Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional Edema (Acute Malnutrition) in Infants and Children Under 5 Years

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Pediatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | Prevention and Management of Wasting and Nutritional Edema (Acute Malnutrition) in Infants and Children Under 5 Years |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 10:22 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 April 2024"

- Committee

|

Egyptian Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (EPG) Guideline Adaptation Group (Clinical subgroup) |

|||||

|

Name |

Affiliation, Area of expertise / Country / Primary location [work] |

Contribution |

|||

|

Prof. Sahar Khairy |

Professor of Pediatrics Dean of National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

Obtaining WHO approval, revision of the final draft, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Prof. Sanaa Yousef |

Professor of Pediatrics Ain Shams University, Egypt |

Writing introduction, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Prof. Dina Shehab |

Professor of Pediatrics, Clinical Nutrition Consultant, and previous Head of Clinical Nutrition Department, National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

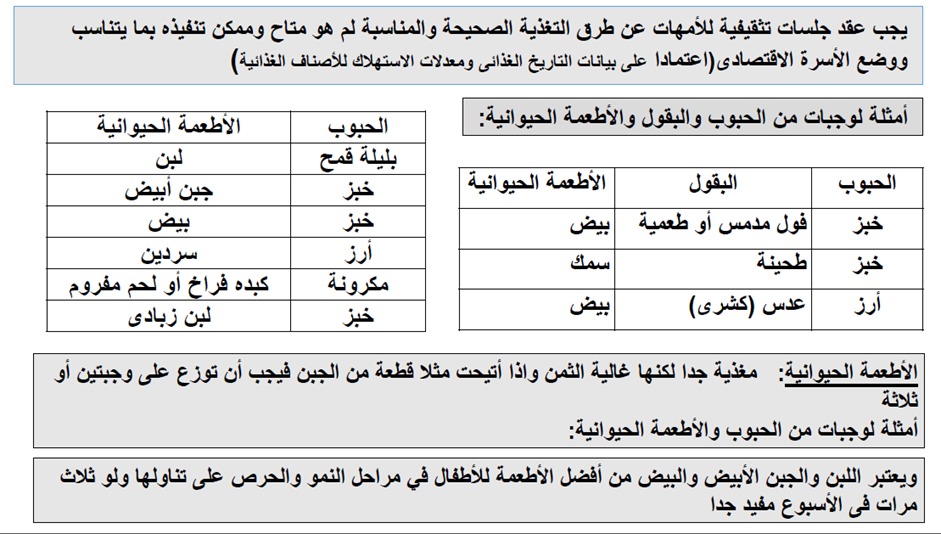

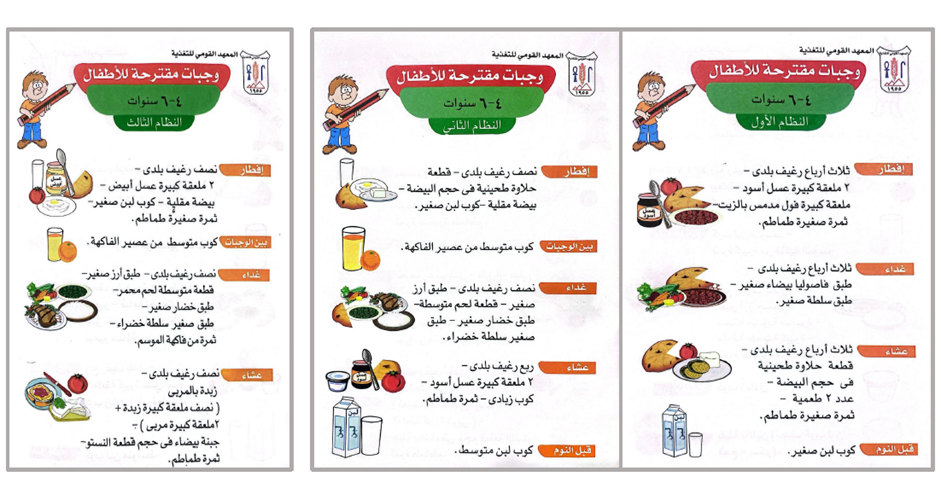

Development of the implementation tools and Arabic nurses and mothers’ education guide, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Prof. Hoda Ahmed Atwa |

professor and Head of Pediatrics Department, Suez Canal University |

Writing introduction, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Prof. Yasmin Gamal El Gendy |

Associate professor of pediatrics, Ain Shams university |

Writing introduction and scope, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Prof. Eman Habib |

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Clinical Nutrition Consultant, Head of Clinical Nutrition Department, National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Dr. Enas Sayed Abbas |

Lecturer of Pediatrics & Clinical Nutrition Consultant, IBCLC National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

Development of the implementation tools and Arabic nurses and mothers’ education guide and Writing introduction, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Dr. Enas Mohamed Fawzy Mowafy

|

MD Pediatrics, Nutritionist, Head of Statistics Unit, National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

Appraisal of WHO guideline, writing executive summary, collecting GDG comments, reviewing and adaptation of WHO guideline |

|||

|

Egyptian Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (EPG) Guideline Adaptation Group (Methodology subgroup) |

|||||

|

Name |

Affiliation, Area of expertise / Country / Primary location [work] |

Contribution |

|||

|

Prof. Ashraf Abdel Baky |

Professor of Pediatrics Ain Shams University, Egypt Chair of EPG |

Overseeing the adolopment process of the guidelines, revision of the final draft, Organizing weekly online meetings of GDG |

|||

|

AssociateProfessor of Pediatrics Ain Shams University, Egypt |

Develop evidence to decision tables of the adaptation, participated in search and appraisal of guidelines |

||||

|

Dr Lamis Mohsen |

Lecturer of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Modern University forTechnology and Information (MTI), Egypt |

Participated in documentation of GDG meetings and in Methodology revision |

|||

|

Dr Ahmed Youssef |

Lecturer of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Modern University for Technology and Information (MTI), Egypt The General Organization for Teaching Hospitals and Institutes |

Participated in Writing the methodology of adaptation process and revised the whole document. |

|||

|

Dr Nahla Gamaleldin |

Lecturer of pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Modern University for Technology and Information (MTI), Egypt |

Participated in search and retrieved guidelines appraisal and revision of the document |

|||

|

Dr Mona Saber |

Lecturer of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Modern University for Technology and Information (MTI), Egypt |

Participated in search and retrieved guidelines appraisal and revision of the document |

|||

|

Guideline Adaptation Group (External Reviewers subgroup) |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Prof. Osama Al-Eshery |

Professor of Pediatrics, Assiut University, Egypt |

||||

|

Prof. Sahar Ali |

Professor of Pediatrics, National Nutrition Institute, Egypt |

||||

|

International Peer Reviewers |

|||||

|

|

WHO |

||||

|

|

UNICEF |

||||

|

External Reviewer for methodology |

|||||

|

Dr Yasser Samy |

Chair, Adaptation working Group, Guidelines International Network, Scotland. Pediatrics Department and Clinical Practice Guidelines Unit, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. |

||||

- Acknowledgements

|

|

▪️ The GDG acknowledge National Nutrition Institute for leading this ambitious project and for its team major contribution in the development of the implementation tools and Arabic nurses and mothers’ education guide along with working with other group members in this guideline. ▪️ We also acknowledge the academic members in the GDG for their great role in adaptation, modification, and development of this guideline with addition of their clinical experience. ▪️ The GDG acknowledge EPG for their help in completing this project. ▪️ We acknowledge WHO guidelines for their cooperation in providing the permission in adapting our guidelines. ▪️ Finally, we wish the best for all our patients and their families who inspired us. It is for them this work is being finalized. Funding▪️ This work is not related to any pharmaceutical company. The members of the guideline’s adaptation group and their institute and universities volunteered their participation. |

- Abbreviations

|

- Glossary

Admission

Admission, for the purpose of this guideline, refers to a child being registered and entering inpatient care as a patient. This is distinguished from the term “enrolment”, which is used for outpatient care.

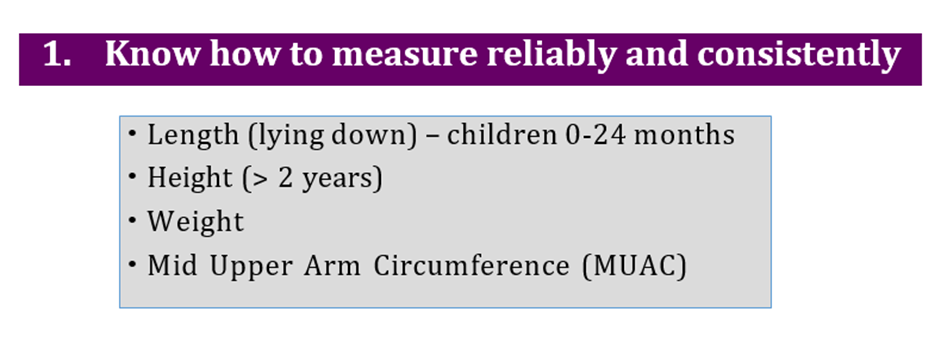

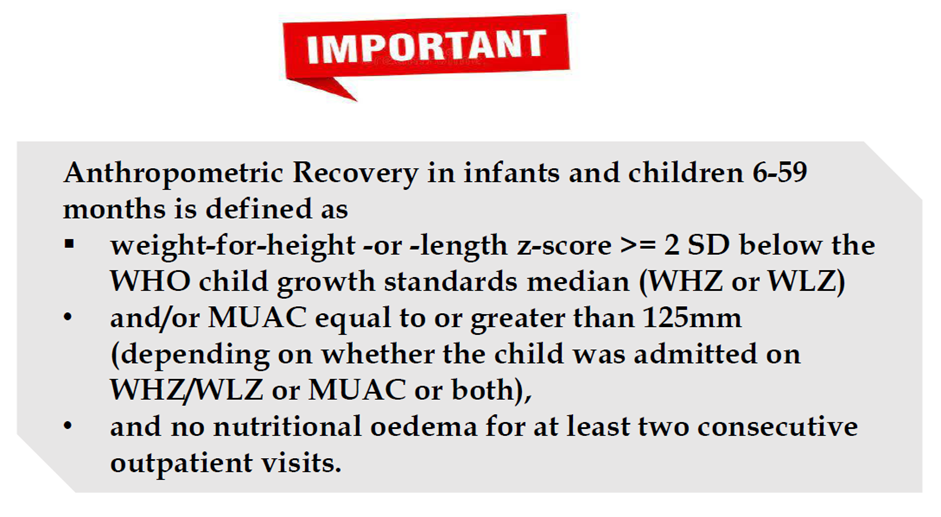

Anthropometric recovery

For the purpose of this guideline, this refers to weight-for-height (WHZ)/weight-for-length (WLZ) z-score equal to or greater than 2 standard deviations (SD) below the WHO child growth standards median (WHZ or WLZ ≥ -2) and a mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) equal to or greater than 125mm (in children 6-59 months) observed for at least 2 consecutive outpatient care visits. Before any decisions can be made regarding exit from nutritional treatment these anthropometric measurements need to be accompanied by an assessment of nutritional edema: a child must also be free of nutritional edema for at least two consecutive visits to meet exit criteria.

Caregiver

For the purpose of this guideline, a caregiver refers to a person, often a family member, who provides direct and regular care and support to an infant or child. This term is used in this guideline to emphasize that the father and other family members or non-related people can play a vital role in looking after children, in addition to (or even instead of) the mother; this may be even more relevant as the child grows older and is less likely to be breastfed.

Discharge

For the purpose of this guideline, discharge refers to a child finishing their inpatient care and leaving to go back home. This is distinguished from the term “exit” which is used for outpatient care.

Enrolment

For the purpose of this guideline, enrolment refers to a child being registered into outpatient care where nutritional supplementation or treatment is provided on a regular basis (see outpatient care). This is different to the term “admission” which is used for inpatient care.

Exit

For the purpose of this guideline, exit refers to a child finishing their nutritional treatment or supplementation and no longer attending outpatient care. This is distinguished from the term “discharge” which is used for inpatient care.

Health professionals

Health professionals’ study, advise on or provide preventive, curative, rehabilitative and promotional health services based on an extensive body of theoretical and factual knowledge in diagnosis and treatment of disease and other health problems. They may conduct research on human disorders and illnesses and ways of treating them and supervise other workers. The knowledge and skills required are usually obtained as the result of study at a higher educational institution in a health-related field for a period of 2–7 years leading to the award of a first degree or higher qualification. Health professionals include doctors, nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, dentists, paramedical practitioners.

Health workers

Health workers make up the health workforce and are people engaged to deliver health care to individuals and populations as part of the health system. Health workers are divided up into five main categories: health professionals, health associate professionals, personal care workers in health services, health management and support personnel, and other health service providers not elsewhere classified.

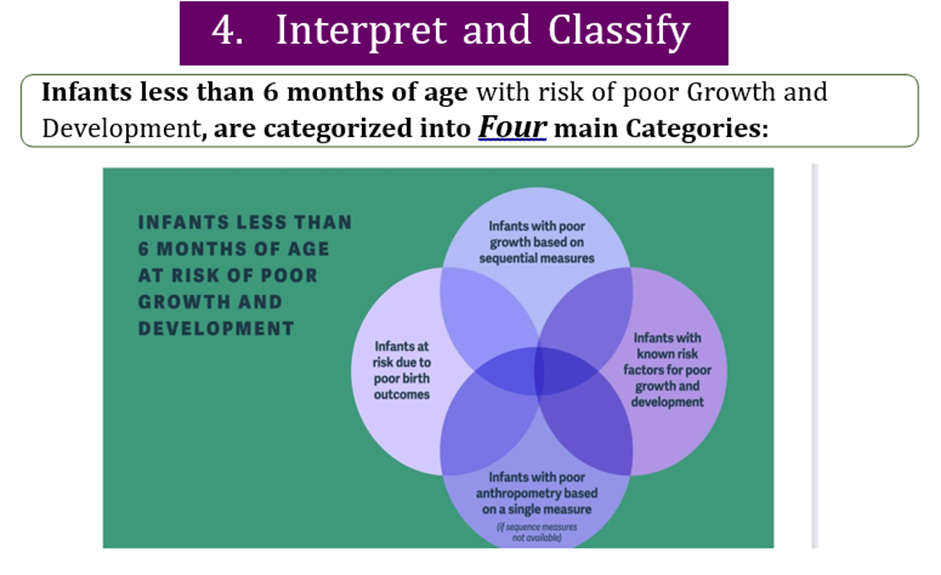

Infants at risk of poor growth & development

Infants less than 6 months who are not growing well before they meet the criteria of wasting and/or nutritional edema.

