidisciplinary team including the patient’s physician and the cardiologist performing the procedure. The balance of risk and benefit from the procedure, including the risk of atrial fibrillation and other recognised peri-procedural complications should be fully considered and explained to the person with stroke. Strong recommendation

28- People older than 60 years with ischemic stroke or TIA of otherwise undetermined aetiology and a PFO may be offered closure in the context of a clinical trial or prospective registry. Conditional recommendation

29- People with stroke or TIA should be investigated with transthoracic echocardiography if the detection of a structural cardiac abnormality would prompt a change of management and if they have:

a. clinical or ECG findings suggestive of structural cardiac disease that would require assessment in its own right, or

b. unexplained stroke or TIA, especially if other brain imaging features suggestive of cardioembolism are present.

Strong recommendation

30- People with ischemic stroke or TIA due to severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis should be offered dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for the first three months in addition to optimal secondary prevention including blood pressure treatment, lipid-lowering therapy and lifestyle modification. Endovascular or surgical intervention should only be offered in the context of a clinical trial. Strong recommendation

- Introduction, purpose, scope and audience

INTRODUCTION

Weighted crude incidence rates (CIRs) of stroke in Egypt is 202/100,000. Based on recent statistics; stroke is the 3rd leading cause of mortality in Egypt.

Despite significant improvement of stroke care in Egypt over the last 5 years, there is a delay in pre-hospital and in-hospital management of acute stroke patients.

Nearly 30% of patients are potential candidates for endovascular therapy, while only 20% of eligible patients received rTPA (standard of care).

SCOPE AND PURPOSE

This guideline covers the management of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) in adults (i.e., people aged over 16 years).

This edition includes updated evidence with literature searches completed up to September 2022 and with some major publications since that date also included.

This guideline is not intended to overrule regulations or standards concerning the provision of services and should be considered in conjunction with them. In considering and implementing this guideline, users are advised to also consult and follow all appropriate legislation, standards and good practice.

TARGET AUDIENCE

The guideline is intended for:

· those providing care – neurology, intensive care, emergency medicine and internal medicine doctors, nursing staff dealing with stroke patients.

· those commissioning, providing or sanctioning stroke services;

- Methods

We adopted WHO proposed seven distinct steps for development of clinical guidelines to ensure a thorough and rigorous process.

The final research questions and consensus questions are structured using the ‘Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome’ (PICO) format. Each question is assigned to an appropriate topic group according to the scope.

A literature search is undertaken for each individual question to identify studies that help to answer the question and provide evidence that is robust enough to allow recommendations to be made. Literature searching is coordinated by the stroke guideline team. These initial searches look for guidelines, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses only and cover the following databases:

a. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

b. MEDLINE.

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation. inclusion/exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

· Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

· Selecting only national and/or international guidelines Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later)

· Selecting peer reviewed publications only

· Selecting guidelines written in English language

· Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input.

· Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

· Developing organisation/authors

· Date of publication, posting, and release

· Country/language of publication

· Date of posting and/or release

· Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. The panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 50% on the rigour dimension was retained). The Guideline Development Group has decided to adapt the current guidelines guided by most recent NICE (2019, reviewed 2022) and AHA/ASA (2019 & 2021) recommendations on ischemic stroke management.

EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT

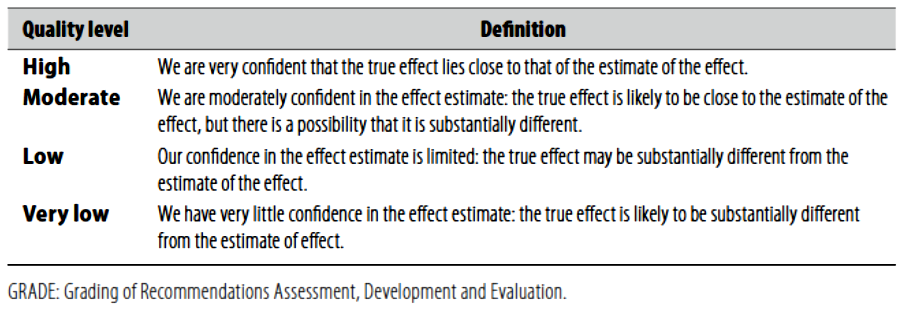

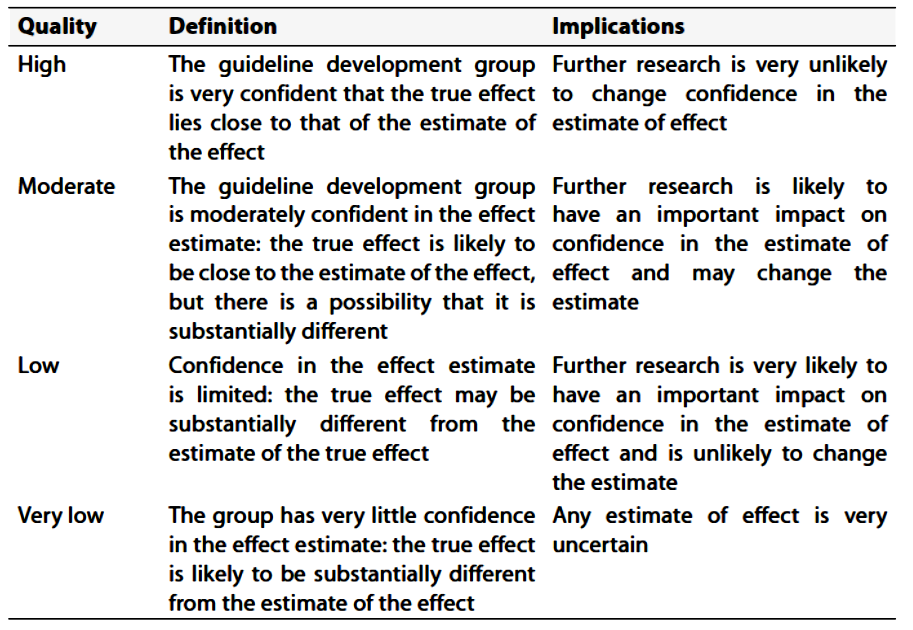

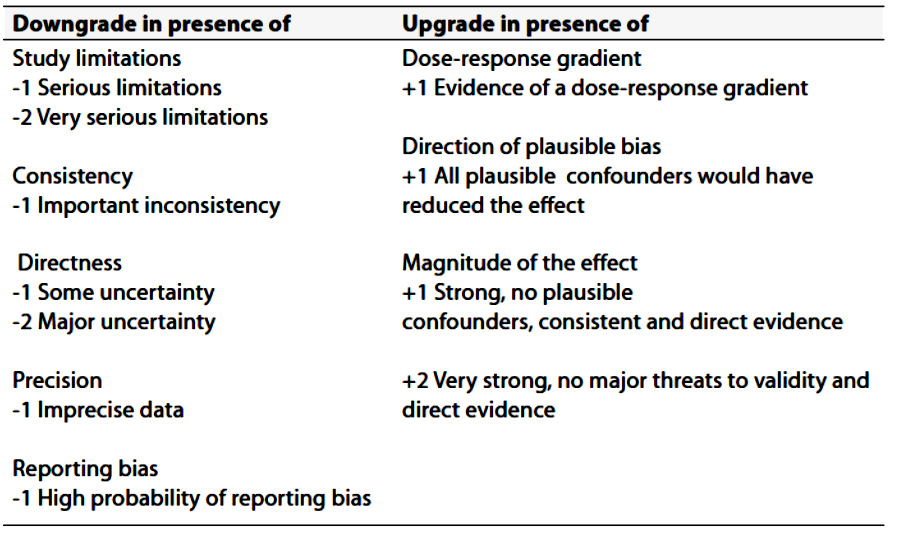

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available through the GRC secretariat and on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

THE STRENGTH OF THE RECOMMENDATION

The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

§ Strong Recommandations

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

§ Conditional recommendations

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

§ When not to make recommendations

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

(Table-1) Quality of evidence in GRADE (Table-2) Significance of the four levels

of evidence

- Recommendations

(I) ACUTE CARE OF ISCHEMIC STROKE & TIA

(A) Management of TIA And Minor Stroke

Recommendations

1- Patients with acute focal neurological symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours of onset (i.e. suspected TIA) should be given aspirin 300 mg immediately, unless contraindicated by current medical condition of the patient, e.g. active bleeding varices, gastric ulcer or lower GIT bleeding, and assessed urgently within 24 hours by a stroke specialist clinician in a neurovascular clinic or an acute stroke unit. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Lavallee et al, 2007; Rothwell et al, 2016)

2- Patients with suspected TIA that occurred more than a week previously should be assessed by a stroke specialist clinician as soon as possible within 7 days. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Giles and Rothwell, 2007)

3- Patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke should be given antiplatelet therapy provided there is neither a contraindication nor a high risk of bleeding. The following regimens should be considered as soon as possible:

-

For patients within 24 hours of onset of TIA or minor ischemic stroke

and with a low risk of bleeding, the following dual antiplatelet therapy should

be given:

Clopidogrel (initial dose 300 mg followed by 75 mg per day) plus

aspirin (initial dose 300 mg followed by 75 mg per day for 21 days)

followed by monotherapy with clopidogrel 75 mg once daily

OR

- Ticagrelor (initial dose 180 mg followed by 90 mg twice daily) plus aspirin (300 mg followed by 75 mg daily for 30 days) followed by antiplatelet monotherapy with ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily or clopidogrel 75 mg once daily at the discretion of the prescriber;

- For patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke who are not appropriate for dual antiplatelet therapy, clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily should be given;

- A proton pump inhibitor should be considered for concurrent use with dual antiplatelet therapy to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage;

- For patients with recurrent TIA or stroke whilst taking clopidogrel, consideration should be given to clopidogrel resistance.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Wang et al, 2013, 2021c; Johnston et al, 2018, 2020)

4- Patients with TIA or ischemic stroke should receive high-intensity statin therapy (e.g. atorvastatin 20-80 mg daily) started immediately. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Rothwell et al, 2007; NICE, 2010b, 2022e, 2023a)

5- Patients with non-disabling ischemic stroke or TIA in atrial fibrillation should be anticoagulated, as soon as intracranial bleeding has been excluded, with an anticoagulant that has rapid onset, provided there are no other contraindications. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

6- Patients with ischemic stroke or TIA who after specialist assessment are considered candidates for carotid intervention should have carotid imaging performed within 24 hours of assessment. This includes carotid duplex ultrasound or either CT angiography or MR angiography. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence

7- Patients with TIA or acute non-disabling ischemic stroke with stable neurological symptoms who have symptomatic severe carotid stenosis of 50–99% should be assessed and referred for carotid revascularization intervention to be performed as soon as possible within 7 days of the onset of symptoms. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Barnett et al, 1998; Rothwell et al, 2003b; NICE, 2022d, 2023a)

8- Patients with TIA or acute non-disabling ischemic stroke who have mild or moderate carotid stenosis of less than 50% should not undergo carotid intervention. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Barnett et al, 1998; Rothwell et al, 2003b; NICE, 2022d, 2023a)

(B) Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke

Recommendations

1- Patients with suspected acute stroke should be admitted directly to a hyperacute stroke service and be assessed for emergency stroke treatments by a specialist clinician without delay. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration, 2013)

2- Patients with suspected acute stroke should receive brain imaging as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital). Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Wardlaw et al, 2004)

3- Patients with stroke with a delayed presentation for whom reperfusion is potentially indicated may have CT or MR perfusion as soon as possible (at most within 1 hour of arrival at hospital). An alternative for patients who wake up with stroke is MRI measuring DWI-FLAIR mismatch. Conditional recommendation & Moderate level of evidence

4- Patients with acute ischemic stroke, regardless of age or stroke severity, in whom treatment can be started within 4.5 hours of known onset, should be considered for thrombolysis with alteplase.

