Acute Otitis Externa

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Otorhinolaryngology, Audiovestibular & Phoniatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | Acute Otitis Externa |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 9:12 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 April 2024"

- Committee

Chair

of the Panel:

Usama Abdel Naseer

Scientific Group Members:

Abdalla Anayet, Abdelrahman Eltahaan, Ahmed Mostafa, Alaa Gaafar, Amr Taha, Ashraf Lotfy, Athar Reda Ibrahim, Bahaa Eltoukhy, Haytham Elfarargy, Hazem Dewidar, Ihab Sifin, Loay Elsharkawy, Mai Mohammed Salama, Mina Esmat, Rania Abdou, Reda Sharkawy, Saad Elzayat, Samir Halim.

Abbreviations

AOE: Acute otitis externa

Glossary

Acute otitis externa (AOE) It is s diffuse inflammation of the external ear canal, which may also involve the pinna or tympanic membrane.

- Executive Summary

This Guideline is intended to provides evidence-based recommendations to manage acute otitis externa (AOE), defined as diffuse inflammation of the external ear canal, which may also involve the pinna or tympanic membrane. The variations in management of AOE and the importance of accurate diagnosis suggest a need for applying the clinical practice guideline. The primary outcome considered

in this guideline is clinical resolution of AOE

◾ Clinicians should distinguish diffuse acute otitis externa (AOE) from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation of the external ear canal.

◾ Clinicians should assess the patient with diffuse AOE for factors that modify management (nonintact tympanic membrane, tympanostomy tube, diabetes, immunocompromised state, priorradiotherapy).

◾ The clinician should assess patients with AOE for pain and recommend analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain.

◾ Clinicians should not prescribe systemic antimicrobials as initial therapy for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE unless there is extension outside the ear canal or the presence of specific host factors that would indicate a need for systemic therapy.

◾ Clinicians should use topical preparations for initial therapy of diffuse, uncomplicated AOE.

◾ Clinicians should inform patients how to administer topical drops and should enhance delivery of topical drops when the ear canal is obstructed by performing aural toilet, placing a wick, or both.

◾ When the patient has a known or suspected perforation of the tympanic membrane, including a tympanostomy tube, the clinician should recommend a non-ototoxic topical preparation.

◾ If the patient fails to respond to the initial therapeutic option within 48 to 72 hours, the clinician should reassess the patient to confirm the diagnosis of diffuse AOE and to exclude other causes of illness.

- Introduction

The diagnosis of diffuse AOE requires rapid onset (generally within 48 hours) in the past 3 weeks of symptoms and signs of ear canal inflammation, as detailed in Table 4. A hallmark sign of diffuse AOE is tenderness of the tragus, pinna, or both that is often intense and disproportionate to what might be expected based on visual inspection.

The continued variations in managing AOE and the importance of accurate diagnosis suggest a need for this evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Failure to distinguish AOE from other causes of “the draining ear” (eg, chronic external otitis, malignant otitis externa, middle ear disease, cholesteatoma) may prolong morbidity or cause serious complications.

Because topical therapy is efficacious, systemic antibiotics are often prescribed inappropriately. When topical therapy is prescribed, confusion exists about whether to use an antiseptic (eg, acetic acid), antibiotic, corticosteroid, or a combination product. Antibiotic choice is controversial, particularly regarding the role of newer quinolone drops. Lastly, the optimal methods for cleaning the ear canal (aural toilet) and drug delivery are defined.

The primary outcome considered in this guideline is clinical resolution of AOE, which implies resolution of all presenting signs and symptoms (eg, pain, fever, otorrhea). Additional outcomes considered include minimizing the use of ineffective treatments; eradicating pathogens; minimizing recurrence, cost, complications, and adverse events; maximizing the health-related quality of life of individuals afflicted with AOE; increasing patient satisfaction ; and permitting the continued use of necessary hearing aids. The relatively high incidence of AOE and the diversity of interventions in practice (Table 5) make AOE an important condition for the use of an up-to-date, evidence-based practice guideline.

➡️Purpose

The primary purpose of the guideline is to promote appropriate use of oral and topical antimicrobials for AOE and to highlight the need for adequate pain relief.