Inpatient care

For the purpose of this guideline, inpatient care refers to medical care, nutritional supplementation or treatment, and feeding support (for both breastfed and non-breastfed infants) which is delivered in a health facility involving the child staying for one or more nights in the health facility itself.

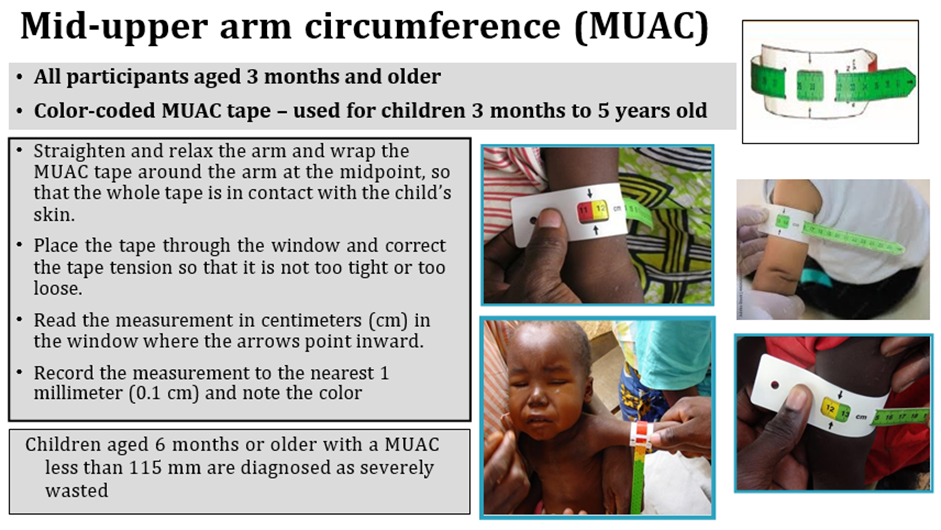

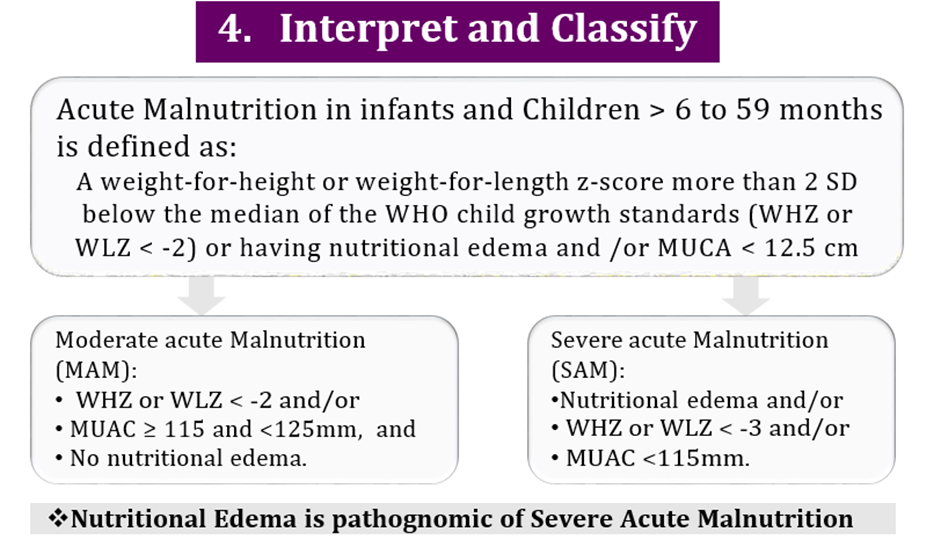

Moderate acute malnutrition (MAM)

- WHZ or WLZ < -2 and/or

- MUAC ≥ 115 and <125mm and

- No nutritional edema.

Mother/caregiver-infant

This term is used predominantly in relation to infants less than 6 months of age to highlight the importance of providing services for the mother/caregiver-infant pair together with a holistic approach encompassing all their physical and mental health and nutrition needs and recognizing the interdependence of this unit, especially in the early months of an infant’s life.

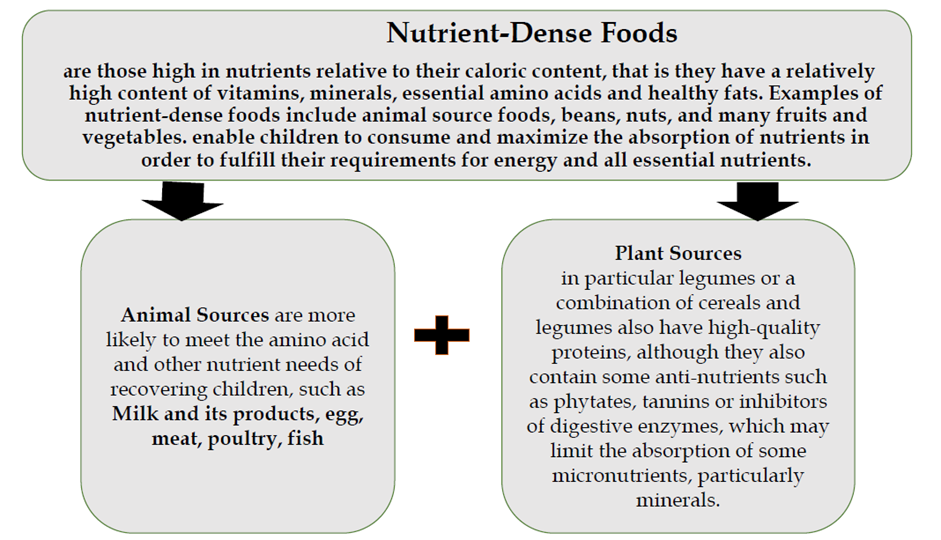

Nutrient-dense foods

Nutrient-dense foods are those high in nutrients relative to their caloric content that is they have a relatively high content of vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids and healthy fats. Examples of nutrient-dense foods include animal-source foods, beans, nuts, and many fruits and vegetables.

Nutritional supplementation (for moderate wasting)

For the purposes of this guideline, nutritional supplementation is used to describe the regular outpatient services, whereby infants and children with moderate wasting receive medical care and nutritional supplementation to achieve clinical and anthropometric recovery, as well as referring them to ongoing appropriate preventative and supportive services if needed and possible.

Nutritional treatment (for severe wasting and/or nutritional edema)

For the purpose of this guideline, nutritional treatment is used to describe the regular outpatient services, and potentially inpatient services (if needed), whereby infants and children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema receive therapeutic milk or ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) to help achieve anthropometric recovery and the resolution of nutritional edema. Nutritional treatment should always be delivered alongside medical care and referral to appropriate preventive and supportive services as needed.

Outpatient care

For the purpose of this guideline, outpatient care refers to medical care, nutritional supplementation or treatment (for children 6-59months) and feeding support (for both breastfed and non-breastfed infants) which is delivered in a health facility, and which does not require an overnight stay, but involves regular appointments (often referred to as visits) with a health worker until the child reaches clinical and anthropometric recovery. This health worker could be a health professional such as a doctor or nurse, or a health associate professional such as a community health care worker.

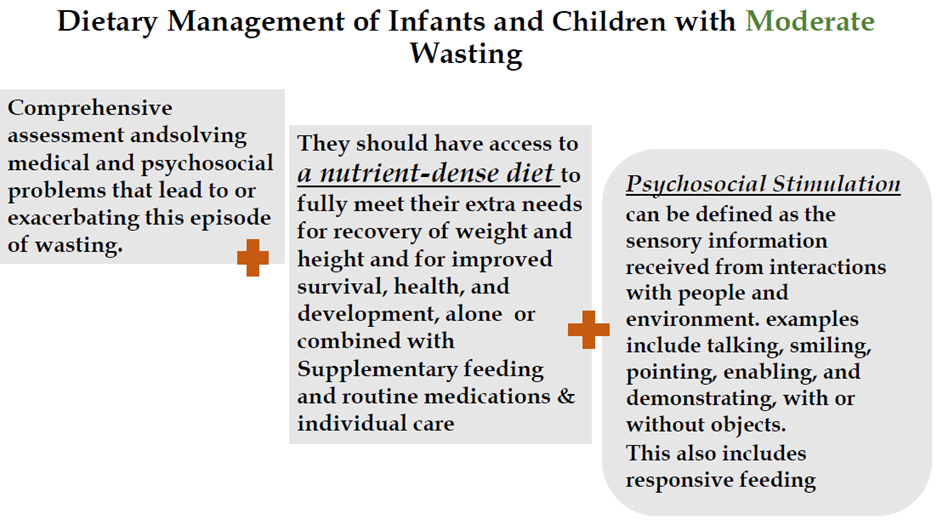

Psychosocial stimulation

Psychosocial stimulation can be defined as the sensory information received from interactions with people and environmental variability that engages a young child’s attention and provides information; examples include talking, smiling, pointing, enabling, and demonstrating, with or without objects. This also includes responsive feeding as a part of responsive caregiving.

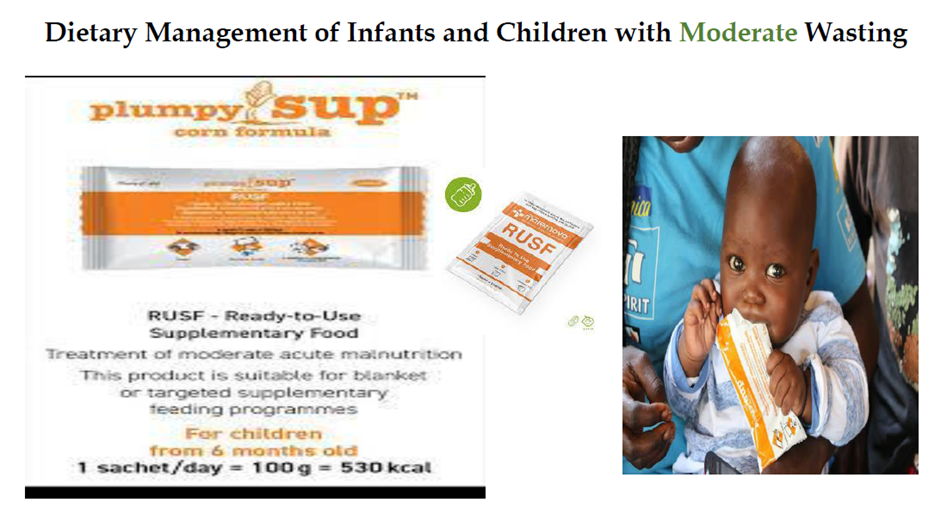

Ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF)

RUSF is a fortified lipid-based paste/spread used for the supplementation of children with moderate wasting. It should not be used for the nutritional treatment of severe wasting and/or nutritional edema.

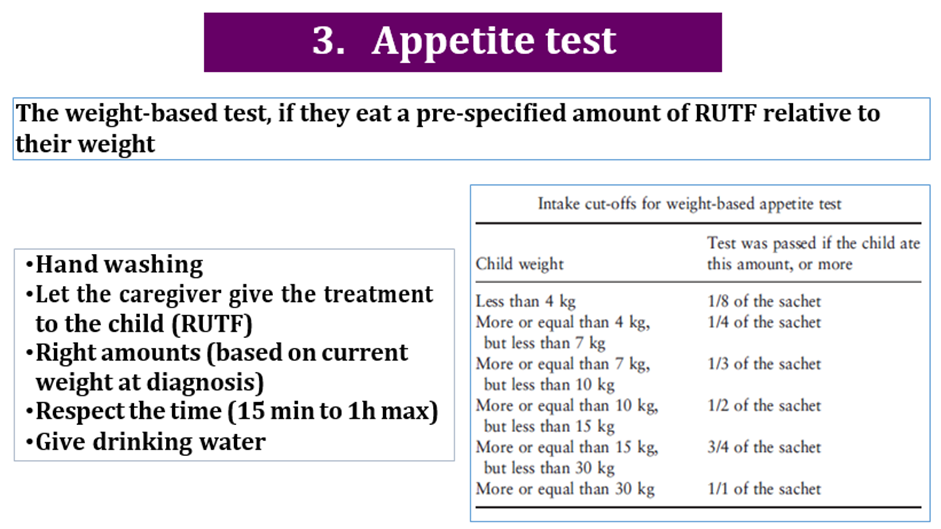

Ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF)

RUTF is a food for special medical purposes (Codex Alimentarius) and includes pastes/spreads and compressed biscuits/bars used for the nutritional treatment of children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema.

Referral

Referral, for the purpose of this guideline, refers predominantly to a child being referred to inpatient care from outpatient care. A malnourished child might however also get referred to other services such as HIV or TB (tuberculosis) care) for follow-up.

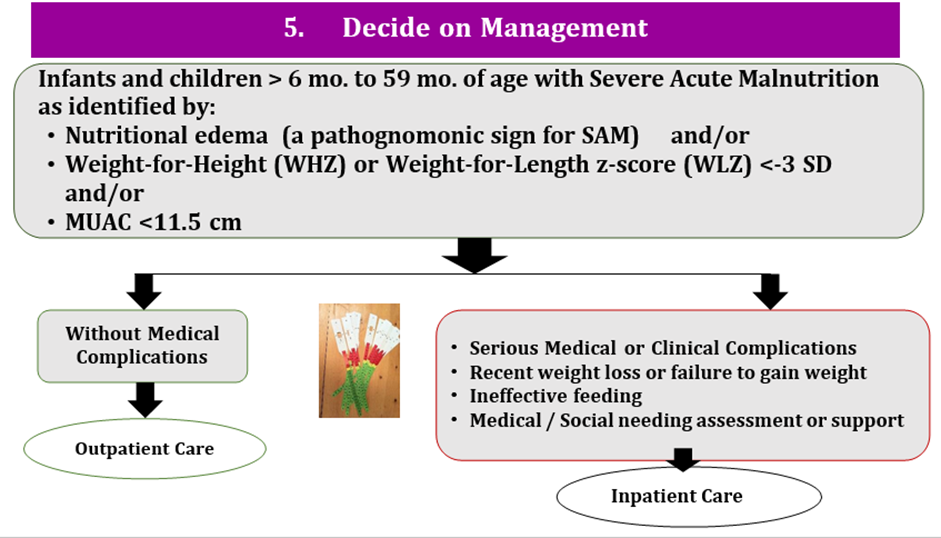

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM)

- Nutritional edema and/or

- WHZ or WLZ < -3 and/or

- MUAC <115mm

Specially formulated foods (SFFs)

For the purpose of this guideline, specially formulated foods are defined as foods that have been specifically designed, manufactured, distributed, and used for either: special medical purposes or for special dietary uses, as defined by Codex Alimentarius.