5- Patients with acute ischemic stroke, regardless of age or stroke severity, who were last known to be well more than 4.5 hours earlier, may be considered for thrombolysis with alteplase if:

- treatment can be started between 4.5 and 9 hours of known onset, or within 9 hours of the midpoint of sleep when they have woken with symptoms

AND

- they have evidence from CT/MR perfusion (core-perfusion mismatch) or MRI (DWI-FLAIR mismatch) of the potential to salvage brain tissue.

This should be irrespective of whether they have a large artery occlusion and require mechanical thrombectomy.

Conditional recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Thomalla et al, 2018; Campbell et al, 2019)

6 - Thrombolysis should only be administered within a well-organised stroke service. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Wardlaw et al, 2012)

7 - Patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for mechanical thrombectomy should receive prior intravenous thrombolysis (unless contraindicated) irrespective of whether they have presented to an acute stroke centre or a thrombectomy centre. Every effort should be made to minimise process times throughout the treatment pathway and thrombolysis should not delay urgent transfer to a thrombectomy centre. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Yang et al, 2020; LeCouffe et al, 2021; Suzuki et al, 2021; Zi et al, 2021; Fischer et al, 2022; Mitchell et al, 2022; Turc et al, 2022)

8 - Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke, who were previously independent (mRS 0-2), should be considered for combination intravenous thrombolysis and intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) and the procedure can begin within 6 hours of known onset. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Goyal et al, 2016)

9 - Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke and a contraindication to intravenous thrombolysis but not to thrombectomy, who were previously independent (mRS 0-2), should be considered for intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) and the procedure can begin within 6 hours of known onset. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Goyal et al, 2016)

10- Patients with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke and a proximal intracranial large artery occlusion (ICA and/or M1) causing a disabling neurological deficit (NIHSS score of 6 or more) of onset between 6 and 24 hours ago, including wake-up stroke, and with no previous disability (mRS 0 or 1) may be considered for intra-arterial clot extraction (using a stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques, combined with thrombolysis if eligible) providing the following imaging criteria are met:

- Between 6 and 12 hours: an ASPECTS score of 3 or more, irrespective of the core infarct size;

- Between 12 and 24 hours: an ASPECTS score of 3 or more and CT or MRI perfusion mismatch of greater than 15 mL, irrespective of the core infarct size.

Conditional recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Sarraj et al, 2023; Huo et al, 2023)

11- Patients with acute ischemic stroke in the posterior circulation within 12 hours of onset may be considered for mechanical thrombectomy (combined with thrombolysis if eligible) if they have a confirmed intracranial vertebral or basilar artery occlusion and their NIHSS score is 10 or more, combined with a favourable PC-ASPECTS score and Pons-Midbrain Index. Caution should be exercised when considering mechanical thrombectomy for patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours of onset and/or over the age of 80 owing to the paucity of data in these groups. Conditional recommendation & Low level of evidence (Liu et al, 2020; Langezaal et al, 2021, Tao et al, 2022; Jovin et al, 2022a)

12- Patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombolysis should be started on an antiplatelet agent after 24 hours unless contraindicated, once significant haemorrhage has been excluded. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Sandercock et al, 2015)

(C) LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT AND SECONDARY PREVENTION

Recommendations

1- Patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA should receive treatment for secondary prevention as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Progress Collaborative Group, 2001; Rothwell et al, 2007; NICE, 200b, 2022e, 2023a)

2- People with stroke or TIA should receive a comprehensive and personalised strategy for vascular prevention including medication and lifestyle factors, which should be implemented as soon as possible and should continue long-term. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

3- People with stroke or TIA should have their risk factors and secondary prevention reviewed and monitored at least once a year in primary care. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence4 - People with stroke or TIA for whom secondary prevention is appropriate should be investigated for risk factors as soon as possible within 1 week of onset. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

5 - Provided they are eligible for any resultant intervention, people with stroke or TIA should be investigated for the following risk factors:

a. ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis;

b. atrial fibrillation;

c. structural cardiac disease.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

6 - People with non-disabling carotid artery territory stroke or TIA should be considered for carotid revascularisation, and if they agree with intervention:

a. they should have carotid imaging (duplex ultrasound, MR or CT angiography) performed urgently to assess the degree of stenosis;

b. if the initial test identifies a relevant severe stenosis (greater than or equal to 50%), a second or repeat non-invasive imaging investigation should be performed to confirm the degree of stenosis. This confirmatory test should be carried out urgently to avoid delaying any intervention.

Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Wardlaw et al, 2004)

7- People with non-disabling carotid artery territory stroke or TIA should be considered for carotid revascularisation if the symptomatic internal carotid artery has a stenosis of greater than or equal to 50%. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Rothwell et al, 2004, 2005; Rerkasem and Rothwell, 2011)

8 - Patients with atrial fibrillation and symptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis should be managed for both conditions unless there are contraindications. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

9- People with stroke or TIA should have their blood pressure checked, and treatment should be initiated or increased as tolerated to consistently achieve a clinic systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg, equivalent to a home systolic blood pressure below 125 mmHg. The exception is for people with severe bilateral carotid artery stenosis, for whom a systolic blood pressure target of 140–150 mmHg is appropriate. Concern about potential adverse effects should not impede the initiation of treatment that prevents stroke, major cardiovascular events or mortality. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Rothwell et al, 2003; Ettehad et al, 2016).10 - For people with stroke or TIA aged 55 or over, antihypertensive treatment should be initiated with a long-acting dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker or a thiazide-like diuretic. If target blood pressure is not achieved, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker should be added. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (PROGRESS Collaborative Group, 2001; NICE, 2022a)

11- For people with stroke or TIA younger than 55 years, antihypertensive treatment should be initiated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (NICE, 2022a)

12- People with stroke or TIA should have their blood pressure-lowering treatment monitored frequently in primary care and increased to achieve target blood pressure as quickly and safely as tolerated. People whose blood pressure remains above target despite treatment should be checked for medication adherence at each visit before escalation of treatment, and people who do not achieve their target blood pressure despite escalated treatment should be referred for a specialist opinion. Once blood pressure is controlled to target, people taking antihypertensive treatment should be reviewed at least annually. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Rothwell et al, 2007; NICE, 2022a)

13- People with ischemic stroke or TIA should be offered personalised advice and support on lifestyle factors to reduce cardiovascular risk, including diet, physical activity, weight reduction, alcohol moderation and smoking cessation. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (NICE, 2016a, b; 2021b, d; 2023a; Amarenco et al, 2020; NHS England Accelerated Access Collaborative, 2021; Lee et al, 2022)

14- People with ischemic stroke or TIA should be offered treatment with a statin unless contraindicated or investigation of their stroke or TIA confirms no evidence of atherosclerosis. Treatment should:

a. begin with a high-intensity statin such as atorvastatin 80 mg daily. A lower dose should be used if there is the potential for medication interactions or a high risk of adverse effects;

b. be with an alternative statin at the maximum tolerated dose if a high-intensity statin is unsuitable or not tolerated. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (NICE, 2016a, b; 2021b, d; 2023a; Amarenco et al, 2020; NHS England Accelerated Access Collaborative, 2021; Lee et al, 2022)

15- Lipid-lowering treatment for people with ischemic stroke or TIA and evidence of atherosclerosis should aim to reduce fasting LDL-cholesterol to below 1.8 mmol/L (equivalent to a non-HDL-cholesterol of below 2.5 mmol/L in a non-fasting sample). If this is not achieved at first review at 4-6 weeks, the prescriber should:

a. discuss adherence and tolerability;

b. optimise dietary and lifestyle measures through personalised advice and support;

c. consider increasing to a higher dose of statin if this was not prescribed from the outset;

d. consider adding ezetimibe 10 mg daily;

e. consider the use of additional agents such as injectables (inclisiran or monoclonal antibodies to PCSK9) or bempedoic acid (for statin-intolerant people taking ezetimibe monotherapy);

f. continue to escalate lipid-lowering therapy (in combination if necessary) at regular intervals in order to reduce LDL-cholesterol to below 1.8 mmol/L.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (NICE, 2016a, b; 2021b, d; 2023a; Amarenco et al, 2020; NHS England Accelerated Access Collaborative, 2021; Lee et al, 2022)

16 - In people with ischemic stroke or TIA below 60 years of age with very high cholesterol (below 30 years with total cholesterol above 7.5 mmol/L or 30 years or older with total cholesterol concentration above 9.0 mmol/L) consider a diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (NICE, 2023b)

17- For long-term prevention of vascular events in people with ischemic stroke or TIA without paroxysmal or permanent atrial fibrillation:

a. clopidogrel 75 mg daily should be the standard antithrombotic treatment;

b. aspirin 75 mg daily should be used for those who are unable to tolerate clopidogrel;

c. if a patient has a recurrent cardiovascular event on clopidogrel, clopidogrel resistance may be considered.

d. The combination of aspirin and clopidogrel is not recommended for long-term prevention of vascular events unless there is another indication e.g. acute coronary syndrome, recent coronary stent.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (NICE, 2010a)

18- People with ischemic stroke with acute haemorrhagic transformation may be treated with long-term antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy unless the prescriber considers that the risks outweigh the benefits. Conditional recommendation & Moderate level of evidence

19- Patients who have a spontaneous (non-traumatic) intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) whilst taking an antithrombotic (antiplatelet or anticoagulant) medication for the prevention of occlusive vascular events should be considered for restarting antiplatelet treatment beyond 24 hours after ICH symptom onset provided stabilization of general condition and blood pressure. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Al-Shahi Salman et al, 2019, 2021)

20- For people with ischemic stroke or TIA and paroxysmal, persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation (AF: valvular or non-valvular) or atrial flutter, oral anticoagulation should be the standard long-term treatment for stroke prevention. Anticoagulant treatment:

a. should not be given if brain imaging has identified significant haemorrhage;

b. should not be commenced in people with severe hypertension (clinic blood pressure of 180/120 or higher), which should be treated first;

c. may be considered for patients with moderate-to-severe stroke from 5-14 days after onset. Wherever possible these patients should be offered participation in a trial of the timing of initiation of anticoagulation after stroke. Aspirin 300 mg daily should be used in the meantime;

d. should be considered for patients with mild stroke earlier than 5 days if the prescriber considers the benefits to outweigh the risk of early intracranial haemorrhage. Aspirin 300 mg daily should be used in the meantime;

e. should be initiated within 14 days of onset of stroke in all those considered appropriate for secondary prevention;

f. should be initiated immediately after a TIA once brain imaging has excluded haemorrhage, using an agent with a rapid onset (e.g. DOAC in non-valvular AF or subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin while initiating a VKA for those with valvular AF);

g. should include measures to reduce bleeding risk, using a validated tool to identify modifiable risk factors.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (EAFT Study Group, 1993; Paciaroni et al, 2015; Gioia et al, 2016; Klijn et al, 2019; Hindricks et al, 2021; Labovitz et al, 2021; Steffel et al, 2021; De Marchis et al, 2022)