This guideline does not apply to children younger than 2 years or to patients of any age with chronic or malignant (progressive necrotizing) otitis externa. AOE is uncommon before 2 years of age, and very limited evidence exists regarding treatment or outcomes in this age group. Although the differential diagnosis of the “draining ear” will be discussed, recommendations for management will be limited to diffuse AOE, which is almost exclusively a bacterial infection. The following conditions will be briefly discussed but not considered in detail: furunculosis (localized AOE), otomycosis, herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), and contact dermatitis.

➡️The target audience

The guideline is intended for primary care and specialist clinicians, including otolaryngologists -head and neck surgeons, pediatricians, family physicians, emergency physicians, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. The guideline is applicable to any setting in which children, adolescents, or adults with diffuse AOE would be identified, monitored, or managed.

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

inclusion/exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

◾ Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

◾ Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

◾ Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2013 and later)

◾ Selecting peer reviewed publications only

◾ Selecting guidelines written in English language

◾ Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input

◾ Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

• Developing organisation/authors

• Date of publication, posting, and release

• Country/language of publication

• Date of posting and/or release

• Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. the panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 50% on the rigour dimension was retained)

➡️Evidence assessment

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

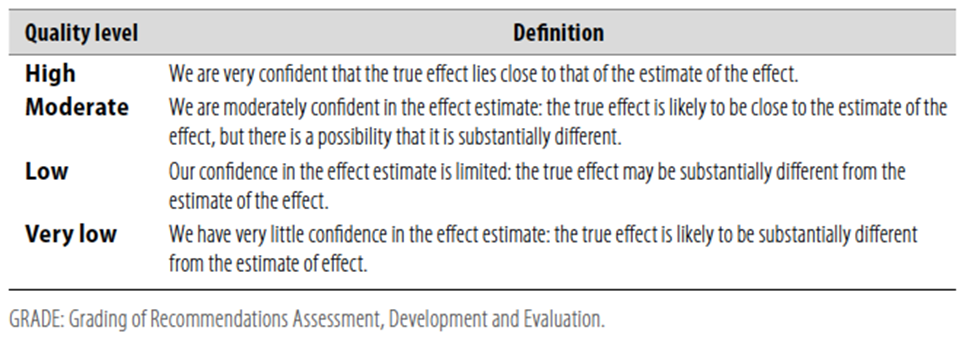

Table 1 Quality of evidence in GRADE

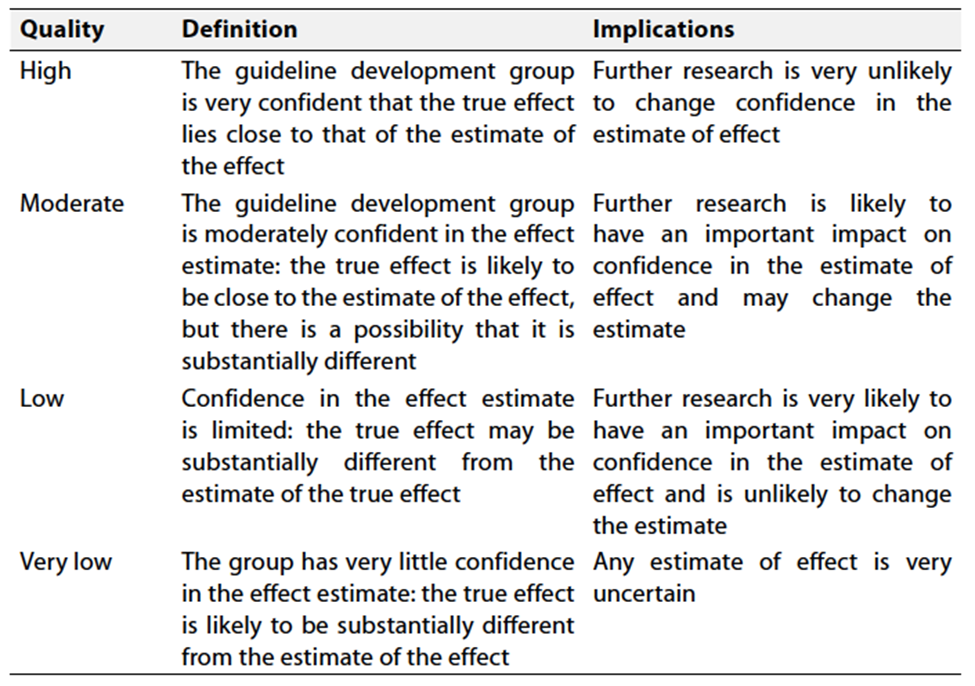

Table 2 Significance of the four levels of evidence

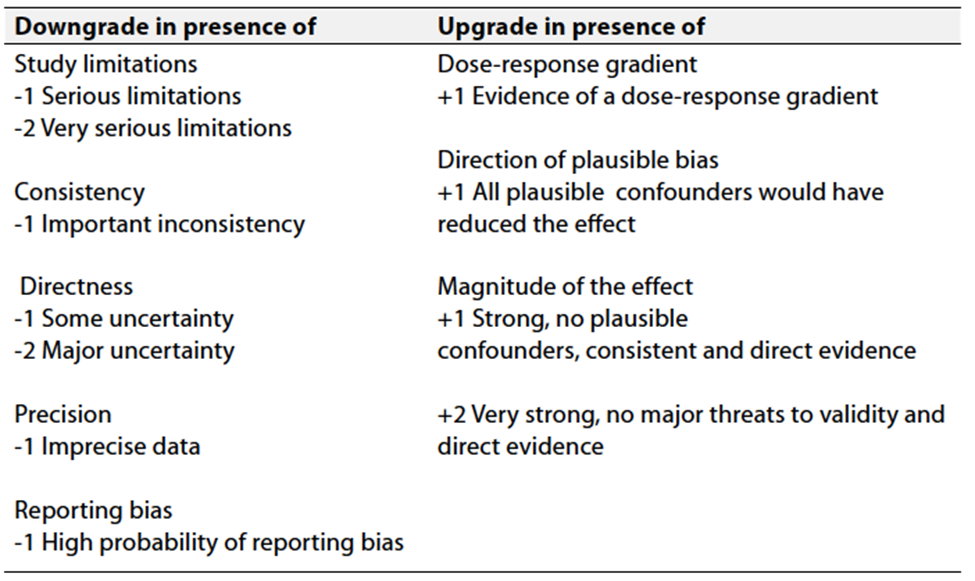

Table 3 Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of evidence

- The strength of the recommendation

The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

➡️Strong recommendations

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

➡️Conditional recommendations

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

When not to make recommendations

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

- Recommendations

1. Differential diagnosis:Clinicians should distinguish diffuse acute otitis externa (AOE) from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation of the external ear canal. Strong recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk)2,3 |