Transfer (from inpatient to outpatient care)

For the purpose of this guideline, transfer describes the patient movement when a child is discharged from inpatient care to finish their nutritional treatment in outpatient care. They usually go home from the hospital and then attend an outpatient center/clinic for nutritional treatment at a later date and then regularly until clinical and anthropometric recovery.

- Executive Summary

|

➡️Introduction There is rising risk of wasting and nutritional edema in infants and children, especially in high-risk contexts and ongoing crises as climate change and regional conflicts with expected increase of numbers of refugees, where health and socioeconomic factors are the poorest. Despite that the national prevalence of wasting in under 5 children is 3% in 2021, there is higher prevalence in some Egyptian governorates, as South Sinai 15.9%, Aswan 14.1%, Suez 10.7%, Luxor 8.8%, Qalioubiya 6.8%, Cairo 5.4%, Giza 4.8% and Assuit 4.5%. This guideline is adapted with permission from “WHO guideline on the prevention and management of wasting and nutritional edema (acute malnutrition) in infants and children under 5 years 2023”and “WHO guideline updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children 2013” to help in achieving global targets for wasting and nutritional edema including Sustainable Development Goal 2 to reach “Zero Hunger” by 2030. ➡️Scope This guidelinefocusses on prevention and management of acute malnutrition in under five infants and children with special consideration of infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development, moderate wasting in infants and children 6-59 months of age, severe wasting and nutritional edema in infants and children 6-59 months of age, and prevention of wasting and nutritional edema from a child health perspective. ➡️Guideline development process and methods After reviewing all the inclusion and exclusion criteria the GDG & methodologists recommended using 2 guidelines: 1- WHO guideline updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children (2013) 2- WHO guideline on the prevention and management of wasting and nutritional edema (acutemalnutrition) in infants and children under 5 years (2023) We did Adolopment for these guidelines: (Adoption, Adaptation, and Development) - Adoption for most of the guideline recommendations. - Adaptation for 2 recommendation according to GRADE criteria to be suitable to our Economic implications (Evidence to Decision (EtD) table was done) - Development of Good Practice Statement Recommendations and good practice statements This version of the guideline includes recommendations and good practice statements on the following four sub-sections: A. Management of infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development The guideline covers infants less than 6 months who are not growing well, before they meet criteria for wasting and/or nutritional edema and consider the mother and infant as an interdependent unit. This guideline emphasis on early identification and then provide appropriate immediate care or referral for both the infant and the mother/caregiver preventing later wasting and/or nutritional edema. This section includes recommendations and good practice statements on interventions for mothers/caregivers of infants at risk of poor growth and development, admission, referral, transfer, and exit criteria for infants at risk of poor growth and development, management of breastfeeding/lactation difficulties in mothers/caregivers of infants at risk of poor growth and development, supplemental milk for infants at risk of poor growth and development and use of antibiotics for infants at risk of poor growth and development. B. Management of infants and children 6-59 months with wasting and/or nutritional edema This section includes recommendations and good practice statements on admission, referral, transfer and exit criteria for infants and children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, identification of dehydration in infants and children with wasting and/or nutritional edema, rehydration fluids for infants and children with wasting and/or nutritional edema and dehydration but who are not shocked, ready-to-use therapeutic food for treatment of severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, dietary management of infants and children with moderate wasting and vitamin A supplementation in the treatment of children with severe acute malnutrition C. Post-exit interventions after recovery from wasting and/or nutritional edema D. Prevention of wasting and nutritional edema We can summarize the guidelines for management of acute malnutrition in the following: ▪️ Nutritional status must not be seen in isolation. Assessment of an infant’s or child’s health and developmentalstatus (including triage and emergency care) is key for any decision-making for nutritional care and decisionson where this should be delivered. ▪️ Mothers and their infants less than six months at-risk of poor growth and development must be identified earlyand cared for as an inter-dependent unit. Effective and culturally appropriate care—especially for breastfeedingsupport—is vital for their current health as well as one of the most important preventative actions to reducethe prevalence of wasting and/or nutritional edema in later infancy and childhood. ▪️ Not all children with moderate wasting need a specially formulated food to supplement their diet. All childrenwith moderate wasting need a health assessment to rule out medical problems that could be the cause or maindriver of the moderate wasting. They also need access to a nutrient-dense home diet to meet their energeticand nutrient needs. ▪️ Some children with moderate wasting are at greater risk of mortality and non-recovery than others. These riskfactors are related to whether they live in a high-risk context (such as humanitarian crises) as well as specificindividual or social factors. These factors can be used to consider which children should be prioritized overothers to receive specially formulated foods (SFFs) which can be ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), ready to use supplementary food (RUSF) or an improved fortified blended food to supplement their home diet. ▪️ Children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should receive nutritional treatment with an RUTFthat meets the Codex specification. The amount given can be either constant until anthropometric recovery orreduced if it is safe and appropriate to do so. ▪️ Community Health Workers can manage children 6-59 months of age with wasting and/or nutritional edema inthe community as long as they are adequately trained and receive ongoing supervision and support.This includes nutritional supplementation or treatment and medical care as appropriate to the context. |

- Introduction

Undernourished children have weakened immunity and impaired cognitive function, which leads to their poor health outcomes, loss of future productivity, and low academic performance, [1] extrahealthcare expenditures and opportunity costs related to the care of sick children [2]. Consequently, under- nutrition is responsible for almost half (45%) of all deaths in under 5 children worldwide. Annually, 8 million deaths are anticipated to be caused by wasting, with severe wasting responsible for 60% of these deaths in low‐ and middle‐income countries [3].

According to the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates, 45 million infants and children under 5 experienced wasting in 2022; an estimated 13.7 million infants and children under 5 had severe wasting and the remainder had moderate wasting [4]. The risk of wasting and nutritional edema in infants and children, particularly in high-risk contexts where health and socioeconomic indicators are at their poorest [5].

The Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey of (EDHS) 2014 revealed the prevalence of wasting among under-5 children to be 8.4% (up from the reported 7.2% in the 2008 DHS) with 3.8% having severe wasting [6]. Despite that the national prevalence of wasting in under 5 children is 3% in 2021, there is higher prevalence in some Egyptian governorates, as South Sinai 15.9%, Aswan 14.1%, Suez 10.7%, Luxor 8.8%, Qalioubiya 6.8%, Cairo 5.4%, Giza 4.8% and Assuit 4.5% [7].

During the early years of life nutrition is fundamental for child health and development [8]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding initiation within an hour of birth, exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and breastfeeding continuation thereafter [9]. Egypt’s 2014 Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) reported that 27% of mothers-initiated breastfeeding early (IBF) during the first hour after delivery and that only 13% were exclusively breastfeeding their child (EBF) until the age of four or five months, which is almost a 50% decline from the 2008 rates [6].Breastfeeding difficulties are of the main cofactors for the high prevalence of malnutrition.Egypt Family Health Survey 2021 reported that IBF during the first hour after delivery rise a little to 32.8% and 20.7% exclusive breastfeeding for 4-5 months of age [7].This is simple practical guideline for healthcare professionals to manage the emergency situation of refugees that are crossing from different borders of the country.

Identification of acutely malnourished children is thus a priority for timely treatment and ultimately to avoid child illness and death.

This guideline is intended to help and improve the health situation in Egypt in a trial to cope with the global goal to reduce wasting prevalence in high prevalence governorates to 5% by 2025 and 3% by 2030 [10,11]

➡️Purpose&Scope

These guidelines have been developed to standardize the delivery of services and to implement the guidance on the prevention, diagnosis and management of wasting and nutritional edema in infants and children less than 5 years. It provides guidance to primary health care providers, pediatricians and specially trained nurses.

The guidelines aimed to improve early case detection and referral, case management of mild, moderate and severe malnutrition. As a sequence,there will bean improvementin the physical & mental health which is usually reflected on scholastic performance & productivity with decrease the health care cost.

This version of the guideline includes recommendations and good practice statements for infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development (within which infants with wasting and/or nutritional edema are a subset); moderate and severe wasting in infants and children 6-59 months of age and prevention of wasting.

▪️ Management of infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development

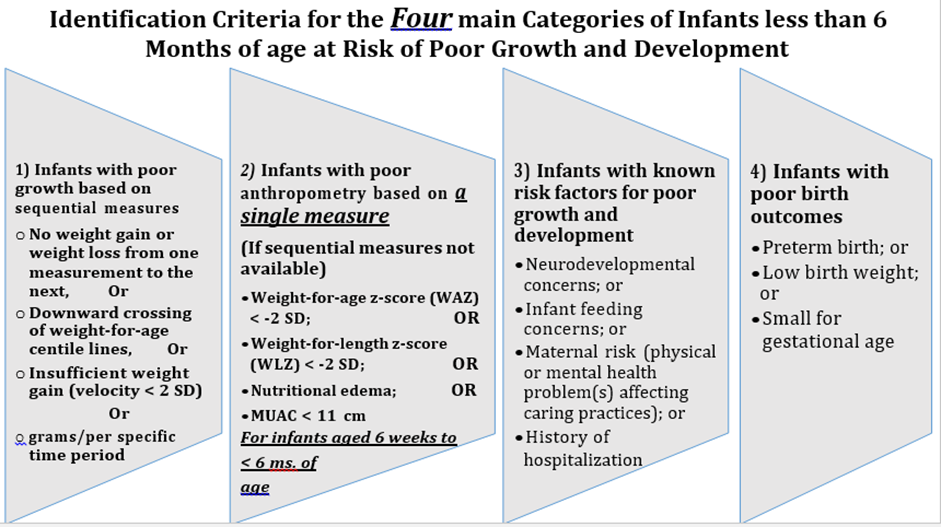

Infants at risk of poor growth and development should include infants less than 6 months of age in any of the following categories with any of the following criteria:

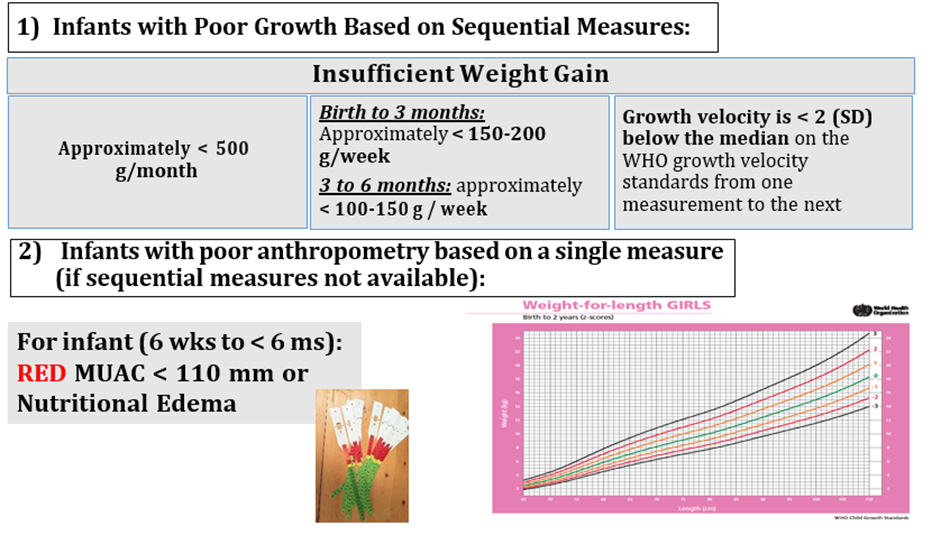

✔️ Infants with poor growth based on sequential measures

• No weight gain or weight loss from one measurement to the next; or

• Downward crossing of weight-for-age centile lines; or

• Insufficient weight gain (velocity standards or grams/per specific time period).

✔️ Infants with poor anthropometry based on a single measure (if sequential measures not available)

• Weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) < -2 SD; or

• Weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) < -2 SD; or

• Nutritional edema; or

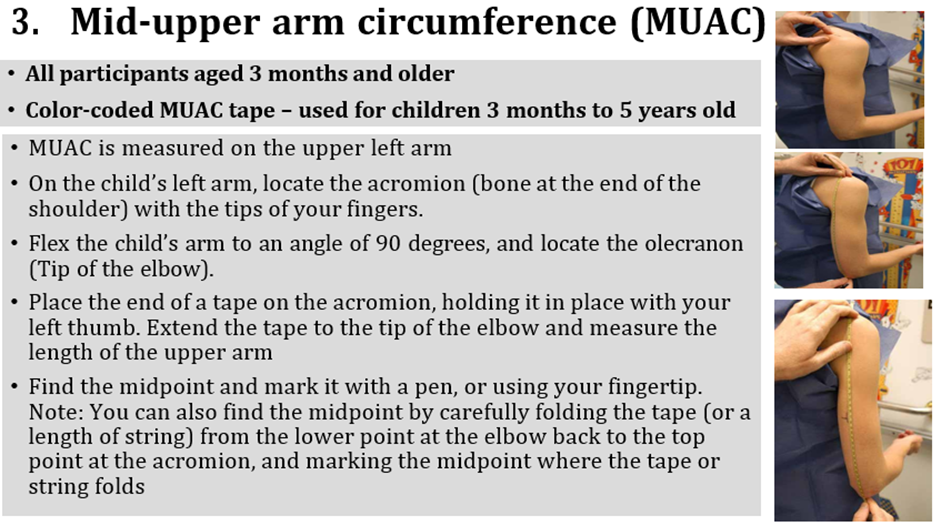

• Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) < 110 mm for infants between 6 weeks to less than 6 months of age.

✔️ Infants with known risk factors for poor growth and development

• Neurodevelopmental concerns; or

• Infant feeding concerns; or

• Maternal risk (physical or mental health problem(s) affecting caring practices); or

• History of hospitalization.

✔️ Infants at risk due to poor birth outcomes

• Preterm birth; or

• Low birth weight; or

• Small for gestational age.