21- First-line treatment for people with ischemic stroke or TIA due to non valvular AF should be anticoagulation with a DOAC. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence

22- People with ischemic stroke or TIA due to valvular/rheumatic AF or with mechanical heart valve replacement, and those with contraindications or intolerance to DOAC treatment, should receive anticoagulation with adjusted-dose warfarin (target INR 2.5, range 2.0 to 3.0) with a target time in the therapeutic range of greater than 72%. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (EAFT Study Group, 1993; Eikelboom et al, 2013; Ruff et al, 2014; Graham et al, 2015; Makam et al, 2018; Hirschl and Kundi, 2019; Hindricks et al, 2021; Shen et al, 2020; Steffel et al, 2021; Xu et al, 2021; Connolly et al, 2022)

23 - For people with cardioembolic TIA or stroke for whom treatment with anticoagulation is considered inappropriate because of a high risk of bleeding:

a. antiplatelet treatment should not be used as an alternative when there are absolute contraindications to anticoagulation (e.g. undiagnosed bleeding);

b. measures should be taken to reduce bleeding risk, using a validated tool to identify modifiable risk factors. If after intervention for relevant risk factors the bleeding risk is considered too high for anticoagulation, antiplatelet treatment should not be routinely used as an alternative;

c. a left atrial appendage occlusion device may be considered as an alternative, provided the short-term peri-procedural use of antiplatelet therapy is an acceptable risk.

Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Reddy et al, 2013; NICE, 2021a)

24- People with cardioembolic TIA or stroke for whom treatment with anticoagulation is considered inappropriate for reasons other than the risk of bleeding may be considered for antiplatelet treatment to reduce the risk of recurrent vaso-occlusive disease. Conditional recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Benz et al, 2022)

25- Patients with ischemic stroke or TIA not already diagnosed with atrial fibrillation or flutter should undergo an initial period of cardiac monitoring for a minimum of 24 hours if they are appropriate for anticoagulation. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Kishore et al, 2014)

26- People with ischemic stroke or TIA and a PFO should receive optimal secondary prevention treatment, including antiplatelet therapy, treatment for high blood pressure, lipid-lowering therapy and lifestyle modification. Anticoagulation is not recommended unless there is another recognised indication. Strong recommendation & Moderate level of evidence (Homma et al, 2002)

27- Selected people below the age of 60 with ischemic stroke or TIA of otherwise undetermined aetiology, in association with a PFO and a right-to-left shunt or an atrial septal aneurysm, may be considered for endovascular PFO device closure within six months of the index event to prevent recurrent stroke. This decision should be made after careful consideration of the benefits and risks by a multidisciplinary team including the patient’s physician and the cardiologist performing the procedure. The balance of risk and benefit from the procedure, including the risk of atrial fibrillation and other recognised peri-procedural complications should be fully considered and explained to the person with stroke. Strong recommendation & Low level of evidence (Furlan et al, 2012; Meier at al, 2013; Søndergaard et al, 2017; Saver et al, 2017; Mas et al, 2017; Lee at al, 2018)

28 - People older than 60 years with ischemic stroke or TIA of otherwise undetermined aetiology and a PFO may be offered closure in the context of a clinical trial or prospective registry. Conditional recommendation & Low level of evidence (Furlan et al, 2012; Meier at al, 2013; Søndergaard et al, 2017; Saver et al, 2017; Mas et al, 2017; Lee at al, 2018)

29 - People with stroke or TIA should be investigated with transthoracic echocardiography if the detection of a structural cardiac abnormality would prompt a change of management and if they have:

a. clinical or ECG findings suggestive of structural cardiac disease that would require assessment in its own right, or

b. unexplained stroke or TIA, especially if other brain imaging features suggestive of cardioembolism are present.

Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Holmes et al, 2014)

30 - People with ischemic stroke or TIA due to severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis should be offered dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for the first three months in addition to optimal secondary prevention including blood pressure treatment, lipid-lowering therapy and lifestyle modification. Endovascular or surgical intervention should only be offered in the context of a clinical trial. Strong recommendation & High level of evidence (Chimowitz et al 2005, 2011)

- Updating the guideline

To keep these

recommendations valid, all guidelines need to be periodically updated. This will

be done whenever strong evidence is available and necessitates recommendation

updates.

- Implementation considerations

In this section key recommendations are provided to guide the funding, planning and delivery of services along the entire pathway of stroke care. These recommendations will not provide the anticipated benefits for people with stroke unless organisations that plan and deliver health and social care fully support their implementation.

Recommendations:

1. Comprehensive stroke services should include the whole stroke pathway from prevention (including neurovascular services) through pre-hospital and acute care, early rehabilitation, secondary prevention, early supported discharge, community rehabilitation, systematic follow-up, palliative care and long-term support.

2. A public education and professional training strategy should be developed and implemented to ensure that the public and emergency personnel (e.g. staff in emergency call centres) can recognise when a person has a suspected stroke or TIA and respond appropriately. This should be implemented in such a way that it can be formally evaluated.

3. Along the pathway of stroke care, there should be protocols between healthcare providers and social services that enable seamless and safe transfers of care without delay.

4. The provision of comprehensive acute stroke services may require the development of hub-and-spoke models of care (where a few hospitals in a region are designated to provide the hyperacute care for all patients), or telemedicine networks and other forms of cross-site working.

5.The optimal disposition of acute stroke services will depend on the geography of the area served, with the objective of delivering the maximum number of time-critical treatments to the greatest number of people with stroke.

6. A public education and professional training strategy should be developed and implemented to ensure that the public and emergency personnel (e.g. staff in emergency call centres) can recognise when a person has a suspected stroke or TIA and respond appropriately. This should be implemented in such a way that it can be formally evaluated.