2. Modifying factors:Clinicians should assess the patient with diffuse AOE for factors that modify management (non-intact tympanic membrane, tympanostomy tube, diabetes, immunocompromised state, prior radiotherapy). ➡️Strong recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over risk)4-8 |

3. Pain management:The clinician should assess patients with AOE for pain and recommend analgesic treatment based on the severity of pain.. ➡️Strong Recommendation Hihg Quality Evidence (based on well-designed randomized trials with a preponderance of benefit over harm)9-19 |

4. Systemic antimicrobials:Clinicians should not prescribe systemic antimicrobials as initial therapy for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE unless there is extension outside the ear canal or the presence of specific host factors that would indicate a need for systemic therapy. ➡️Strong Recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on randomized controlled trials with minor limitations and a preponderance of benefit over harm)20-25 |

5. Topical therapy:Clinicians should use topical preparations for initial therapy of diffuse, uncomplicated AOE. ➡️Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on randomized trials with some heterogeneity and a preponderance of benefit over harm)26-28 |

6. Drug delivery:Clinicians should inform patients how to administer topical drops and should enhance delivery of topical drops when the ear canal is obstructed by performing aural toilet, placing a wick, or both. ➡️Strong Recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm)29.30 |

7. Nonintact tympanic membrane:When the patient has a known or suspected perforation of the tympanic membrane, including a tympanostomy tube, the clinician should recommend a non-ototoxic topical preparation. ➡️Conditional recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (based on reasoning from first principles and on exceptional circumstances in which validating studies cannot be performed and there is a preponderance of benefit over harm.)31-35 |

8. Outcome assessment:If the patient fails to respond to the initial therapeutic option within 48 to 72 hours, the clinician should reassess the patient to confirm the diagnosis of diffuse AOE and to exclude other causes of illness. ➡️Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (based on observational studies and a preponderance of benefit over harm)36-38 Clinical Indicators for Monitoring |

1. Through proper history and examination, Clinicians should accurately distinguish diffuse AOE from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation of the external ear canal during initial patient assessment.