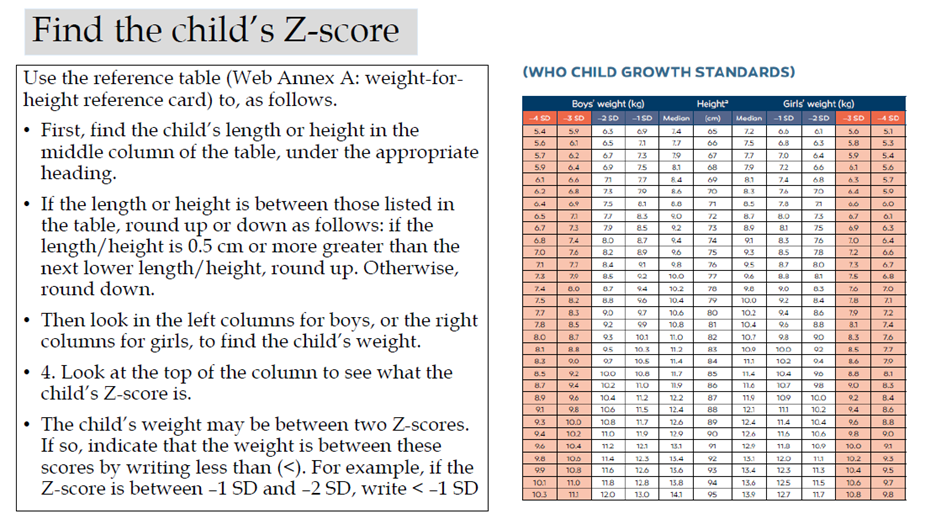

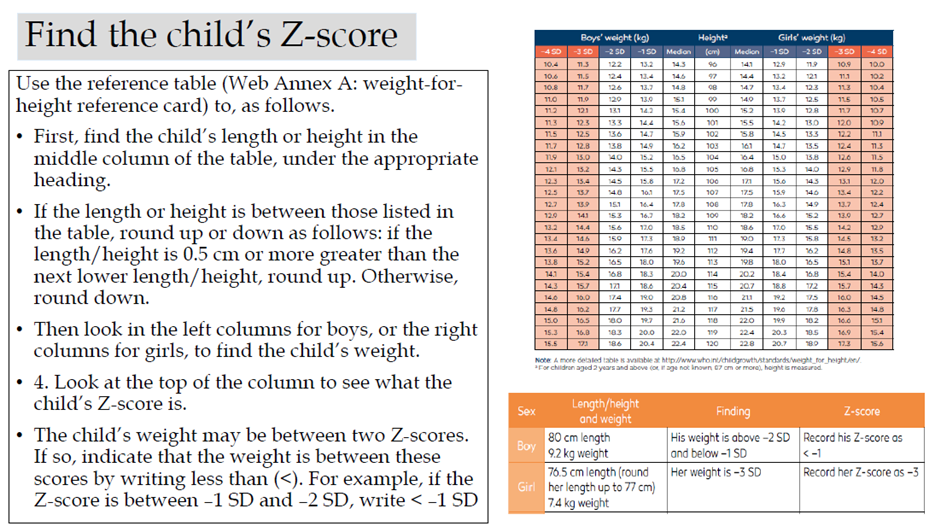

Acute malnutrition in children under 5 years of age is defined in this guideline as having a weight-for-height or weight-for-length z-score more than 2 SD below the median of the WHO child growth standards (WHZ or WLZ < -2) or having nutritional edema. A MUAC less than 125mm can be used as an alternative measure to define acute malnutrition alongside weight-for-height and nutritional edema.

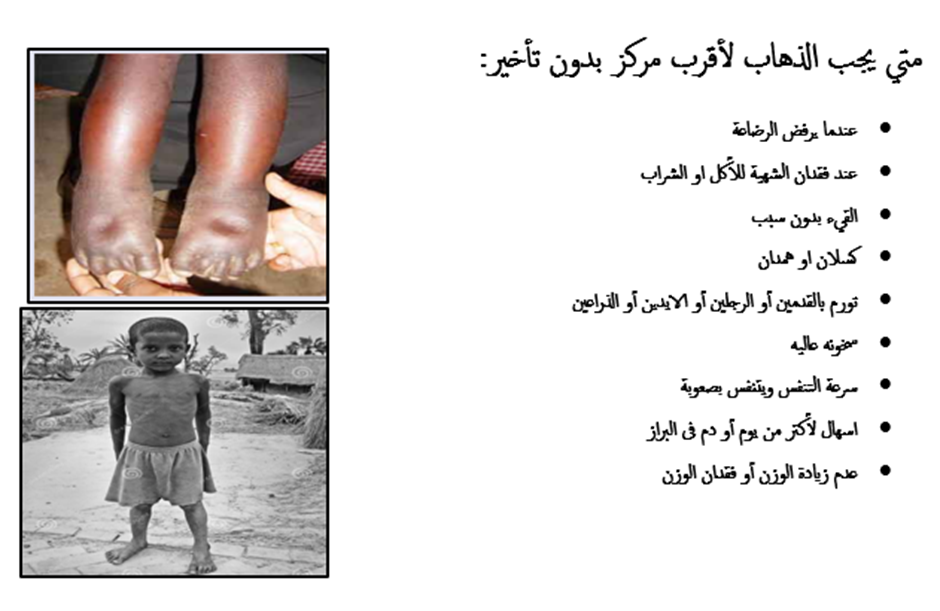

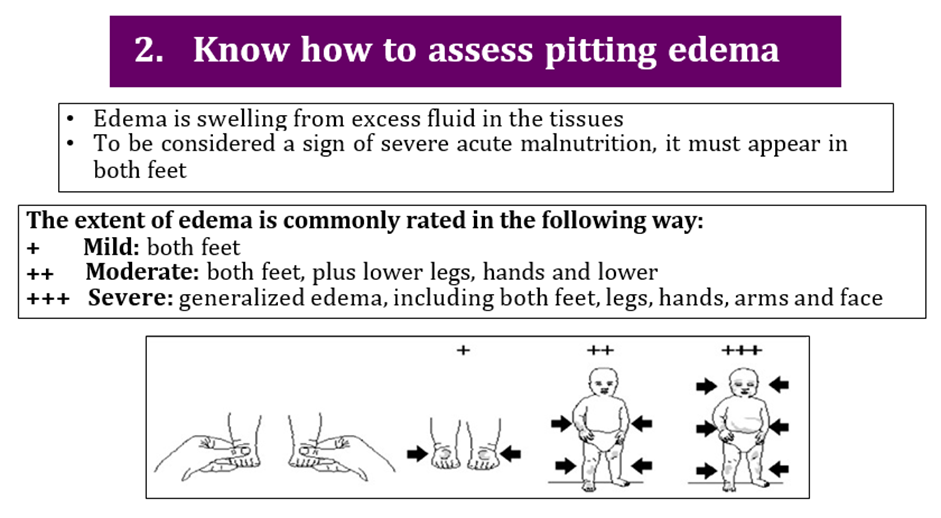

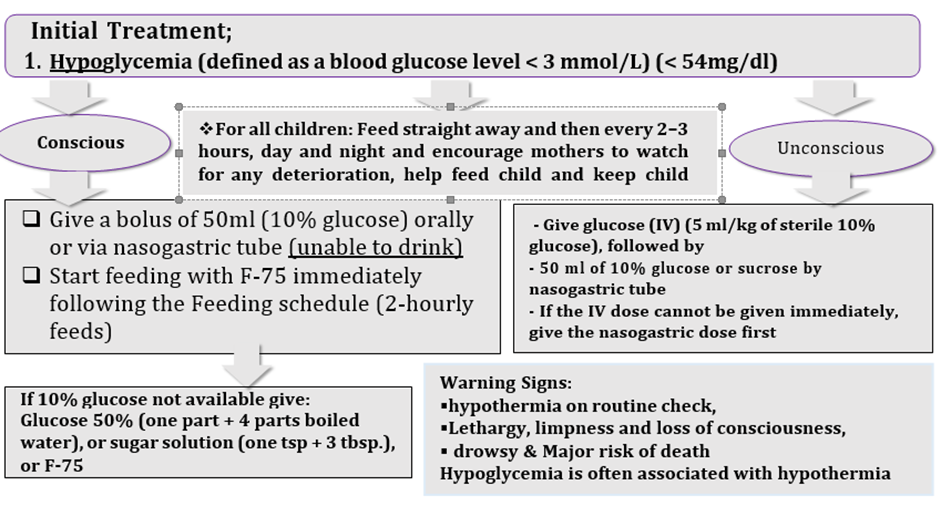

Nutritional edema is bilateral pitting edema which starts in the feet and can progress up to the legs and the rest of the body, including the face. It is pathognomonicof severe acute malnutrition. Clinical assessments for undernutrition should include an assessment for nutritional edema. Acute malnutrition may be further sub-classified to:

• Moderate wasting in infants and children 6-59 months of age

Weight-for-height or weight-length z-score greater than or equal to 3 and less than 2 SD below the WHO child growth standards median (WHZ or WLZ ≥-3 and <-2 SD) (or MUAC ≥115mm to <125mm as an alternative field measure).

• Severe wasting and nutritional edema in infants and children 6-59 months of age

Weight-for-height or weight-for-length z-score greater than 3 SD below the WHO child growth standards median (WHZ or WLZ <-3 SD) (or mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) <115mm as an alternative field measure) and/or nutritional edema.

• Prevention of wasting and nutritional edema

It includes recommendation and good practice statements about individual and community approaches for prevention of wasting and nutritional edema. These approaches may differ greatly by setting, context, and other factors.

- Methods

Methods of search:

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines toconsider for adaptation. Using keywords: Management, nutritional edema, wasting, and children under 5 years.

Inclusion / exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

• Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature

searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

• Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

• Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2013 and later)

• Selecting peer reviewed publications only

• Selecting guidelines written in English language

• Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization to be valid andcomprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input.

• Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thoroughliterature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of therecommendations.

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. The panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 60% on the rigor dimension was retained)

After reviewing all the previous criteria the GDG & methodologists recommended using 2 guidelines:

1- WHO guideline updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children

(2013)

2- WHO guideline on the prevention and management of wasting and nutritional edema (acute

malnutrition) in infants and children under 5 years (2023)

We did Adolopment for these guidelines: (Adoption, Adaptation, and Development)

- Adoption for most of the guideline recommendations.

- Adaptation for 2 recommendation according to GRADE criteria to be suitable to our Economic implications (Evidence to Decision (EtD) table was done)

- Development of Good Practice Statement

Contributors to the guideline development process:

Guideline Development Group (GDG):

The GDG for the guideline on prevention and management of wasting and nutritional oedema (acute

malnutrition) included experts with a range of technical skills and diverse perspectives in the field of clinical nutrition.

The main functions of the GDG were adolopment of WHO guidelines for wasting and undernutrition (2013& 2023), determining the scope of the guideline and guideline, reviewing the evidence, and formulatingevidence-informed recommendations in case of changing strength of recommendations.

Guideline Methodologists:

There were 6 guideline methodologists with expertise in guidelines development, GRADE and translationof evidence into recommendations. Methodologists provided orientation and overview of evidence-informed guideline development processes using the GRADE approach & also, provided AGREE IIassessment of the source guidelines in conjunction with CDG..

External Review Group:

The External Review Group for this guideline comprises 3 clinical experts who have interest and

expertise in the prevention and treatment of wasting and/or nutritional oedema in infants and children as well as representative of WHO and UNICEF Organizations.They were identified by Egyptian Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (EPG) as people whocan provide valuable insights during the guideline development process.

The External Review Group was asked to comment on (peer review) the final guideline to identify any criticism on the content and to comment on clarity and applicability as well as issues relating to implementation, dissemination,ethics, regulations, or monitoring, but not to change the recommendations formulated by the GDG. Themembers of the External Review Group were required to submit declarations of interest before the peerreview process.

Guideline Development Group meetings:

GDG meetings were organized virtually twice weekly. Due to the extensive scope of

the guideline, EPG Chair was responsible for the timetable and objectives of each meeting. GDG meetingswere also attended by members of the methodologists and systematic. Working rules for each contributor type were outlined by the chair at the start of eachmeeting, covering aspects such as vocal rights, voting, and evidence to decision and recommendationformulating processes.

Declarations of interests:

Prospective members of the GDG were asked to fill in and sign the standard WHO declaration of interestand confidentiality undertaking forms. All guideline members and methodologists were also asked to fillin and sign the standard WHO declaration-of-interests.

Members of the external review group will be asked to fill in and sign the standard WHO declaration-

of-interests form before the peer review process.

Evidence for the guideline:

We used the GRADE system (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assigning the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations that includes the following definitions [13]. Informed by the evidence required for the GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) table was done while considering changingstrength of recommendations according to availability of some resources in the recommendations (we didthis for only 2 recommendations).

Description of the interpretation of the GRADE four levels of certainty of evidence:

Table 1. Classification of the Quality of Evidence

|

High |

We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

|

Moderate |

We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

|

Low |

Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

|

Very Low |

We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

GRADE EtD criteria and considerations that link to the strength of recommendations:

Criteria Considerations:

Benefits and harms: When a new recommendation is developed, desirable effects (benefits) need to be weighedagainst undesirable effects (risks/harms), considering any previous recommendation or

another alternative. The larger the gap or gradient in favor of the desirable effects over the

undesirable effects, the more likely that a strong recommendation will be made.

Certainty of theevidence about the effects: The higher the certainty of the scientific evidence base, the more likely that a strong will be made.

Values andpreferences: If there is no important uncertainty or variability in how much people value the mainoutcomes, it is likely that a strong recommendation will be made. Uncertainty or variability

around these values that could likely lead to different decisions, is more likely to lead to a

conditional recommendation.

Economicimplications: Lower costs (monetary, infrastructure, equipment or human resources) or greater cost-effectiveness are more likely to support a strong recommendation.

Equity and humanrights: If an intervention will reduce inequities, improve equity or contribute to the realization ofhuman rights, the greater the likelihood of a strong recommendation.

Feasibility: The greater the feasibility of an intervention to all stakeholders, the greater the likelihood ofa strong recommendation.

Acceptability: If a recommendation is widely supported by health workers and program managers andthere is widespread acceptance for implementation within the health service, the likelihood

of a strong recommendation is greater.