7. Healthcare providers should enact all the secondary stroke prevention measures recommended in this guideline. Effective secondary prevention should be assured through a process of regular audit and monitoring.

8. Healthcare authorities should play an active role in promoting secondary vascular prevention, which is a public health issue as well as being relevant to the individual person with stroke.

9. Stroke rehabilitation services should be provided to reduce limitation in activities, increase participation and improve the quality of life of people with stroke using therapeutic and adaptive strategies.

- Clinical indicators for monitoring

(I) ACUTE CARE OF ISCHEMIC STROKE & TIA

1. Emergency CT brain imaging for patients with suspected acute stroke, including the 24/7 provision of CT brain / MRI brain imaging for follow up.

2. Treatment with thrombolysis for eligible patients with acute ischaemic stroke or emergency transfere for stroke ready hospital as soon as possible.

3. Direct admission of patients with acute stroke to a hyperacute stroke unit providing active management of physiological status and homeostasis within 4 hours of arrival at hospital.

(II) LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT AND SECONDARY PREVENTION

1. Identify and treat patient modifiable vascular risk factors e.g. DM, IHD, HTN, AF, CAS according to patient discharge summary.

2. Provide all patient with stroke or TIA with detailed plan for treatments and follow up tailored to their risk profile.- Research needs

1- Cost effective studies for implementation of acute stroke intervention Vs Thrombolysis Vs best medical treatment in certain situations in Egyptian population.

2- Cost effective studies for genetic screening for ischemic stroke risk stratification for 1ry prevention of stroke.

3- Needs assessment studies for maximizing numbers of stroke ready centres providing comprehensive stroke services.- Annexes

Table 1 Eligibility criteria for extending thrombolysis to 4.5-9 hours and wake-up stroke

Time window Imaging Imaging criteria Wake-up stroke >4.5 hours from last seen well, no upper limit MRI

DWI-FLAIR mismatch DWI lesion and no FLAIR lesion Wake-up stroke or unknown onset time >4.5 hours from last seen well, and within 9 hours

of the midpoint of sleep. The midpoint of sleep is the time halfway between

going to bed and waking up CT

or MRI core-perfusion mismatch Suggested: mismatch ratio greater than 1.2,

a mismatch volume greater than 10 mL, and an ischemic core volume <70 mL Known onset time 4.5-9 hours CT

or MRI core-perfusion mismatch Suggested: mismatch ratio greater than 1.2,

a mismatch volume greater than 10 mL, and an ischemic core volume <70 mL

- References

1. Barnett, H. J., Taylor, D. W., Eliasziw, M., Fox, A. J., Ferguson, G. G., Haynes, R. B., et al. (1998). Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators New England Journal of Medicine, 339(20), 1415-1425.

2. Campbell, B. C. V., Ma, H., Ringleb, P. A., Parsons, M. W., Churilov, L., Bendszus, M., et al. (2019). Extending thrombolysis to 4·5-9 h and wake-up stroke using perfusion imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data Lancet, 394(10193), 139-147.

3. Emberson, J., Lees, K. R., Lyden, P., Blackwell, L., Albers, G., Bluhmki, E., et al. (2014). Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials Lancet, 384(9958), 1929-1935.

4. Giles, M. F., & Rothwell, P. M. (2007). Risk of stroke early after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet Neurol, 6(12), 1063-1072.

5. Johnston, S. C., Amarenco, P., Denison, H., Evans, S. R., Himmelmann, A., James, S., et al. (2020). Ticagrelor and Aspirin or Aspirin Alone in Acute Ischemic Stroke or TIA New England Journal of Medicine, 383(3), 207-217.

6. Johnston, S. C., Easton, J. D., Farrant, M., Barsan, W., Conwit, R. A., Elm, J. J., et al. (2018). Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA New England Journal of Medicine, 379(3), 215-225.

7. Lavallee, P. C., Meseguer, E., Abboud, H., Cabrejo, L., Olivot, J. M., Simon, O., et al. (2007). A transient ischemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects Lancet Neurology, 6(11), 953-960.

8. Menon, B. K., Buck, B. H., Singh, N., Deschaintre, Y., Almekhlafi, M. A., Coutts, S. B., et al. (2022). Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischemic stroke in Canada (AcT): a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial The Lancet, 400(10347), 161-169.

9. NICE. (2010b). Clinical guideline [CG91] Depression in Adults with a Chronic Physical Health Problem: Treatment and Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91

10. NICE. (2022b). NICE Guideline [NG136] Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

11. NICE. (2022d). NICE guideline [NG222] Depression in adults: treatment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222

12. NICE. (2022e). NICE guideline [NG128] Stroke and transient ischemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128

13. NICE. (2023a). NICE guideline [NG209] Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209

14. Progress Collaborative Group. (2001). Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischemic attack Lancet, 358(9287), 1033-1041.

15. Rothwell, P. M. (2007). Making the most of secondary prevention Stroke, 38(6), 1726.

16. Rothwell, P. M., Algra, A., Chen, Z., Diener, H. C., Norrving, B., & Mehta, Z. (2016). Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials Lancet, 388(10042), 365-375.

17. Rothwell, P. M., Gutnikov, S. A., Warlow, C. P., & European Carotid Surgery Trialist's, C. (2003b). Reanalysis of the final results of the European Carotid Surgery Trial Stroke, 34(2), 514-523.

18. Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration. (2013). Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD000197.

19. Thomalla, G., Cheng, B., Gellissen, S., Golsari, A., Gerloff, C., Fiehler, J., et al. (2018). MRI-Guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset New England Journal of Medicine, 379(7), 611-622.

20. Wang, Y., Meng, X., Wang, A., Xie, X., Pan, Y., Johnston, S. C., et al. (2021c). Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in CYP2C19 Loss-of-Function Carriers with Stroke or TIA New England Journal of Medicine.

21. Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Liu, L., Wang, D., Wang, C., et al. (2013). Clopidogrel with Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack New England Journal of Medicine, 369(1), 11-19.

22. Wardlaw, J. M., Murray, V., Berge, E., del Zoppo, G., Sandercock, P., Lindley, R. L., et al. (2012). Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet, 379(9834), 2364-2372.

23. Wardlaw, J. M., Seymour, J., Cairns, J., Keir, S., Lewis, S., & Sandercock, P. (2004). Immediate computed tomography scanning of acute stroke is cost-effective and improves quality of life Stroke, 35(11), 2477-2483.

24. Yang, P., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Li, Z., Zhou, Y., Xu, Y., et al. (2020). Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke New England Journal of Medicine, 382(21), 1981-1993.

25. LeCouffe, N. E., Kappelhof, M., Treurniet, K. M., Rinkel, L. A., Bruggeman, A. E., Berkhemer, O. A., et al. (2021). A Randomized Trial of Intravenous Alteplase before Endovascular Treatment for Stroke N Engl J Med, 385(20), 1833-1844.

26. Suzuki, K., Aoki, J., Nishiyama, Y., Kimura, K., Matsumaru, Y., Hayakawa, M., et al. (2021). Effect of Mechanical Thrombectomy without vs with Intravenous Thrombolysis on Functional Outcome among Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: The SKIP Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 325(3), 244-253.

27. Zi, W., Qiu, Z., Li, F., Sang, H., Wu, D., Luo, W., et al. (2021). Effect of Endovascular Treatment Alone vs Intravenous Alteplase Plus Endovascular Treatment on Functional Independence in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: The DEVT Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA, 325(3), 234-243.

28. Fischer, U., Kaesmacher, J., Strbian, D., Eker, O., Cognard, C., Plattner, P. S., et al. (2022). Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous alteplase plus thrombectomy in patients with stroke: an open-label, blinded-outcome, randomised non-inferiority trial Lancet, 400(10346), 104-115.

29. Mitchell, P. J., Yan, B., Churilov, L., Dowling, R. J., Bush, S., Nguyen, T., et al. (2022). DIRECT-SAFE: A Randomized Controlled Trial of DIRECT Endovascular Clot Retrieval versus Standard Bridging Therapy J Stroke, 24(1), 57-64.

30. Turc, G., Tsivgoulis, G., Audebert, H. J., Boogaarts, H., Bhogal, P., De Marchis, G. M., et al. (2022b). European Stroke Organisation (ESO)-European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) expedited recommendation on indication for intravenous thrombolysis before mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and anterior circulation large vessel occlusion J Neurointerv Surg, 14(3), 209.

31. Goyal, M., Menon, B. K., van Zwam, W. H., Dippel, D. W., Mitchell, P. J., Demchuk, A. M., et al. (2016). Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials Lancet, 387, 1723-1731.

32. Sarraj, A., Hassan, A. E., Abraham, M. G., Ortega-Gutierrez, S., Kasner, S. E., Hussain, M. S., et al. (2023). Trial of Endovascular Thrombectomy for Large Ischemic Strokes New England Journal of Medicine.

33. Huo, X., Ma, G., Tong, X., Zhang, X., Pan, Y., Nguyen, T. N., et al. (2023). Trial of Endovascular Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke with Large Infarct New England Journal of Medicine, Epub ahead of print.

34. Liu, X., Dai, Q., Ye, R., Zi, W., Liu, Y., Wang, H., et al. (2020). Endovascular treatment versus standard medical treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (BEST): an open-label, randomised controlled trial Lancet Neurol, 19(2), 115-122.

35. Langezaal, L. C. M., Van Der Hoeven, E. J. R. J., Mont'Alverne, F. J. A., De Carvalho, J. J. F., Lima, F. O., Dippel, D. W. J., et al. (2021). Endovascular therapy for stroke due to basilar-artery occlusion New England Journal of Medicine, 384(20), 1910-1920.

36. Tao, C., Nogueira, R. G., Zhu, Y., Sun, J., Han, H., Yuan, G., et al. (2022). Trial of Endovascular Treatment of Acute Basilar-Artery Occlusion New England Journal of Medicine, 387(15), 1361-1372.

37. Jovin, T. G., Li, C., Wu, L., Wu, C., Chen, J., Jiang, C., et al. (2022a). Trial of Thrombectomy 6 to 24 Hours after Stroke Due to Basilar-Artery Occlusion New England Journal of Medicine, 387(15), 1373-1384.

38. Sandercock, A. G., Counsell, C., & Kane Edward, J. (2015). Anticoagulants for acute ischemic stroke Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(3), CD000024.

39. Rothwell, P. M., Eliasziw, M., Gutnikov, S. A., Warlow, C. P., Barnett, H. J., & Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists, C. (2004). Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery Lancet, 363(9413), 915-924.

40. Rothwell, P. M., Mehta, Z., Howard, S. C., Gutnikov, S. A., & Warlow, C. P. (2005). Treating individuals 3: from subgroups to individuals: general principles and the example of carotid endarterectomy Lancet, 365(9455), 256-265.

41. Rerkasem, K., & Rothwell, P. M. (2011). Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis Cochrane Database Syst Rev(4), CD001081.

42. Rothwell, P. M., Eliasziw, M., Gutnikov, S. A., Fox, A. J., Taylor, D. W., Mayberg, M. R., et al. (2003a). Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis Lancet, 361(9352), 107-116.

43. Ettehad, D., Emdin, C. A., Kiran, A., Anderson, S. G., Callender, T., Emberson, J., et al. (2016). Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lancet, 387(10022), 957-967.

