Hoarseness (Dysphonia)

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Otorhinolaryngology, Audiovestibular & Phoniatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | Hoarseness (Dysphonia) |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 8:51 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 April 2024"

- Committee

Chair of the Panel:

Usama Abdel Naseer

Scientific Group Members:

Abdalla Anayet, Abdelrahman Eltahaan, Ahmed Mostafa, Alaa Gaafar, Amr Taha, Ashraf Lotfy, Athar Reda Ibrahim, Bahaa Eltoukhy, Haytham Elfarargy, Hazem Dewidar, Ihab Sifin, Loay Elsharkawy, Mai Mohammed Salama, Mina Esmat, Rania Abdou, Reda Sharkawy, Saad Elzayat, Samir Halim.

Abbreviations:

QOL = Quality of life

Glossary:

Hoarseness (dysphonia) is defined as a disorder characterized by altered vocal quality, pitch, loudness, or vocal effort that impairs communication or reduces voice-related QOL.

Impaired communication is defined as a decreased or limited ability to interact vocally with others.

Reduced voice-related QOL is defined as a self-perceived decrement in physical, emotional, social, or economic status as a result of voice-related dysfunction.

- Introduction

Nearly one-third of the population has impaired voice production at some point in their lives.1,2 Hoarseness is more prevalent in certain groups, such as teachers and older adults, but all age groups and both genders can be affected.1-6 In addition to the impact on health and quality of life (QOL),7,8 hoarseness leads to frequent health care visits and several billion dollars in lost productivity annually from work absenteeism.9 Hoarseness is often caused by benign or self-limited conditions, but may also be the presenting symptom of a more serious or progressive condition requiring prompt diagnosis and management

➡️Purpose

The primary purpose of this guideline is to improve the quality of care for patients with hoarseness based on current best evidence. Expert consensus to fill evidence gaps, when used, is explicitly stated, and is supported with a detailed evidence profile for transparency. Specific objectives of the guideline are to reduce inappropriate variations in care, produce optimal health outcomes, and minimize harm.

This guideline addresses the identification, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hoarseness (dysphonia). In addition, it highlights needs and management options in special populations or in patients who have modifying factors. Furthermore, this guideline is intended to enhance the accurate diagnosis of hoarseness (dysphonia), promote appropriate intervention in patients with hoarseness, highlight the need for evaluation and intervention in special populations, promote appropriate therapeutic options with outcomes assessment, and improve counseling and education for prevention and management of hoarseness. This guideline may also be suitable for deriving a performance measure on hoarseness.

➡️The Target Audience

The guideline is intended for all

clinicians who are likely to diagnose and manage patients at any age with

hoarseness (dysphonia), and it applies to any setting in which hoarseness

(dysphonia) would be identified, monitored, or managed.

- Executive summary

This guideline provides evidence-based recommendations on managing hoarseness (dysphonia) which affects nearly one-third of the population at some point in their lives. This guideline applies to all age groups evaluated in a setting where hoarseness would be identified or managed. It is intended for all clinicians who are likely to diagnose and manage patients with hoarseness.

· The clinician should not routinely prescribe antibiotics to treat hoarseness.

· The clinician should advocate voice therapy for patients diagnosed with hoarseness that reduces voice-related QOL.

· The clinician should diagnose hoarseness (dysphonia) in a patient with altered voice quality, pitch, loudness, or vocal effort that impairs communication or reduces voice-related QOL.

· The clinician should assess the patient with hoarseness by history and/or physical examination for factors that modify management, such as one or more of the following: recent surgical procedures involving the neck or affecting the recurrent laryngeal nerve, recent endotracheal intubation, radiation treatment to the neck, a history of tobacco abuse, and occupation as a singer or vocal performer.

· The clinician should visualize the patient’s larynx or refer the patient to a clinician who can visualize the larynx, when hoarseness fails to resolve by a maximum of three months after onset, or irrespective of duration if a serious underlying cause is suspected.

· The clinician should not obtain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the patient with a primary complaint of hoarseness prior to visualizing the larynx.

· The clinician should not prescribe anti reflux medications for patients with hoarseness without signs or symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

· The clinician should not routinely prescribe oral corticosteroids to treat hoarseness.

· The clinician should visualize the larynx before prescribing voice therapy and document/communicate the results to the speech-language pathologist.