Table 2. Classification of the Strengths of Recommendations

|

Strong |

The desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects (or vice versa), so most patients should receive the recommended course of action. |

|

|

There is uncertainty about the trade-offs. The clinician and patient need to discuss the patient's values and preferences, and the decision should be individualized. |

Developing good practice statements:

The GDG also developed good practice statements for this guideline, which are actionable messages relevant to theguideline questions. The justification for each good practice statement was carefully considered by the GDG with anemphasis that they are clearly needed. Good practice statements were developed, guided by the following GRADEcriteria:

1- Message is really necessary with regard to actual healthcare practice

2- Have large net positive consequence (relevant outcomes and downstream consequences) (GRADE EtDdomains)

3- Collecting and summarizing the evidence is a poor use of time and resources

4- Include a well-documented, clear rationale connecting indirect evidence

5- Are clear and actionable statements.

The GDG collectively drafted and finalized good practice statements with relevant justifications and remarks to helpwith their interpretation, with close support and input from the consultant and guideline methodologists.

- Recommendations

|

Table 3. Recommendations |

|||

|

A. Management of infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development |

|||

|

N |

Health questions |

Source Guideline |

Recommendations (Quality of evidence, Strength of Recommendation) |

|

A1 |

Interventions for mothers/caregivers of infants at risk of poor growth and development In mothers/caregivers of infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, What interventions can guarantee the best health outcome for both of them? |

GDG |

Good practice statement A1. Mother/caregiver and infant should be considered as inter- dependent pair. They should receive regular care and monitoring by health professionals in the form of: 1. Medical and anthropometric assessment for Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development to a. Achieve early detection of any acute medical problems and appropriate intervention, and b. Enable these infants to grow and develop in a healthy way 2. Maternal/caregiver Comprehensive assessment and support are recommended to ensure maternal/caregiver physical and mental health and well-being |

|

Admission, referral, transfer, and exit criteria for infants at risk of poor growth and development.

|

|||

|

A2 |

a) In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for referral to treatment in an inpatient setting?

b) In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for an in-depth assessment to consider if they need inpatient admission or outpatient management?

c) In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, what are the criteria that best inform the decision to initiate treatment in an outpatient/community setting?

|

WHO 2023 |

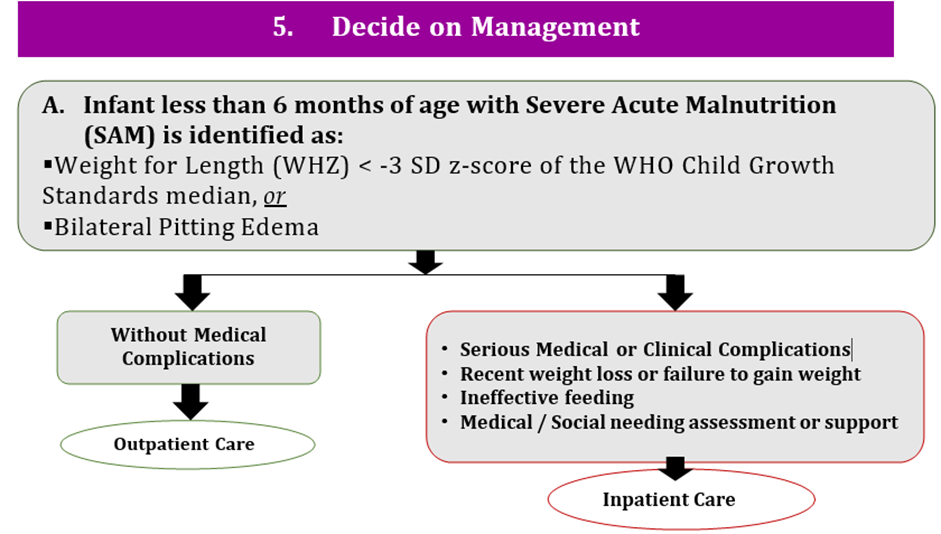

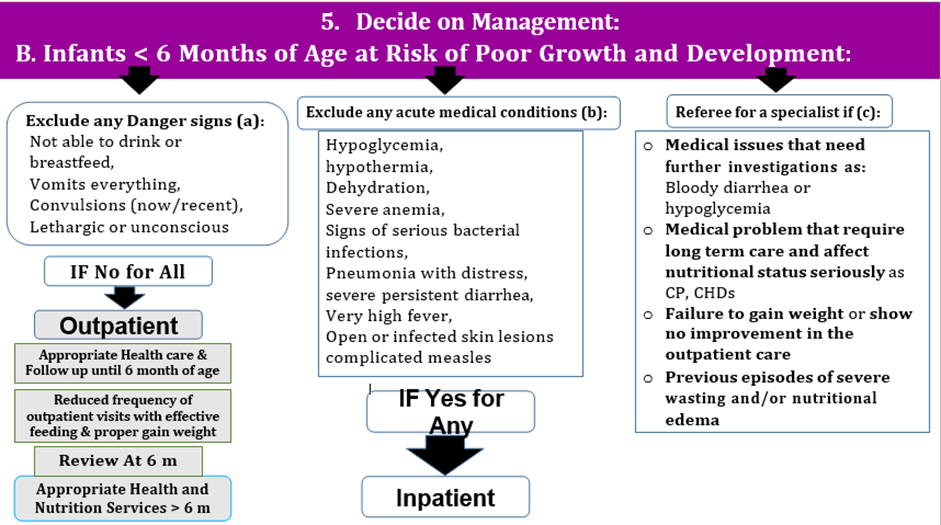

Conditional recommendation, Low certainty evidence A2. a) Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development who have any of the following characteristics should be referred and admitted for inpatient care: i. one or more Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) danger signs** ii. acute medical problems or conditions under severe classification as per IMCI*** iii. edema (nutritional) iv. recent weight loss. b) Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development who do not meet any of the criteria from part a should have an in-depth assessment to consider if they need inpatient admission or outpatient management based on clinical judgement if they have any of the following characteristics:****

c) Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development who have all the following characteristics should be enrolled and managed as outpatients: i. no danger signs or/ any of the criteria from (part a) needing inpatient admission. ii. no criteria needing in-depth assessment (part b) or when criteria from part b are present but an in-depth assessment has been completed and determined that no inpatient admission is needed (Feeding problems that can be managed in outpatient care, diarrhea with no dehydration, respiratory infections with no signs of respiratory distress, malaria with no signs of severity) |

|

A3 |

In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development admitted for inpatient treatment, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for transfer to outpatient/community treatment?

|

WHO 2023 |

Strong recommendation for, Moderate certainty evidence A3. Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development who are admitted for inpatient care can be transferred to outpatient care when:

|

|

A4 |

In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development receiving outpatient/community treatment, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for exit from outpatient/community treatment? |

WHO 2023 |

Conditional recommendation for, Very low certainty evidence A4. a) Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development can have a reduced frequency of outpatient visits when they: i. are breastfeeding effectively or feeding well with replacement feeds, and ii. have sustained weight gain# for at least 2 consecutive weekly visits. b) Infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development should be assessed (including assessment of their anthropometry) once they reach 6 months of age to determine if they need i. An ongoing follow-up or ii. A referral to services for infants 6 months of age and older (including nutritional treatment/supplementation) as appropriate according to their clinical and nutritional status## |

|

A5 |

Management of breastfeeding/lactation difficulties in

mothers/caregivers of infants at risk of poor growth and development |

WHO 2023 |

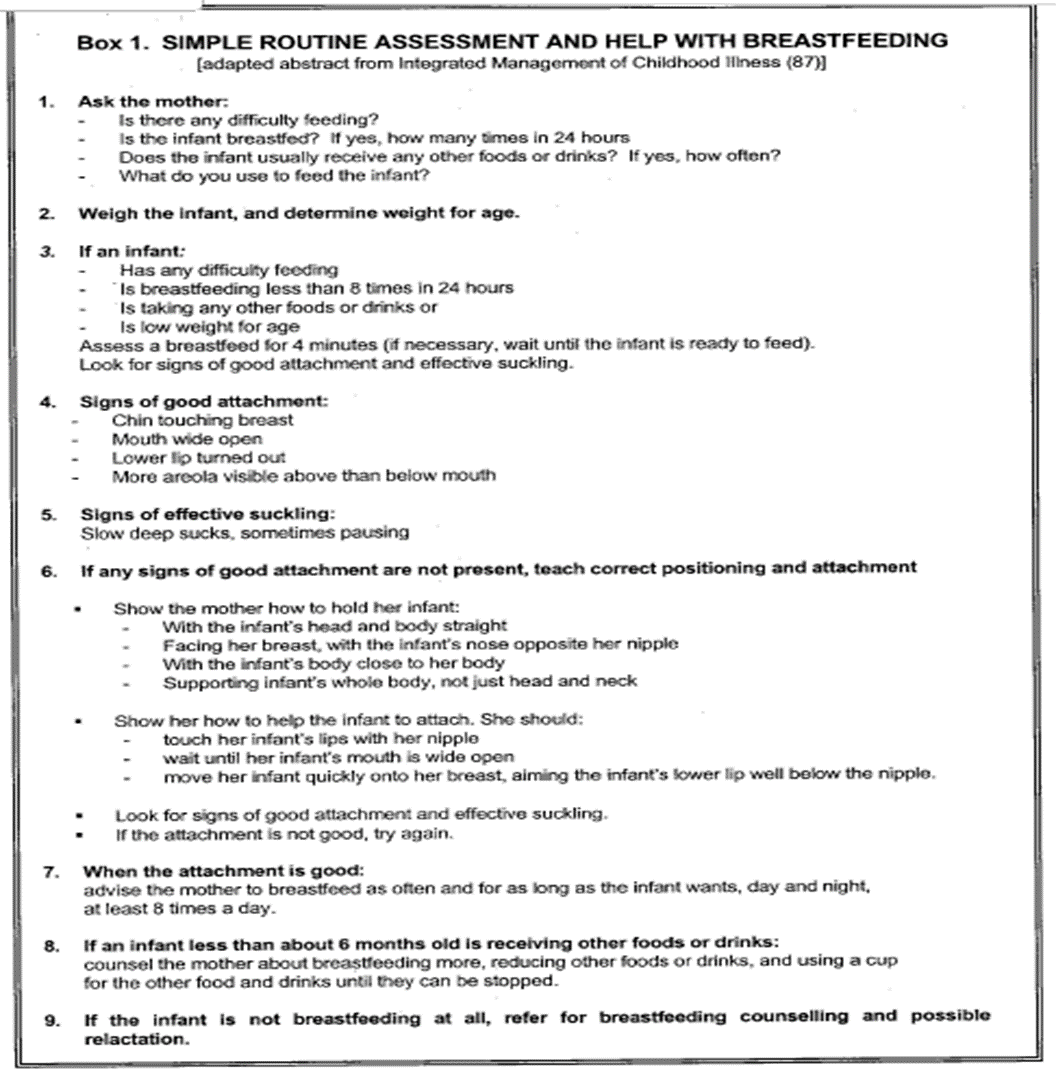

Good practice statement A5. For infants less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development, health care providers should conduct comprehensive assessments of the mother/caregiver-infant pair and follow best practices for the management of breastfeeding/lactation challengesand underlying factors contributing to these challenges. Preferably by lactation consultant

|

|

A6 |

Supplemental milk for infants at risk of poor growth and development In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, which criteria best determine if an infant should be given a supplemental milk (in addition to breastmilk if the infant is breastfed) and when? |

WHO 2023 |

Good practice statement A6. Decisions about whether an infant less than 6 months of age at risk of poor growth and development needs a supplementary milk in addition to breastfeeding must be based on i. A Comprehensive assessmentof themedical, nutritional/ feeding needs+of the infant as well as, ii. The physical and mental health of the mother/caregiver. This applies to infants who are enrolled in outpatient care or admitted into inpatient care.

|

|

A7 |

In infants less than 6 months of age with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, what is the most effective supplemental milk (donor human milk, human milk from wet nurse, commercial infant formula, F-75, F-100, or diluted F-100) and for how long should these be given? |

WHO 2023 |

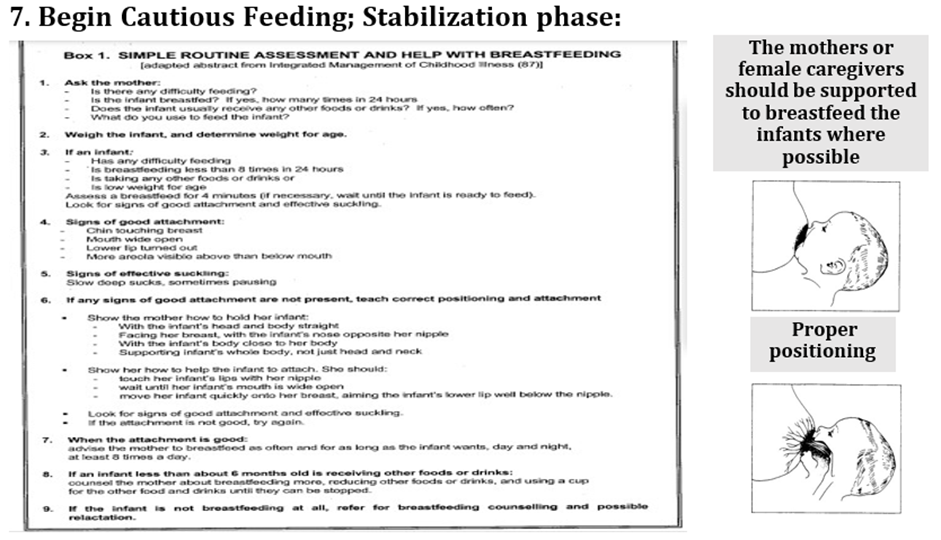

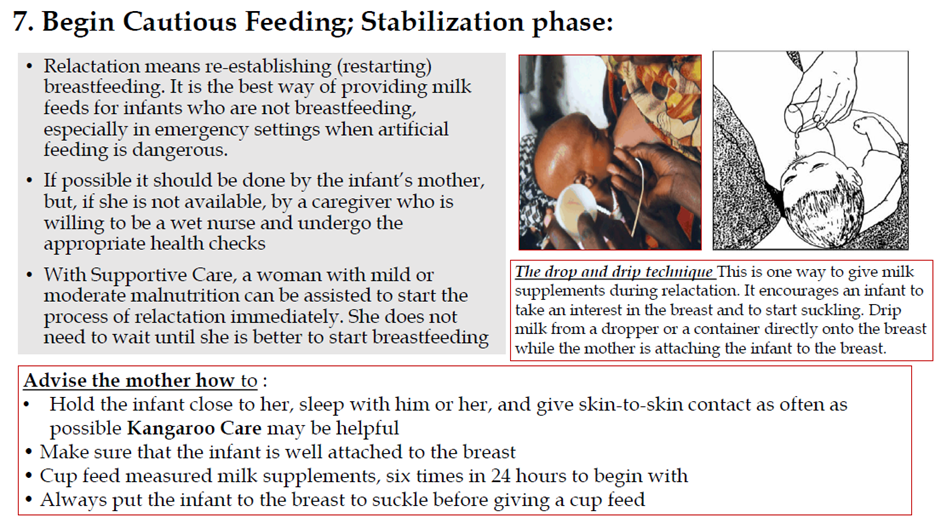

Strong recommendation for, very low certainty evidence A7. Infants who are less than 6 months of age with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who are admitted for inpatient care: a) should be breastfed where possible and the mothers or female caregivers should be supported to breastfeed the infants. If an infant is not breastfed, support should be given to the mother or female caregiver to re-lactate. If this is not possible, wet nursing should be encouraged. b) should also be provided a supplementary feed: - supplementary suckling approaches should, where feasible, be prioritized. - for infants with severe wasting but no edema, expressed breast milk should be given, and, where this is not possible, commercial (generic) infant formula or F-75 or diluted F-100++may be given, either alone or as the supplementary feed together with breast milk. - for infants with edema, commercial (generic) infant formula or F-75 should be given as a supplement to breast milk. -c) should not be given full-strength F-100++if they are clinically unstable less 6 month and/or have diarrhea or dehydration and/or nutritional edema -d) should, if there is no realistic prospect of being breastfed, be given appropriate and adequate replacement feeds such as commercial (generic) infant formula, with relevant support to enable safe preparation and use, including at home when transferred from inpatient care. |

|

A8 |

Antibiotics for infants at risk of poor growth and development In infants less than 6 months at risk of poor growth and development, should an antibiotic be routinely given? |

WHO 2013 |

Strong recommendation against, Low certainty evidence A8. Children who are undernourished but who do not have severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should not routinely receive antibiotics unless they show signs of clinical infection.

|

Remarks on recommendations

**IMCI danger signs include not able to drink or breastfeed; vomits everything; had convulsions recently; lethargic or unconscious; convulsing now.