44. NICE. (2022a). NICE guideline [NG220] Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng220

45. Rothwell, P. M. (2007). Making the most of secondary prevention Stroke, 38(6), 1726.

46. NICE. (2016a). Interventional procedures guidance [IPG548] Mechanical clot retrieval for treating acute ischemic stroke. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg548

47. NICE. (2016b). Quality Standard 2: Stroke in adults. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS2

48. NICE. (2021b). Technology appraisal guidance [TA733] Inclisiran for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA733

49. NICE. (2021d). Technology appraisal guidance [TA694] Bempedoic acid with ezetimibe for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA694

50. NICE. (2023a). NICE guideline [NG209] Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209

51. Amarenco, P., Kim, J. S., Labreuche, J., Charles, H., Abtan, J., Béjot, Y., et al. (2020). A Comparison of Two LDL Cholesterol Targets after Ischemic Stroke New England Journal of Medicine, 382(1), 9-19.

52. NHS England. (2022). National Service Model for an Integrated Community Stroke Service. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/stroke-integrated-community-service-february-2022.pdf

53. Lee, M., Cheng, C. Y., Wu, Y. L., Lee, J. D., Hsu, C. Y., & Ovbiagele, B. (2022). Association Between Intensity of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Reduction With Statin-Based Therapies and Secondary Stroke Prevention: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials JAMA Neurol, 79(4), 349-358.

54. NICE. (2023b). Clinical guideline [CG103] Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG103

55. NICE. (2010a). Technology appraisal guidance [TA210] Clopidogrel and modified-release dipyridamole for the prevention of occlusive vascular events. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA210

56. Al-Shahi Salman, R., Minks, D. P., Mitra, D., Rodrigues, M. A., Bhatnagar, P., du Plessis, J. C., et al. (2019). Effects of antiplatelet therapy on stroke risk by brain imaging features of intracerebral haemorrhage and cerebral small vessel diseases: subgroup analyses of the RESTART randomised, open-label trial The Lancet Neurology, 18(7), 643-652.

57. Al-Shahi Salman, R., Dennis, M. S., Sandercock, P. A. G., Sudlow, C. L. M., Wardlaw, J. M., Whiteley, W. N., et al. (2021). Effects of Antiplatelet Therapy After Stroke Caused by Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Extended Follow-up of the RESTART Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Neurology, 78(10), 1179-1186.

58. EAFT Study Group. (1993). Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group Lancet, 342(8882), 1255-1262.

59. Paciaroni, M., Agnelli, G., Falocci, N., Caso, V., Becattini, C., Marcheselli, S., et al. (2015). Early Recurrence and Cerebral Bleeding in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation: Effect of Anticoagulation and Its Timing: The RAF Study Stroke, 46(8), 2175-2182.

60. Gioia, L. C., Kate, M., Sivakumar, L., Hussain, D., Kalashyan, H., Buck, B., et al. (2016). Early Rivaroxaban Use After Cardioembolic Stroke May Not Result in Hemorrhagic Transformation: A Prospective Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study Stroke, 47(7), 1917-1919.

61. Klijn, C. J., Paciaroni, M., Berge, E., Korompoki, E., Kõrv, J., Lal, A., et al. (2019). Antithrombotic treatment for secondary prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic events in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack and non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A European Stroke Organisation guideline Eur Stroke J, 4(3), 198-223.

62. Hindricks, G., Potpara, T., Dagres, N., Arbelo, E., Bax, J. J., Blomström-Lundqvist, C., et al. (2021). 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC European Heart Journal, 42(5), 373-498.

63. Labovitz, A. J., Rose, D. Z., Fradley, M. G., Meriwether, J. N., Renati, S., Martin, R., et al. (2021). Early Apixaban Use Following Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the AREST Trial Stroke, 52(4), 1164-1171.

64. Steffel, J., Collins, R., Antz, M., Cornu, P., Desteghe, L., Haeusler, K. G., et al. (2021). 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Europace, 23(10), 1612-1676.

65. De Marchis, G. M., Seiffge, D. J., Schaedelin, S., Wilson, D., Caso, V., Acciarresi, M., et al. (2022). Early versus late start of direct oral anticoagulants after acute ischemic stroke linked to atrial fibrillation: an observational study and individual patient data pooled analysis Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 93(2), 119.

66. Eikelboom, J. W., Connolly, S. J., Brueckmann, M., Granger, C. B., Kappetein, A. P., Mack, M. J., et al. (2013). Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves New England Journal of Medicine, 369(13), 1206-1214.

67. Ruff, C. T., Giugliano, R. P., Braunwald, E., Hoffman, E. B., Deenadayalu, N., Ezekowitz, M. D., et al. (2014). Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials Lancet, 383(9921), 955-962.

68. Graham, D. J., Reichman, M. E., Wernecke, M., Zhang, R., Southworth, M. R., Levenson, M., et al. (2015). Cardiovascular, bleeding, and mortality risks in elderly Medicare patients treated with dabigatran or warfarin for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation Circulation, 131(2), 157-164.

69. Makam, R. C. P., Hoaglin, D. C., McManus, D. D., Wang, V., Gore, J. M., Spencer, F. A., et al. (2018). Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants approved for cardiovascular indications: Systematic review and meta-analysis PLoS One, 13(5), e0197583.

70. Hirschl, M., & Kundi, M. (2019). Safety and efficacy of direct acting oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation - a network meta-analysis of real-world data Vasa, 48(2), 134-147.

71. Shen, N. N., Wu, Y., Wang, N., Kong, L. C., Zhang, C., Wang, J. L., et al. (2020). Direct Oral Anticoagulants vs. Vitamin-K Antagonists in the Elderly With Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review Comparing Benefits and Harms Between Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials Front Cardiovasc Med, 7, 132.

72. Steffel, J., Collins, R., Antz, M., Cornu, P., Desteghe, L., Haeusler, K. G., et al. (2021). 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Europace, 23(10), 1612-1676.