2. Evaluate Modifying Factors such as a nonintact tympanic membrane, tympanostomy tube, diabetes, immunocompromised state that may have effect on the condition.

3. Avoid prescribing systemic antimicrobials as the initial therapy for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE unless specific conditions, such as extension outside the ear canal or particular host factors exist.

4. Adhere to the recommendation of using topical preparations as the primary therapeutic option for diffuse, uncomplicated AOE and take additional measures, such as aural toilet, wick placement, or both, to enhance delivery when the ear canal is obstructed.

➡️ Updating the guideline

To keep these recommendations up to date and ensure its validity it will be periodically updated. This will be done whenever a strong new evidence is available and necessitates updation.

➡️Research Needs

1. RCTs of absolute and comparative clinical efficacy of ototopical therapy of uncomplicated AOE in primary care settings, including the impact of aural toilet on outcomes

2. Clinical trials to determine the efficacy of topical steroids for relief of pain caused by AOE.

3. Observational studies or clinical trials to determine if water precautions are necessary, or beneficial, during treatment of an active AOE episode.

4. Comparative clinical trials of “home therapies” (eg, vinegar, alcohol) versus antimicrobials for treating AOE.

- References

1. Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Cannon CR, Roland PS, Simon GR, Kumar KA, Huang WW, Haskell HW, Robertson PJ. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Feb;150(1 Suppl):S1-S24. doi: 10.1177/0194599813517083. Erratum in: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Mar;150(3):504. Erratum in: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Mar;150(3):504. PMID: 24491310.

2. Lucente FE, Lawson W, Novick NL. External Ear. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1995.

3. Lieberthal AS, Ganiats TG, Cox EO, et al. Clinical practice guideline: American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media: diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451-1465.

4. Timon CI, O’Dwyer T. Diagnosis, complications, and treatment of malignant otitis externa. Ir Med J. 1989;82(1):30-31.

5. Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, Agarwal S. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127(2):194-205.

6. Phillips P, Bryce G, Shepherd J, Mintz D. Invasive external otitis caused by Aspergillus. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(2):277-281.

7. Hern JD, Almeyda J, Thomas DM, Main J, Patel KS. Malignant otitis externa in HIV and AIDS. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110(8):770-775.

8. Wolff LJ. Necrotizing otitis externa during induction therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatrics. 1989;84(5):882-885.

9. Schechter NL, Berde CM, Yaster M. Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993.

10. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations. Pain: Current Understanding of Assessment, Management and Treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council & JCAHO. 2001. http://www.JCAHO.org. Accessed August 22, 2005.

11. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):793-797.

12. Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41(2):139-150.

13. Beyer JE, Knott CB. Construct validity estimation for the African-American and Hispanic versions of the Oucher Scale. J Pediatr Nurs. 1998;13(1):20-31.

14. Powell CV, Kelly AM, Williams A. Determining the minimum clinically significant difference in visual analog pain score for children. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(1):28-31.

15. Loesser JD. Bonica’s Management of Pain. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

16. Valencia CG, Valencia PG. Potassium diclofenac vs. placebo in acute otitis externa: a double-blind, comparative study [in Spanish]. Invest Med Int. 1987;14:56-60.

17. Zeltzer LK, Altman A, Cohen D, LeBaron S, Munuksela EL, Schechter NL. American Academy of Pediatrics Report of the Subcommittee on the Management of Pain Associated with Procedures in Children with Cancer. Pediatrics. 1990;86(5, pt 2):826-831.

18. Premachandra DJ. Use of EMLA cream as an analgesic in the management of painful otitis externa. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104(11):887-888.

19. MedlinePlus. Antipyrine-benzocaine otic. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/ medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a607073.html. Accessed November 19, 2013.

20. Cannon SJ, Grunwaldt E. Treatment of otitis externa with a tropical steroid-antibiotic combination. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46(10):1296-1302.

21. Cannon S. External otitis: controlled therapeutic trial. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1970;49(4):186-189.

22. Freedman R. Versus placebo in treatment of acute otitis externa. Ear Nose Throat J. 1978;57(5):198-204.

23. Yelland MJ. The efficacy of oral cotrimoxazole in the treatment of otitis externa in general practice. Med J Aust. 1993;158(10):697-699.