*** Acute medical problems (as per IMCI classification) which need referral to inpatient care include signs of possible serious bacterial infection in infants less than 2 months of age

a. Shock

B. Oxygen saturation <90%

C. Pneumonia (with chest indrawing; and/or fast breathing; and if possible to measure, oxygen saturation <94%)

D. Dehydration (including some or severe dehydration)

E. Severe persistent diarrhoea (diarrhoea for 14 days or more plus dehydration)

F. Very severe febrile illness – in a malaria zone or with a positive rapid diagnostic test (rdt), this is treated as severe malaria.

G. Very severe febrile illness – where there is no risk of malaria or with a negative rdt, this is treated as bacterial disease, e.g. Meningitis, etc.

H. Severe complicated measles

I. Mastoiditis

J. Severe anemia (severe palmar pallor or as per age-associated hemoglobin levels)

K. Severe side effects from antiretroviral therapy (for hiv) – skin rash, difficulty breathing and severe abdominal pain, yellow eyes, fever, vomiting.

L. Open or infected skin lesions associated with nutritional edema.

M. Other stand-alone ‘priority clinical signs’ not classified as dangers signs: hypothermia (<35°C axillary or 35.5°C rectal) or high fever (≥38.5°C axillary or 39°C rectal)

**** In depth assessment and clinical judgment of qualified physicians

#sustained weight gain: approximately more than 150-200 g/week in birth to 3 months, and 3 to 6 months approximately less than 100-150 g / week

## An infant at 6 months of age or older who meets anthropometric and clinical criteria of moderate wasting or severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should be referred to the appropriate services for medical management (if needed), health and nutrition education and counselling, nutritional supplementation (if appropriate) or nutritional treatment.

Other ongoing follow-up or referral for this group of infants could be routine vaccination services, regular infant and young child feeding services, breastfeeding support, specialized medical services for congenital diseases or disabilities, outpatient management of HIV or tuberculosis, psychological support for the mother/caregiver, social protection services, etc.

+Feeding assessments should include the following domains: infant and mother/caregiver health status (including assessing for disabilities), maternal responsiveness to infant cues, for breastfeeding specifically: positioning, latching, sucking, and swallowing (noting that these aspects will vary with the age of the infant).

++Full strength F100 is therapeutic milk with renal solute load and risk of hyponatremic dehydration.

|

Table 4. Recommendations |

|||

|

B. Management of infants and children 6-59 months with wasting and/or nutritional edema |

|||

|

N |

Health questions |

Source Guideline |

Recommendations (Quality of evidence, Strength of Recommendation) |

|

B1 |

Admission, referral, transfer and exit criteria for infants and children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema. B1. In emergency health setting how to pick up infants and children 6-59 months old with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema |

GDG |

Good practice statement B1. Identification of nutritional status should be a vital component of initial assessment to pick up infants and children 6-59 months old with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema with emergency or danger signs receive immediate intervention. Others receive appropriate care as per their clinical status and classification |

|

B2 |

a) In infants and children 6-59 months with wasting and/or nutritional edema, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for referral to treatment in an inpatient setting for wasting and/or nutritional edema?

b) In infants and children 6-59 months, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for in depth assessment?

c) In infants and children 6-59 months, what are the criteria that best inform the decision to initiate treatment in an outpatient/ community setting for wasting and/or nutritional edema?

|

WHO 2023 |

Conditional recommendation for, Low certainty evidence B2. a) Infants and children 6-59 months old with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who have any of the following characteristics should be referred and admitted for inpatient care: i. One or more Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) danger signs ii. Acute medical problems iii. Severe nutritional edema (+++) iv. Poor appetite (failed the appetite test). b) Infants and children 6-59 months old with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who do not meet any of the criteria from part a but who do have any of the following characteristics are likely to benefit from an in-depth assessment to inform the decision on possible referral to inpatient: * i. Medical problems that do not need immediate inpatient care, but do need further examination and investigation (e.g. bloody diarrhea, hypoglycemia, HIV-related complications); ii. Medical problems needing mid or long-term follow-up care and with a significant association with nutritional status (e.g. congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy or other disability, HIV, tuberculosis). iii. Failure to gain weight or improve clinically in outpatient care. iv. Previous episode(s) of severe wasting and/or nutritional edema. c) Infants and children 6-59 months old with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who have all the following characteristics should be enrolled and managed as outpatients: i. Good appetite (passed the appetite test); and ii. No danger signs or any of the acute medical problems from part a ii; and iii.No criteria needing in-depth assessment (see part b) or criteria from part b present, but an in-depth assessment has been completed and no inpatient admission needed (e.g. diarrhea with no dehydration, respiratory infections with no signs of respiratory distress, malaria with no signs of severity). |

|

Therapeutic feeding approaches in the management of severe acute malnutrition in children who are 6–59 months of age |

|||

|

B3 |

In infants and children with severe wasting or edema, what is the inpatient therapeutic feeding approaches in management? |