· The clinician should prescribe or refer the patient to a clinician who can prescribe, botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of hoarseness caused by adductor spasmodic dysphonia.

· The clinician may perform laryngoscopy at any time in a patient with hoarseness or may refer the patient to a clinician who can visualize the larynx.

· The clinician may educate/counsel patients with hoarseness about control/preventive measures.

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

▶️ Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence).

▶️ Selecting only national and/or international guidelines.

▶️ Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later).

▶️ Selecting peer reviewed publications only.

▶️ Selecting guidelines written in English language.

▶️ Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input.

▶️ Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations.

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

▶️ Developing organization/authors

▶️ Date of publication, posting, and release

▶️ Country/language of publication

▶️ Date of posting and/or release

▶️ Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers.

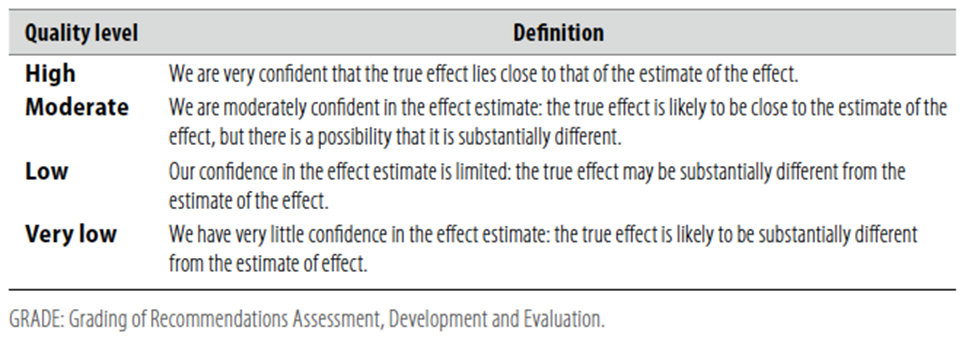

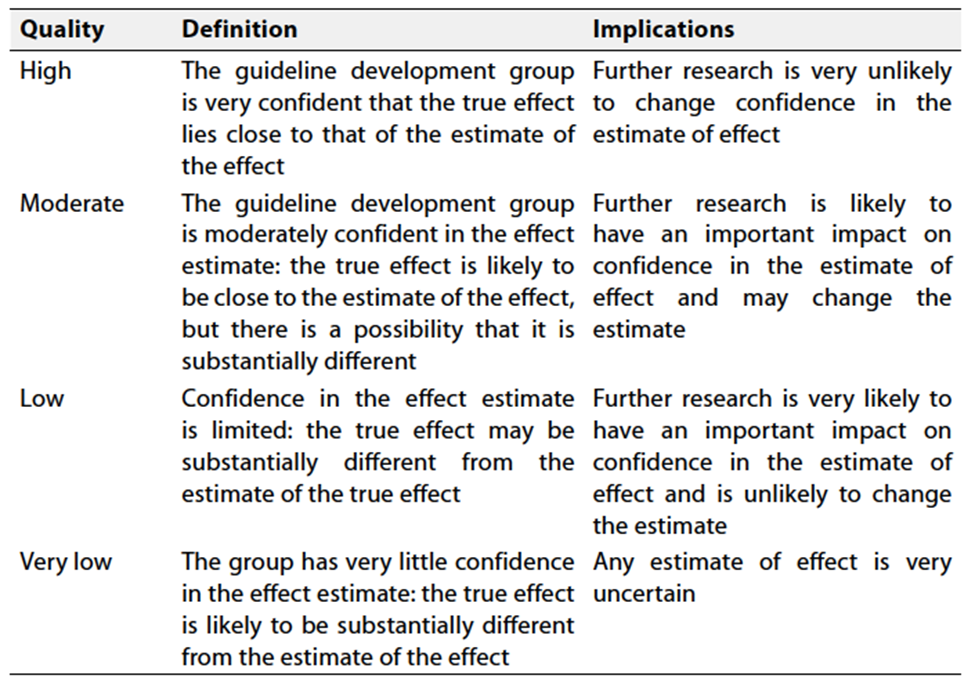

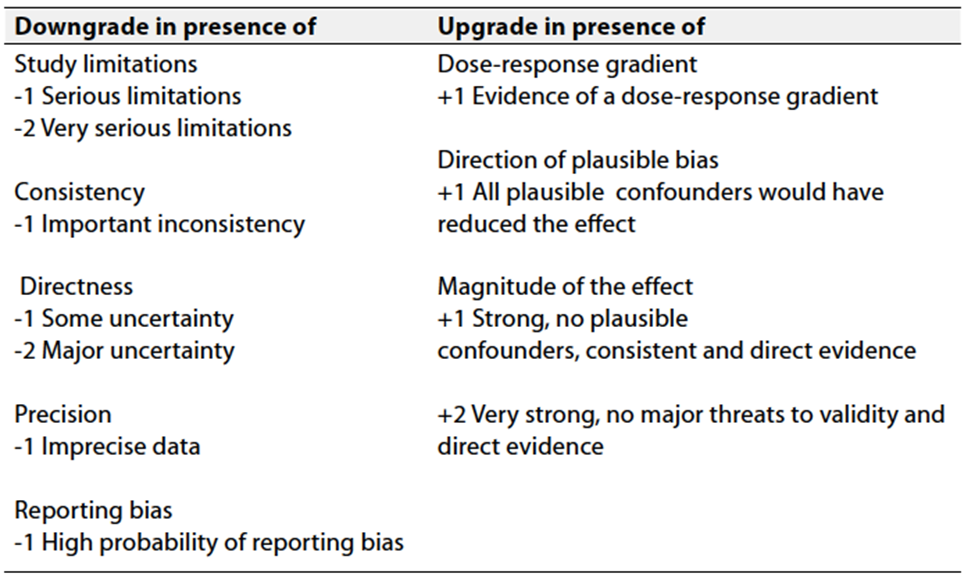

Evidence assessment

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available on the following sites:

▶️ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org.

▶️ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/.

▶️ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

Table 1 Quality of evidence in GRADE

Table 2 Significance of the four levels of evidence

Table 3 Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of evidence

- Recommendations

1. DIAGNOSIS: Clinicians should diagnose hoarseness (dysphonia) in a patient with altered voice quality, pitch, loudness, or vocal effort that impairs communication or reduces voice-related QOL.

2. MODIFYING FACTORS:

Clinicians should assess the patient with hoarseness by history

and/or physical examination for factors that modify management such as one or

more of the following: recent surgical procedures involving the neck or

affecting the recurrent laryngeal nerve, recent endotracheal intubation,

radiation treatment to the neck, a history of tobacco abuse, and occupation as

a singer or vocal performer.