24. Pottumarthy S, Fritsche TR, Sader HS, Stilwell MG, Jones RN. Susceptibility patterns of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in North America (2002-2003): contemporary in vitro activities of amoxicillin/clavulanate and 15 other antimicrobial agents. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25(4):282-289.

25. Kime CE, Ordonez GE, Updegraff WR, Glassman JM, Soyka JP. Effective treatment of acute diffuse otitis externa: II. A controlled comparison of hydrocortisone-acetic acid, nonaqueous and hydrocortisone-neomycin-colistin otic solutions. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1978;23(suppl 5):ss3-ss14.

26. Rosenfeld RM, Singer M, Wasserman JM, Stinnett SS. Systematic review of topical antimicrobial therapy for acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(4 suppl):S24-48.

27. Kaushik V, Malik T, Saeed SR. Interventions for acute otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(1):CD004740.

28. Mösges R, Nematian-Samani M, Hellmich M, Shah-Hosseini K. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of quinolone containing otics in comparison to antibiotic-steroid combination drugs in the local treatment of otitis externa. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):2053-2060.

29. England RJ, Homer JJ, Jasser P, Wilde AD. Accuracy of patient self-medication with topical eardrops. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114(1):24-25.

30. Agius AM, Reid AP, Hamilton C. Patient compliance with short-term topical aural antibiotic therapy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19(2):138-141.

31. Russell PT, Church CA, Jinn TH, Kim DJ, John EO, Jung TT. Effects of common topical otic preparations on the morphology of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121(2):135-139.

32. Jinn TH, Kim PD, Russell PT, Church CA, John EO, Jung TT. Determination of ototoxicity of common otic drops using isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(12):2105-2108.

33. Roland PS, Rybak L, Hannley M, et al. Animal ototoxicity of topical antibiotics and the relevance to clinical treatment of human subjects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3 suppl):S57-S78.

34. Roland PS, Stewart MG, Hannley M, et al. Consensus panel on role of potentially ototoxic antibiotics for topical middle ear use: introduction, methodology, and recommendations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3 suppl):S51-S56.

35. Committee on Safety of Medicines and the Medicines Control Agency. Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance. Vol 23, December 1997:14.

36. van Balen FA, Smit WM, Zuithoff NP, Verheij TJ. Clinical efficacy of three common treatments in acute otitis externa in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1201-1205.

37. Emgard P, Hellstrom S. A group III steroid solution without antibiotic components: an effective cure for external otitis. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(5):342-347.

38. Torum B, Block SL, Avila H, et al. Efficacy of ofloxacin otic solution once daily for 7 days in the treatment of otitis externa: a multicenter, open-label, phase III trial. Clin Ther. 2004;26(7):1046-1054.

- Annexes

Table 4. Elements of the diagnosis of diffuse acute otitis externa. |

1. Rapid onset (generally within 48 hours) in the past 3 weeks, AND… 2. Symptoms of ear canal inflammation, which include: otalgia (often severe), itching, or fullness, WITH OR WITHOUT hearing loss or jaw pain, a AND… 3. Signs of ear canal inflammation, which include: tenderness of the tragus, pinna, or both OR diffuse ear canal edema, erythema, or both WITH OR WITHOUT otorrhea, regional lymphadenitis, tympanic membrane erythema, or cellulitis of the pinna and adjacent skin |

a Pain in the ear canal and temporomandibular joint region intensified by jaw motion. |

Table 5. Interventions considered in acute otitis externa guideline development. |

➡️Diagnosis ▪️ History and physical examination ▪️ Otoscopy ▪️ Pneumatic otoscopy ▪️ Otomicroscopy ▪️ Tympanometry ▪️ Acoustic reflectometry ▪️ Culture ▪️ Imaging studies ▪️ Audiometry (excluded from guideline) ➡️Treatment ▪️ Aural toilet (suction, dry mopping, irrigation, removal of obstructing cerumen or foreign object) ▪️ Non-antibiotic (antiseptic or acidifying) drops ▪️ Antibiotic drops ▪️ Steroid drops ▪️ Oral antibiotics ▪️ Analgesics ▪️ Complementary and alternative medicine ▪️ Ear canal wick ▪️ Biopsy (excluded from guideline) ▪️ Surgery (excluded from guideline) ➡️Prevention ▪️ Water precautions ▪️ Prophylactic drops ▪️ Environmental control (eg, hot tubs) ▪️ Avoiding neomycin drops (if allergic) ▪️ Addressing allergy to ear molds or water protector ▪️ Addressing underlying dermatitis ▪️ Specific preventive measures for diabetics or ▪️ immunocompromised state |