WHO 2013 |

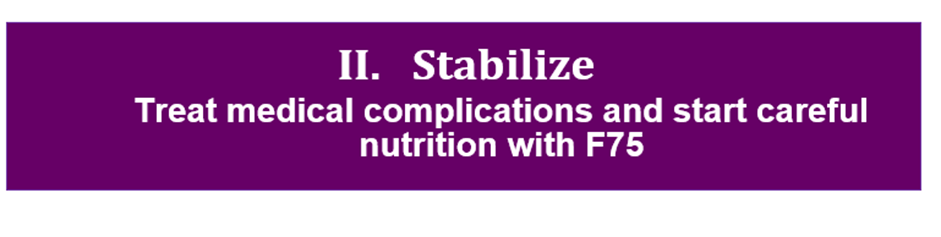

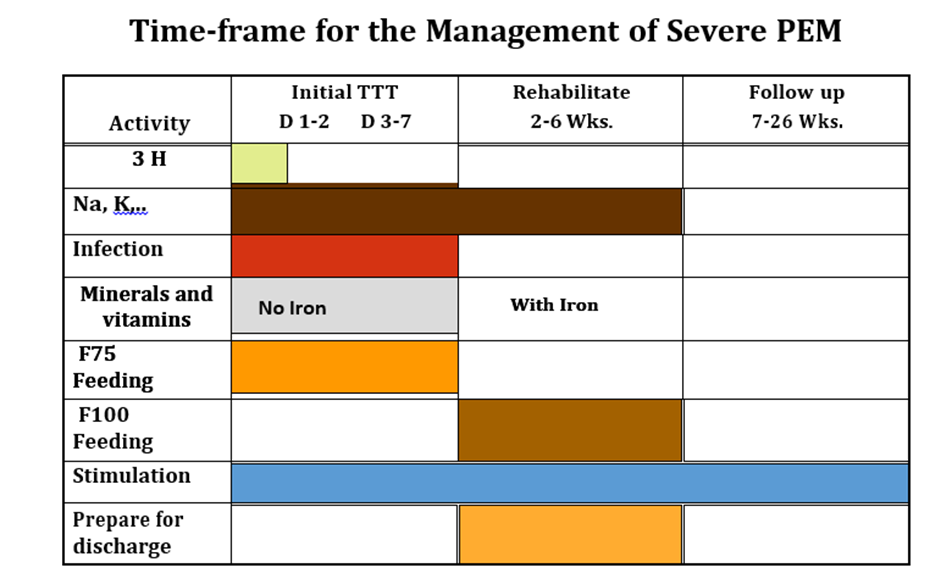

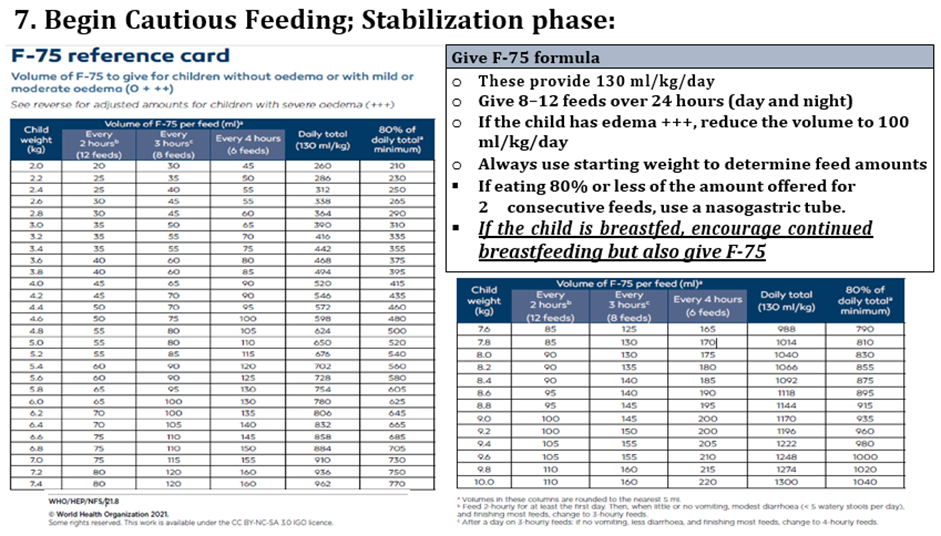

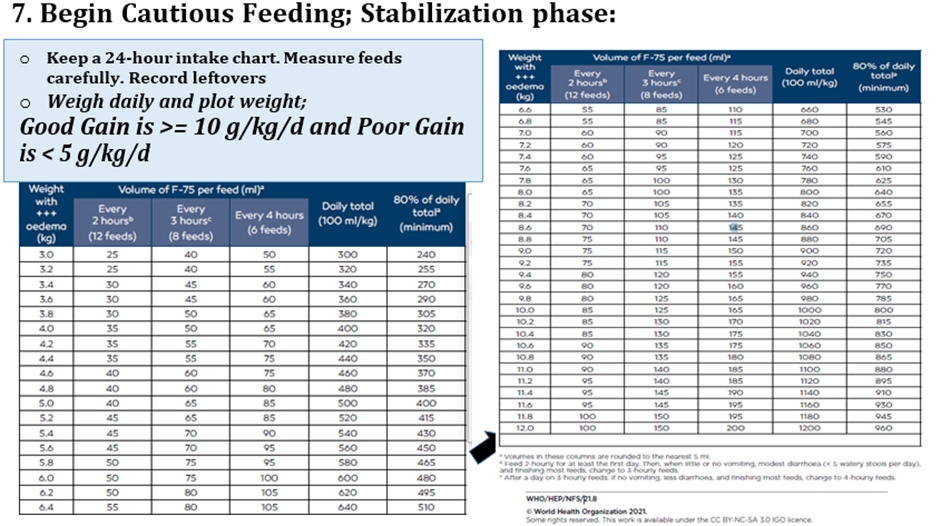

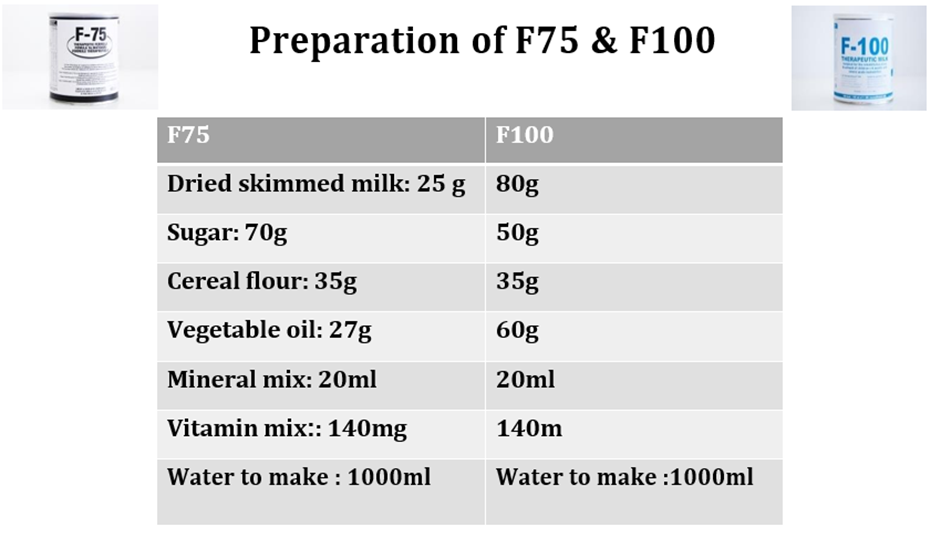

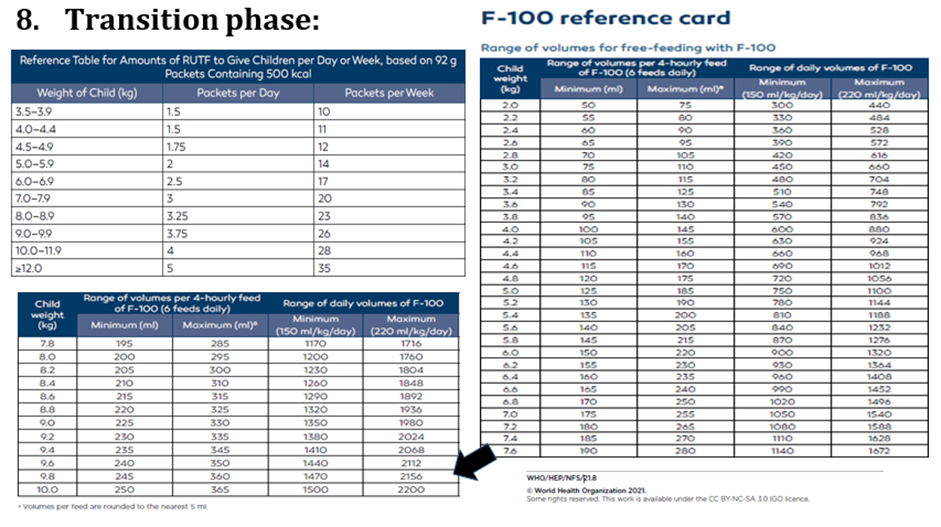

Conditional recommendation, very low-quality evidence B3. In inpatient settings, where ready-to-use therapeutic food is provided as the therapeutic food in the rehabilitation phase (following F-75 in the stabilization phase) Once children are stabilized, have appetite and reduced edema and are therefore ready to move into the rehabilitation phase, they should transition from F-75 to ready-to-use therapeutic food over 2–3 days, as tolerated. The recommended energy intake during this period is 100–135 kcal/kg/day. The optimal approach for achieving this is not known and may depend on the number and skills of staff available to supervise feeding and monitor the children during rehabilitation Two options for transitioning children from F-75 to ready-to use therapeutic food aresuggested: a. start feeding by giving ready-to-use therapeutic food as prescribed for the transition phase. Let the child drink water freely. If the child does not take the prescribed amount of ready-to-use therapeutic food, then top up the feed with F-75. Increase the amount of ready-to-use therapeutic food over 2–3 days until the child takes the full requirement of ready-to-use therapeutic food, or b. Give the child the prescribed amount of ready-to-use therapeutic food for the transition phase. Let the child drink water freely. If the child does not take at least half the prescribed amount of ready-to-use therapeutic food in the first 12 h, then stop giving the ready-to-use therapeutic food and give F-75 again. Retry the same approach after another 1–2 days until the child takes the appropriate amount of ready-to-use therapeutic food to meet energy needs.

|

|

B4 |

In infants and children with complicated severe wasting or edema receiving F100 formula, When to change to ready to use therapeutic food? |

WHO 2013 |

Conditional recommendation, very low-quality evidence B4. In inpatient settings where F-100 is provided as the therapeutic food in the rehabilitation phase Children who have been admitted with complicated severe acute malnutrition and are achieving rapid weight gain on F-100 should be changed to ready-to-use therapeutic food and observed to ensure that they accept the diet before being transferred to an outpatient program. |

|

B5 |

If F100 or F 75 formula are not available, what formula is recommended to use? |

GDG |

Good practice statement B5. If F100 or F 75 formula are not available, other commercial formula could be used to fulfil the recommended caloric and protein requirement |

|

B6 |

In infants and children with severe wasting or edema who are not tolerating F-75 or F-100, which formula can be used? |

GDG |

Good practice statement B6. In infants and children 6-59 months of age with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who are not tolerating standard formula could be shifted to low lactose formulas and assessed for tolerance. |

|

B7 |

Ready-to-use therapeutic food for treatment of severe wasting and/or nutritional edema. In infants and children 6-59 months with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, what is the optimal quantity and duration of RUTF? |

WHO 2023 |

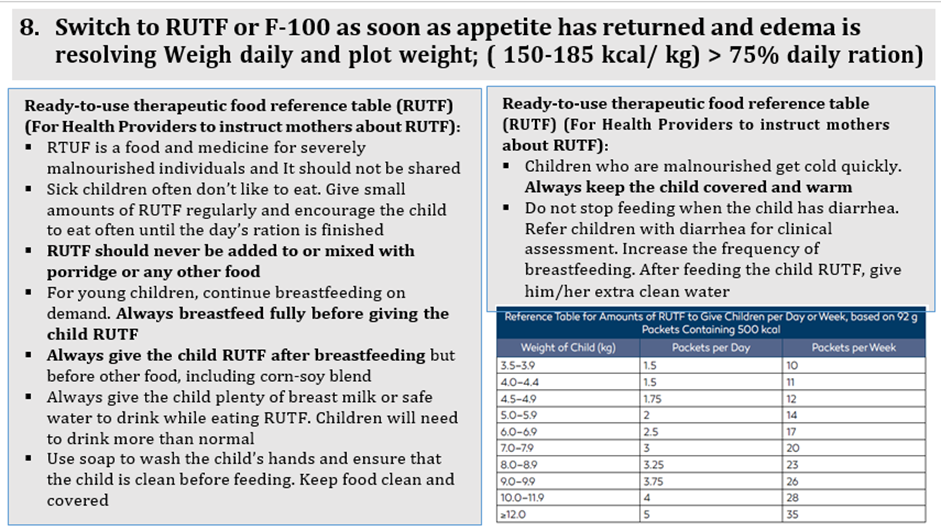

Conditional recommendation, Low certainty evidence B7. In infants and children 6-59 months of age with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who are enrolled in outpatient care, ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) should be given in a quantity that will provide: •150-185 kcal/kg/day until anthropometric recovery and resolution of nutritional edema; or •150-185 kcal/kg/day until the child is no longer severely wasted and does not have nutritional edema, then the quantity can be reduced to provide 100-130 kcal/kg/day, until anthropometric recovery and resolution of nutritional edema |

|

B8 |

In infants and children 6-59 months with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, which formula to use if RUTF is not available? |

GDG |

Good practice statement B8. If RUTF is not available, available standard formula can be used with special consideration to protein and caloric content |

|

B9 |

In infants and children 6-59 months admitted for inpatient treatment of wasting and/or nutritional edema, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for transfer to outpatient/community treatment? |

WHO 2023 |

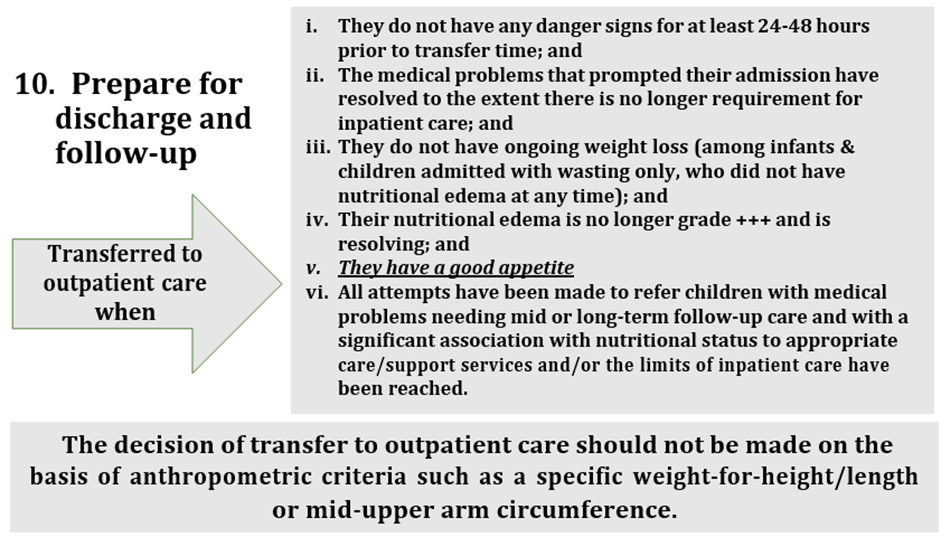

Strong recommendation, for Moderate certainty evidence. B9. a) Infants and children 6-59 months with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who are admitted to inpatient care can be transferred to outpatient care when: i. They do not have any danger signs for at least 24-48 hours prior to transfer time; and ii. The medical problems that prompted their admission have resolved to the extent there is no longer requirement for inpatient care; and iii. They do not have ongoing weight loss (among children admitted with wasting only, who did not have nutritional edema at any time); and iv. Their nutritional edema is no longer grade +++ and is resolving; and v. They have a good appetite. vi. All attempts have been made to refer children with medical problems needing mid or long-term follow-up care and with a significant association with nutritional status to appropriate care/support services and/or the limits of inpatient care have been reached. b) The decision to transfer children from inpatient to outpatient care should not be made based on anthropometric criteria such as a specific weight-for-height/length or mid-upper arm circumference. Instead, the criteria listed above should be used. c) Upon deciding to transfer children from inpatient to outpatient care, caregivers must be linked to appropriate outpatient care with nutrition services. d) Additional social and family factors should be identified and addressed before transfer to outpatient care to ensure that the household has the capacity for care provision |

|

B10 |

In infants and children 6-59 months with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema, what is the necessity of discharge planning? |

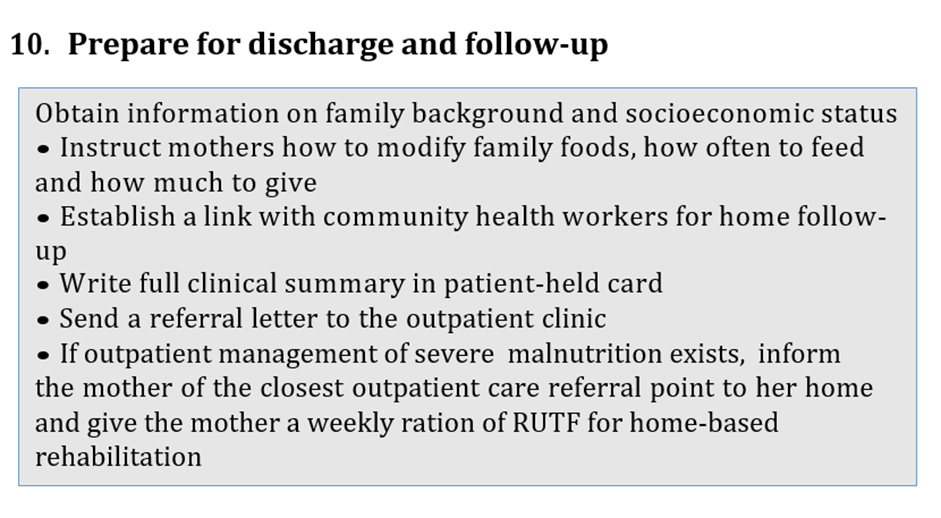

GDG |

Good practice statement B10. Discharge planning that is timely, efficient, and holistic is vital to continuity of care between inpatient and outpatient services. This is to ensure that children are discharged from inpatient care at the appropriate time and with definitive guidance given to caregivers for ongoing nutritional, medical, and psychosocial support services. |

|

B11 |

In infants and children 6-59months receiving outpatient/community treatment for wasting and/or nutritional edema, what are the criteria that best inform the decision for exit from outpatient/community treatment? |

WHO 2023 |

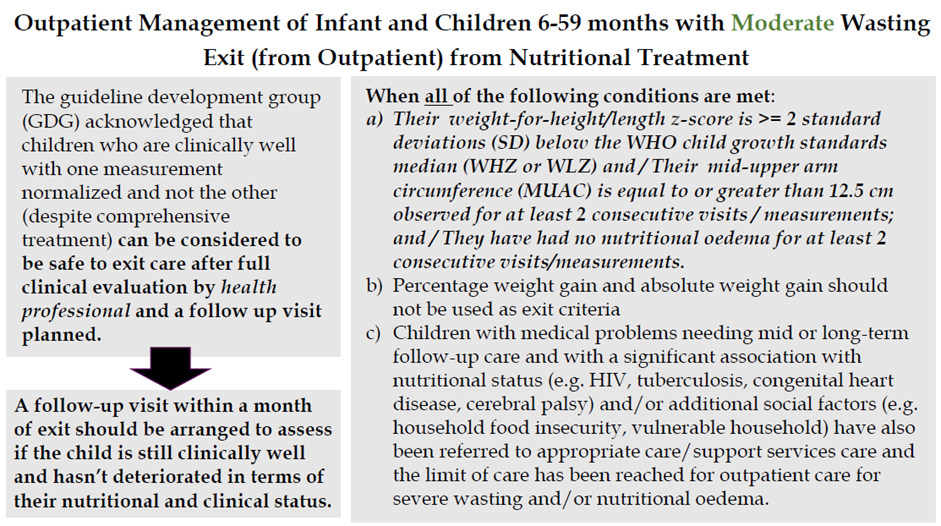

Conditional recommendation, very low certainty evidence B11. a) Infants and children 6-59 months with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should only exit from nutritional treatment when all the following conditions are met: i. Their weight-for-height/length z-score is equal to or greater than 2 standard deviations (SD) below the WHO child growth standards median (WHZ or WLZ ≥ -2) and their mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) is equal to or greater than 125mm observed for at least 2 consecutive visits/measurements; and ii. They have had no nutritional edema for at least 2 consecutive visits/measurements. b) Percentage weight gain and absolute weight gain should not be used as exit criteria. c) Children with medical problems needing mid or long-term follow-up care and with a significant association with nutritional status (e.g. HIV, tuberculosis, congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy) and/or additional social factors (e.g. household food insecurity, vulnerable household) have also been referred to appropriate care/support services care and the limit of care has been reached for outpatient care for severe wasting and/or nutritional edema. |

|

B12 |

Identification of dehydration in infants and children with wasting and/or nutritional edema In infants and children with moderate or severe wasting or edema, how can dehydration be identified? |

GDG |

Good practice statement B12. Accurate classification of hydration** status in children with wasting and/or nutritional edema who have diarrhea or other fluid losses is vital to provide and monitor appropriate treatment and must be frequently reassessed. |

|

B13 |

Rehydration fluids for infants and children with wasting and/or nutritional edema and dehydration but who are not shocked. B12. In infants and children with severe wasting or edema and dehydration but who are not shocked, what is the effective oral rehydration therapy? |