➡️Strong Recommendation

High quality evidence based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.6-12

3A. LARYNGOSCOPY AND HOARSENESS: Clinicians may perform laryngoscopy or may refer the patient to a clinician who can visualize the larynx, at any time in a patient with hoarseness.

➡️Conditional

Moderate quality evidence based on observational studies, expert opinion, and a balance of benefit and harm.13,14

3B. INDICATIONS FOR LARYNGOSCOPY: Clinicians should visualize the patient’s larynx or refer the patient to a clinician who can visualize the larynx, when hoarseness fails to resolve by a maximum of three months after onset, or irrespective of duration if a serious underlying cause is suspected.

➡️Strong Recommendation

High quality evidence based on observational studies, expert opinion, and a preponderance of benefit over harm.15-19

4. IMAGING: Clinicians should not obtain computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient with a primary complaint of hoarseness prior to visualizing the larynx.

➡️Strong Recommendation against imaging

High quality evidence based on observational studies of harm, absence of evidence concerning benefit, and a preponderance of harm over benefit.20-25

5A. ANTI-REFLUX MEDICATION AND HOARSENESS. Clinicians should not prescribe anti-reflux medications for patients with hoarseness without signs or symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

➡️Strong Recommendation against prescribing

Moderate quality evidence based on randomized trials with limitations and observational studies with a preponderance of harm over benefit.26,27

5B. ANTI-REFLUX MEDICATION AND CHRONIC LARYNGITIS. Clinicians may prescribe anti-reflux medication for patients with hoarseness and signs of chronic laryngitis.

➡️Conditional

Low quality evidence based on observational studies with limitations and a relative balance of benefit and harm.28-31

6. CORTICOSTEROID THERAPY: Clinicians should not routinely prescribe oral corticosteroids to treat hoarseness.

➡️Strong Recommendation against prescribing

High Quality evidence based on randomized trials showing adverse events and absence of clinical trials demonstrating benefits with a preponderance of harm over benefit for steroid use.32,33

7. ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY: Clinicians should not routinely prescribe antibiotics to treat hoarseness.