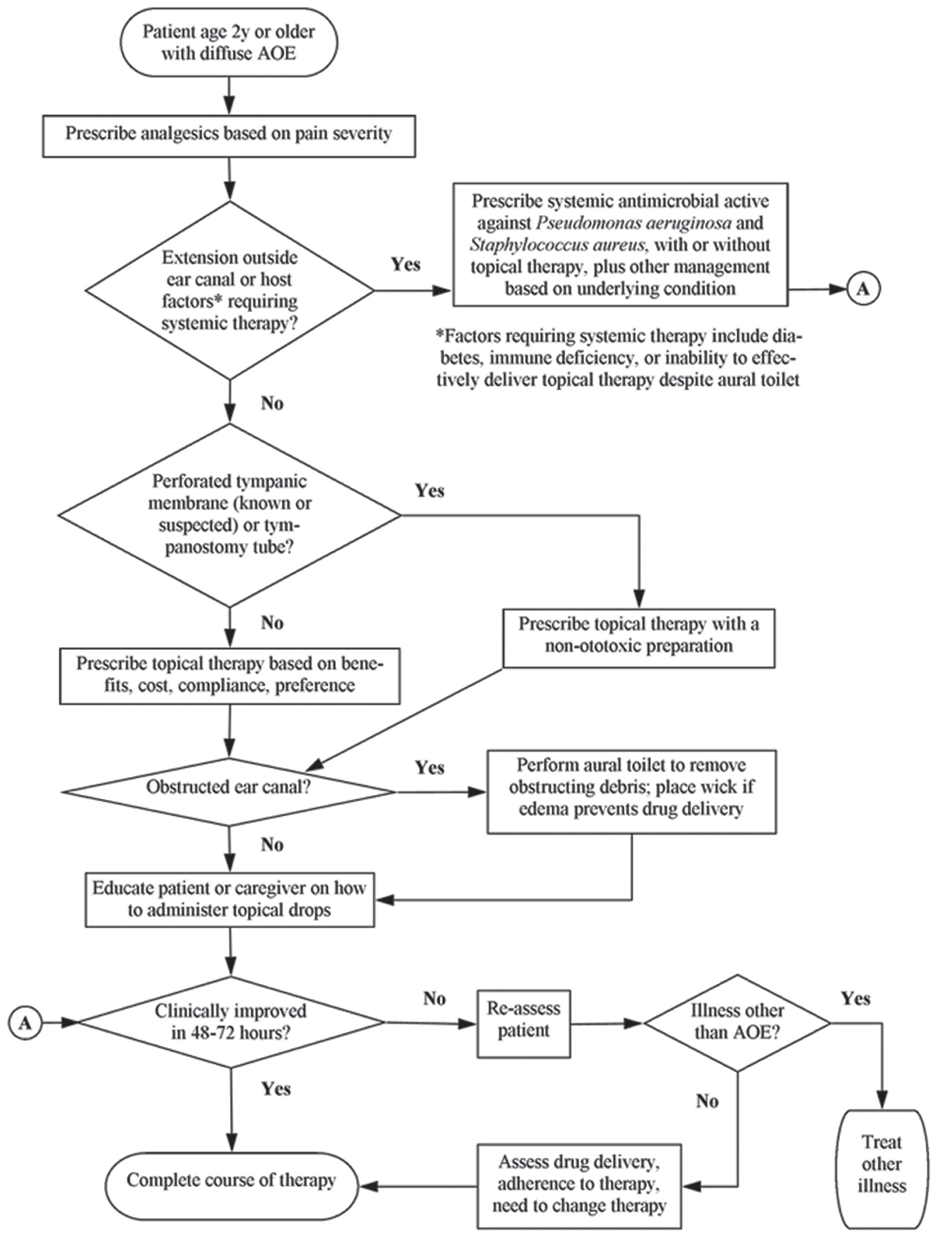

Figure 1: Flow chart for managing acute otitis externa.