➡️Strong recommendation against prescribing

High quality index based on systematic reviews and randomized trials showing ineffectiveness of antibiotic therapy and a preponderance of harm over benefit.34-36

8A. LARYNGOSCOPY PRIOR TO VOICE THERAPY: Clinicians should visualize the larynx before prescribing voice therapy and document/communicate the results to the speech-language pathologist.

➡️Strong Recommendation

High quality index based on observational studies showing benefit

and a preponderance of benefit

over harm.37-39

8B. ADVOCATING FOR VOICE THERAPY: Clinicians should advocate voice therapy for patients diagnosed with hoarseness (dysphonia) that reduces voice-related QOL.

➡️Strong recommendation

High quality index based on systematic reviews and randomized trials with a preponderance of benefit over harm.40-43

9. SURGERY: Clinicians should advocate for surgery as a therapeutic option in patients with hoarseness with suspected: 1) laryngeal malignancy, 2) benign laryngeal soft tissue lesions, or 3) glottic insufficiency.

➡️Strong Recommendation

High quality index based on observational studies demonstrating

a benefit of surgery in these conditions and a

preponderance of benefit over harm.44-47

10. BOTULINUM TOXIN: Clinicians should prescribe or refer the patient to a clinician who can prescribe botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of hoarseness caused by spasmodic dysphonia.

➡️Strong Recommendation

High quality index based on randomized controlled trials with minor limitations and preponderance of benefit over harm.48-52

11. PREVENTION: Clinicians may educate/counsel patients with hoarseness about control/preventive measures.

➡️Conditional

Moderate quality evidence based on observational studies and small randomized trials of poor quality.53-57

Clinical Indicators of monitoring:

▶️ Clinicians should diagnose hoarseness putting in consideration modifying factors such as medical, surgical and pharmacotherapy history.

▶️ Clinicians should perform or send patient for laryngoscopy if hoarseness persists for more than 3 months or irrespective of duration if a serious underlying cause is suspected.

▶️ Clinician should not prescribe anti-reflux treatment for patients with hoarseness except if there are symptoms and signs of reflux.

▶️ Clinicians should not prescribe antimicrobial therapy and corticosteroids as a routine therapy for patients with hoarseness.

▶️ Clinicians should advocate voice therapy for patients diagnosed with hoarseness (dysphonia) that reduces voice-related QOL.

▶️ Surgery should be advocated as a therapeutic option in patients with hoarseness with suspected: 1) laryngeal malignancy, 2) benign laryngeal soft tissue lesions, or 3) glottic insufficiency.

▶️ Clinicians should prescribe or refer the patient to a clinician who can prescribe botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of hoarseness caused by spasmodic dysphonia.

Research Needs.

▶️ Hoarseness is known to be common, but the prevalence of hoarseness in certain populations such as children is not well known. Additionally, the prevalence of specific etiologies of hoarseness is not known. Descriptive statistics would help to shape thinking on distribution of resources, levels of care, and cost mandates.

▶️ Some of the entities that might benefit from study include viral laryngitis, fungal laryngitis, inhaler-related laryngitis, voice abuse, reflux, and benign lesions (i.e., nodules, polyps, cysts, etc.). A better understanding of the natural history of these disorders could be obtained through prospective observational studies and will have clear implications for the necessity and timing of behavioral, medical, and surgical interventions.

▶️ Prospective studies on the value of steroids and antibiotics for infectious laryngitis are also lacking. Given the known potential harms from these medications, prospective studies examining the benefits relative to placebo are warranted.

▶️ Well conducted and controlled studies of anti-reflux therapy for patients with hoarseness and for patients with signs of laryngeal inflammation would help to establish the value of these medications. Further clarification of which hoarse patients may benefit from reflux treatment would help to optimize outcomes and minimize costs and potential side effects. Future studies may benefit from strict inclusion criteria and specific investigation of the outcome of hoarseness (dysphonia) control.

▶️ Although ancillary testing such as radiographic imaging is often performed to assist in diagnosing the underlying cause of hoarseness, the role of these tests has not been clearly defined. Their usefulness as screening tools is unclear and the cost effectiveness of their use has not been established.

▶️ Study of the effect of early screening and diagnosis is warranted. Voice therapy has been shown to provide short-term benefit for hoarse patients, but long-term efficacy has not been shown. Also, the relative harm of voice therapy has not been studied (e.g., lost work time, anxiety), making the

▶️ risk/benefit ratio difficult to evaluate.

▶️ As office-based procedures are developed to manage causes of hoarseness previously treated in the operating room, comparative studies on the safety and efficacy of office-based procedures relative to those performed under general anesthesia are needed (e.g. injection vs open thyroplasty).

- References

1. Seth R. Schwartz, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Hoarseness (Dysphonia) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;141:S1-S31.

2. Robert J. Stachler, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Hoarseness (Dysphonia) (Update) Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 2018;158:S1–S42.

3. Brouha XD, Tromp DM, de Leeuw JR, et al. Laryngeal cancer patients: analysis of patient delay at different tumor stages. Head Neck 2005;27:289–95.

4. Scott S, Robinson K, Wilson JA, et al. Patient-reported problems associated with dysphonia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1997;22:37– 40.

5. Zur KB, Cotton S, Kelchner L, et al. Pediatric Voice Handicap Index (pVHI): a new tool for evaluating pediatric dysphonia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:77–82.

6. Yeung P, Erskine C, Mathews P, et al. Voice changes and thyroid surgery: is pre-operative indirect laryngoscopy necessary? Aust N Z J Surg 1999;69:632–4.

7. Moulton-Barrett R, Crumley R, Jalilie S, et al. Complications of thyroid surgery. Int Surg 1997;82:63–6.

8. Baba M, Natsugoe S, Shimada M, et al. Does hoarseness of voice from recurrent nerve paralysis after esophagectomy for carcinoma influence patient quality of life? J Am Coll Surg 1999;188:231–6.

9. Morris GL III, Mueller WM. Long-term treatment with vagus nerve stimulation in patients with refractory epilepsy. The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group E01-E05. Neurology 1999;53:1731–5.

10. Santos PM, Afrassiabi A, Weymuller EA Jr. Risk factors associated with prolonged intubation and laryngeal injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;111:453–9.

11. Mace SE. Blunt laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 1986;15:836–42.

12. Schaefer SD. The acute management of external laryngeal trauma. A 27-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;118:598–604.

13. Resouly A, Hope A, Thomas S. A rapid access husky voice clinic: useful in diagnosing laryngeal pathology. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115:978–80.

14. Johnson JT, Newman RK, Olson JE. Persistent hoarseness: an aggressive approach for early detection of laryngeal cancer. Postgrad Med 1980;67:122–6.

15. Hartl DA, Hans S, Vaissière J, et al. Objective acoustic and aerodynamic measures of breathiness in paralytic dysphonia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2003;260:175–82.

16. Faust RA. Childhood voice disorders: ambulatory evaluation and operative diagnosis. Clin Pediatr 2003;42:1–9.

17. Portier F, Marianowski R, Morisseau-Durand MP, et al. Respiratory obstruction as a sign of brainstem dysfunction in infants with Chiari malformations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2001;57:195–202.

18. Truong MT, Messner AH, Kerschner JE, et al. Pediatric vocal fold paralysis after cardiac surgery: rate of recovery and sequelae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137:780–4.

19. Dworkin JP. Laryngitis: types, causes, and treatments. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008;41:419–36, ix.

20. Wang CL, Cohan RH, Ellis JH, et al. Frequency, outcome, and appropriateness of treatment of nonionic iodinated contrast media reactions. Am J Roentgenol 2008;191:409–15.

21. Mortelé KJ, Oliva MR, Ondategui S, et al. Universal use of nonionic iodinated contrast medium for CT: evaluation of safety in a large urban teaching hospital. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:31–4.

22. Dillman JR, Ellis JH, Cohan RH, et al. Frequency and severity of acute allergic-like reactions to gadolinium-containing IV contrast media in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;189: 1533–8.

23. Chung SM. Safety issues in magnetic resonance imaging. J Neuroophthalmol 2002;22:35–9.

24. Stecco A, Saponaro A, Carriero A. Patient safety issues in magnetic resonance imaging: state of the art. Radiol Med 2007;112:491–508.

25. Quirk ME, Letendre AJ, Ciottone RA, et al. Anxiety in patients undergoing MR imaging. Radiology 1989;170:463–6.

26. Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms improve before changes in physical findings. Laryngoscope 2001;111:979–81.

27. El-Serag HB, Lee P, Buchner A, et al. Lansoprazole treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic laryngitis: a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:979–83.

28. Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope 2006;116: 254 – 60.

29. Hanlon JT, Landerman LR, Artz MB, et al. Histamine2 receptor antagonist use and decline in cognitive function among community dwelling elderly. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:781–7.

30. Ylitalo R, Ramel S. Extraesophageal reflux in patients with contact granuloma: a prospective controlled study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2002;111:441–6.

31. Park W, Hicks DM, Khandwala F, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: prospective cohort study evaluating optimal dose of proton-pump inhibitor therapy and pretherapy predictors of response. Laryngoscope 2005;115:1230–8.

32. Williams AJ, Baghat MS, Stableforth DE, et al. Dysphonia caused by inhaled steroids: recognition of a characteristic laryngeal abnormality. Thorax 1983;38:813–21.

33. Williamson IJ, Matusiewicz SP, Brown PH, et al. Frequency of voice problems and cough in patients using pressurized aerosol inhaled steroid preparations. Eur Respir J 1995;8:590–2.

34. Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000247. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub2.

35. Glasziou PP, Del Mar C, Sanders S, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000219. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD000219.pub2.

36. Horn JR, Hansten PD. Drug interactions with antibacterial agents. J Fam Pract 1995;41:81–90.

37. Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists. Clinical voice disorders. Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists; 2005. http://www.rcslt.org/resources/RCSLT_Clinical_Guidelines.pdf (accessed June 10, 2009).

38. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Preferred practice patterns for the profession of speech-language pathology. 2004. http://www.asha.org/docs/html/PP2004-00191.html.

39. Bastian RW, Levine LA. Visual methods of office diagnosis of voice disorders. Ear Nose Throat J 1988;67:363–79.

40. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. The use of voice therapy in the treatment of dysphonia. 2005. http://www.asha.org/ docs/html/TR2005-00158.html.

41. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Training guidelines for laryngeal videoendoscopy/stroboscopy. 1998. http://www.asha.org/docs/html/GL1998-00064.html.

42. Thomas G, Mathews SS, Chrysolyte SB, et al. Outcome analysis of benign vocal cord lesions by videostroboscopy, acoustic analysis and voice handicap index. Indian J Otolaryngol 2007;59:336–40.

43. Zeitels SM, Casiano RR, Gardner GM, et al. Management of common voice problems: committee report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;126:333–48.

44. Johns MM. Update on the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of vocal fold nodules, polyps, and cysts. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;11:456–61.

45. McCrory E. Voice therapy outcomes in vocal fold nodules: a retrospective audit. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2001;36(Suppl):19–24.

46. Havas TE, Priestley J, Lowinger DS. A management strategy for vocal process granulomas. Laryngoscope 1999;109:301–6.

47. Johns MM, Garrett CG, Hwang J, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes following laryngeal endoscopic surgery for non-neoplastic vocal fold lesions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2004;113:597–601

48. Sulica L. Contemporary management of spasmodic dysphonia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;12:543–8.

49. Stong BC, DelGaudio JM, Hapner ER, et al. Safety of simultaneous bilateral botulinum toxin injections for abductor spasmodic dysphonia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;131:793–5.

50. Troung DD, Rontal M, Rolnick M, et al. Double-blind controlled study of botulinum toxin in adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope 1991;101:630–4.

51. Cannito MP, Woodson GE, Murry T, et al. Perceptual analyses of spasmodic dysphonia before and after treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130:1393–9.

52. Courey MS, Garrett CG, Billante CR, et al. Outcomes assessment following treatment of spasmodic dysphonia with botulinum toxin. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2000;109:819–22.

53. Yiu EM, Chan RM. Effect of hydration and vocal rest on the vocal fatigue in amateur karaoke singers. J Voice 2003;17:216–27.

54. Jónsdottir V, Laukkanen AM, Siikki I. Changes in teachers’ voice quality during a working day with and without electric sound amplification. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2003;55:267–80.

55. Ruotsalainen JH, Sellman J, Lehto L, et al. Interventions for preventing voice disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006372. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

56. Duffy OM, Hazlett DE. The impact of preventive voice care programs for training teachers: a longitudinal study. J Voice 2004;18:63–70.

57. Bovo R, Galceran M, Petruccelli J, et al. Vocal problems among teachers: evaluation of a preventive voice program. J Voice 2007;21:705–22.