GDG |

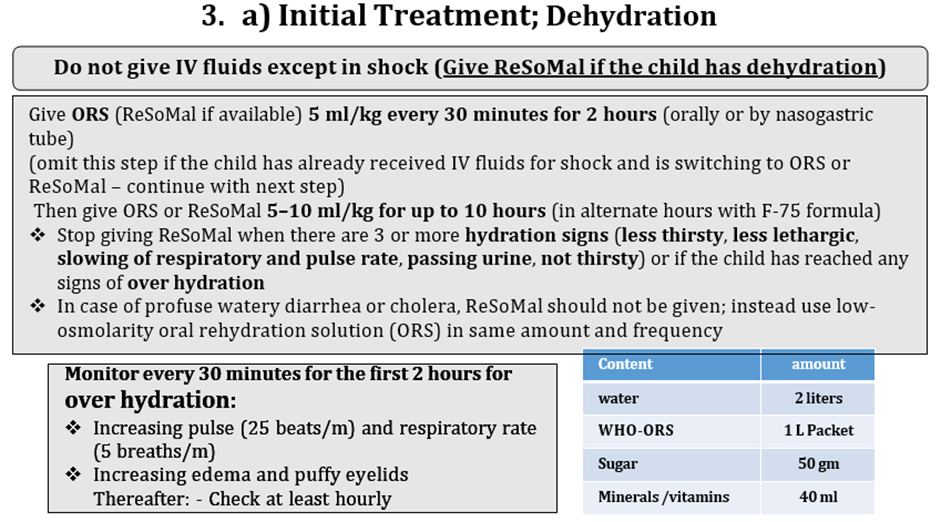

Good practice statement B13. In infants and children 6-59 months of age with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema who are dehydrated but not in shock, low-osmolarity Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) can be used. Rehydration Solution for Malnourished children (ReSoMal) is preferred if available |

|

B14 |

In infants and children with moderate wasting or edema and dehydration but who are not shocked, what is the effective oral rehydration therapy? |

WHO 2023 |

Conditional recommendation, very low certainty evidence B14. In infants and children 6-59 months with moderate wasting who are dehydrated but not in shock, low-osmolarity Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) should be administered in accordance with existing WHO recommendations for all children apart from those with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema. |

|

B15 |

Dietary management of infants and children with moderate wasting In infants and children 6-59 months with moderate wasting, what is the appropriate dietary treatment in terms of optimal type, quantity, and duration?

|

WHO 2023 |

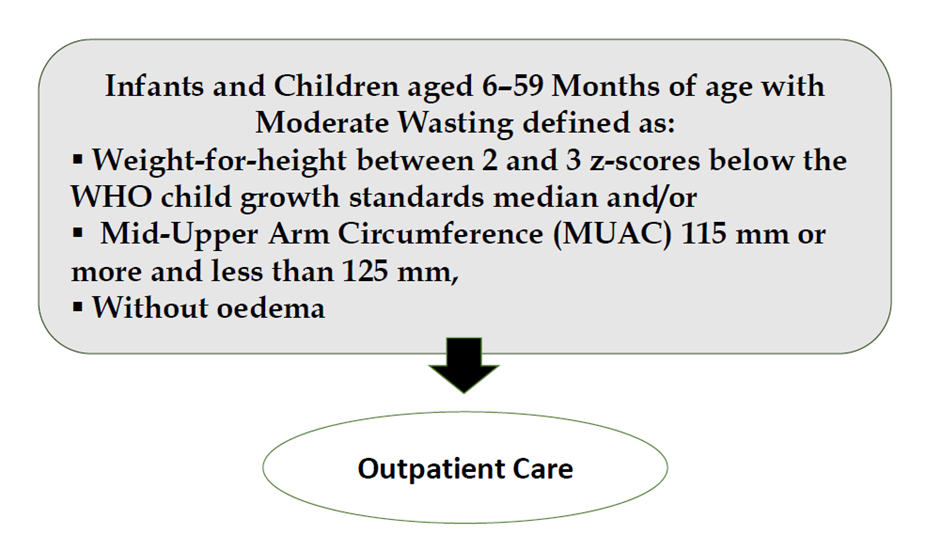

Good practice statement B15. Infants and children aged 6–59 months of age with moderate wasting (defined as a weight-for-height between 2 and 3 z-scores below the WHO child growth standards median and/or a mid-upper arm circumference 115 mm or more and less than 125 mm, without edema) should have access to a nutrient-dense food fully meet their extra needs for recovery of weight and height and for improved survival, health, and development. |

|

B16 |

In infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting what they should be assessed for? |

WHO 2023 |

Good practice statement B16. All infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting should be assessed comprehensively and treated wherever possible for medical and psychosocial problems leading to or exacerbating this episode of wasting.

|

|

B17 |

In infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting when they should be considered for specially formulated food with councelling? |

WHO 2023 |

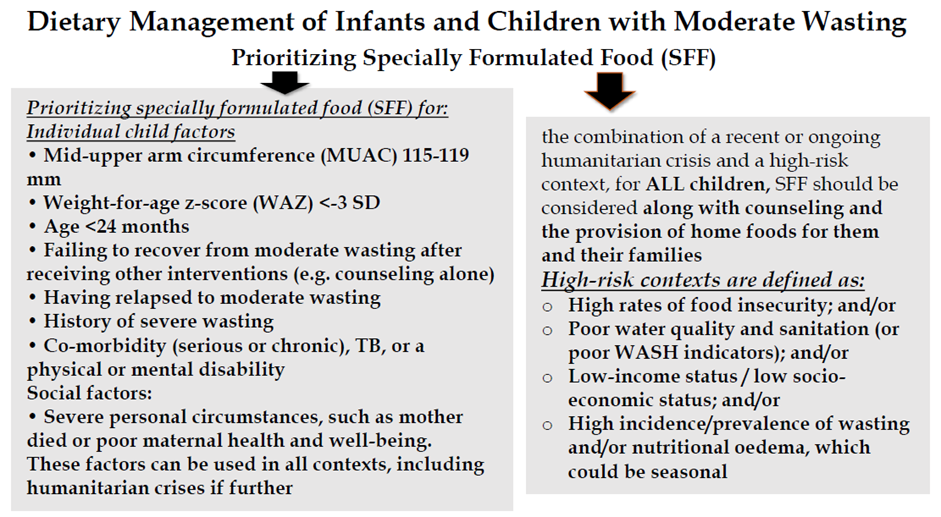

Strong recommendation for, Moderate certainty evidence B17. Prioritizing specially formulated food (SFF) interventions with counseling, compared to counselling alone, should be considered for.

Individual child factors: •mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) 115-119mm •weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) <-3 SD •age <24 months •failing to recover from moderate wasting after receiving other interventions (e.g. Counselling alone) •having relapsed to moderate wasting •history of severe wasting •co-morbidity (medical problems needing mid or long-term follow-up care and with a significant association with nutritional status such as HIV and tuberculosis or a physical or mental disability) Social factors: •Severe personal circumstances, such as mother died or poor maternal health and well-being |

|

B18 |

In infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting I high risk context what they should be considered for? |

WHO 2023 |

Strong recommendation for, Moderate certainty evidence B18. In high-risk contexts (where there is a recent or ongoing humanitarian crisis), all infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting should be considered for specially formulated foods (SFFs) along with counseling and the provision of home foods for them and their families. |

|

B19 |

In infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting who need supplementation with specially formulated foods (SFFs) what is the alternative if it is not available? |

WHO 2023 |

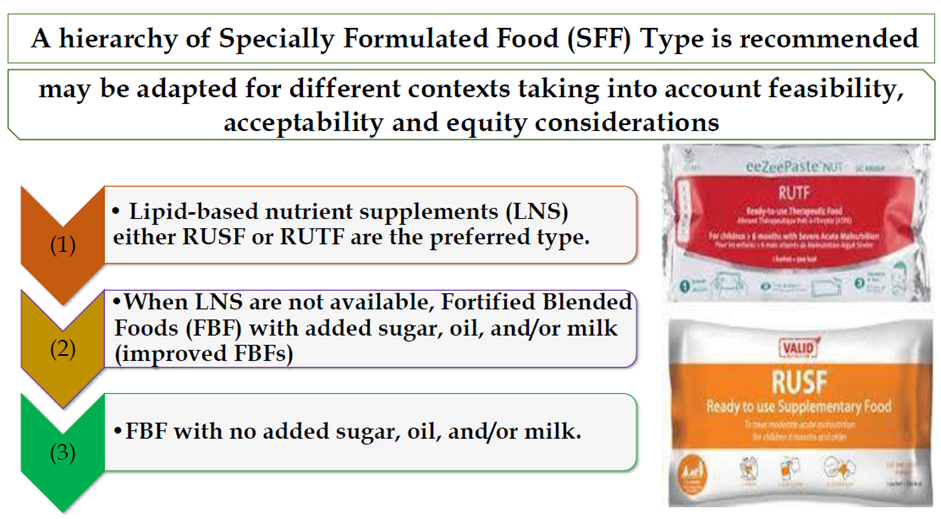

Conditional recommendation for, Low certainty evidence B19. In infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting who need supplementation with specially formulated foods (SFFs), lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS) are the preferred type. When these are not available, Fortified Blended Foods with added sugar, oil, and/or milk (improved FBFs) are preferred compared to Fortified Blended Foods with no added sugar, oil, and/or milk. |

|

B20 |

Infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting who require specially formulated foods (SFFs) how to calculate the required amount? |

WHO 2023 |

Conditional recommendation for, very low certainty evidence B20. Infants and children 6-59 months of age with moderate wasting who require specially formulated foods (SFFs) should be given SFFs to provide 40-60% of the total daily energy requirements needed to achieve anthropometric recovery. Total daily energy requirements needed to achieve anthropometric recovery are estimated to be around 100-130 kcal/kg/day. |

|

B21 |

Vitamin A supplementation in the treatment of children with severe acute malnutrition What is the effectiveness and safety of giving vitamin A supplementation to children with severe acute malnutrition when they are receiving a WHO-recommended therapeutic diet containing vitamin A? |

WHO 2013 |

Strong recommendation for , Low certainty evidence B21. Children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should receive the daily recommended nutrient intake of vitamin A throughout the treatment period. Children with severe wasting and/or nutritional edema should be provided with about 5000 IU vitamin A daily, either as an integral part of therapeutic foods or as part of a multi-micronutrient formulation.*** |

Remarks of recommendations

* In depth assessment and clinical judgment of qualified physicians

** In infants and children aged 2 months up to 5 years [14]

Severe dehydration when two of the following signs:

· Lethargic or unconscious

· Sunken eyes

· Not able to drink or drinking poorly.

· Skin pinch goes back very slowly.

Some dehydration when two of the following signs:

· Restless, irritable

· Sunken eyes

· Drinks eagerly, thirsty

· Skin pinch goes back slowly.

*** Ask about history of vitamin A supplement with current vaccination schedule

|

Table 5. Recommendations |

|||

|

C. post-exit interventions after recovery from wasting and/or nutritional edema |

|||

|

N |

Health questions |

Source Guideline |

Recommendations (Quality of evidence, Strength of Recommendation) |

|

C1 |

Which infants and children at risk of poor growth and development or with moderate or severe wasting or edema require post-exit interventions? If yes, which post-exit interventions are effective? |

GDG |

Good practice statement C1. Mothers/caregivers after their infants and children exit from nutritional treatment should be provided with continuous counseling and education and should be kept in contact with one of presidential initiatives, civil society organizations and Ministry of Social Solidarity for social and financial support to improve overall child health and prevent relapse to wasting. |

|

C2 |

In infants and children at risk of poor growth and development or with wasting and/or nutritional edema what is the role of psychosocial stimulation? |

WHO 2023 |

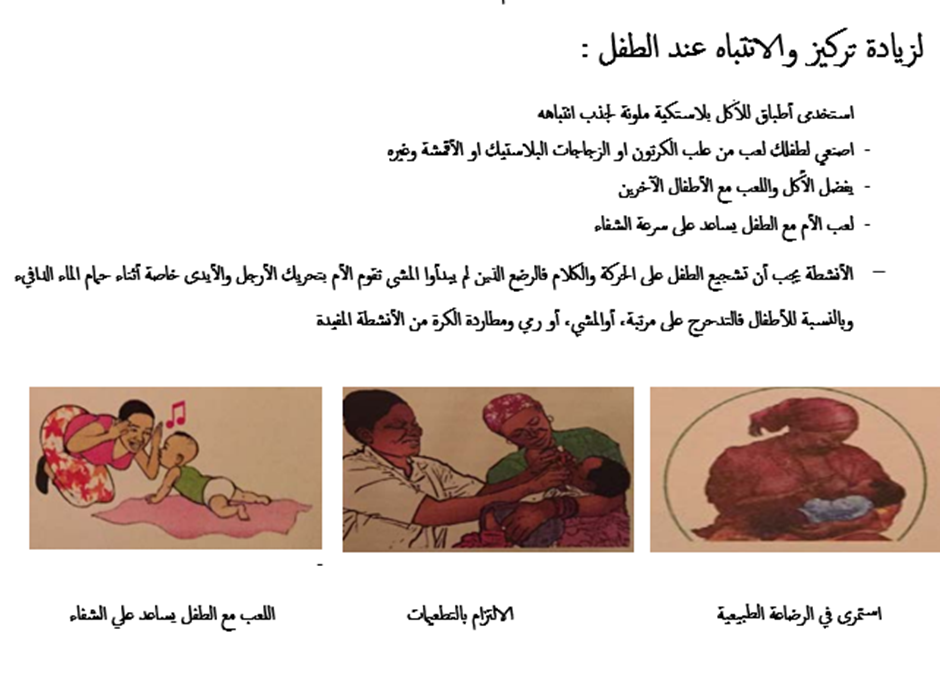

Conditional recommendation for, Low certainty evidence C2. In infants and children at risk of poor growth and development or with wasting and/or nutritional edema, psychosocial stimulation should continue to be provided by mothers/caregivers after transfer from inpatient treatment and exit from outpatient treatment, with psychosocial stimulation interventions * as part of routine care to improve child development and anthropometric outcomes.

|

*Mother /caregiver should be involved in structured play therapy for 15-30 minutes per day with home-made toys. The activities recommended to be related to physical and emotional stimulation, language skills and motor development (as talking, smiling, pointing, enabling, and demonstrating, with or without objects. This also includes responsive feeding as a part of responsive caregiving).

Continuous emotional and physical stimulation that start during rehabilitation and continue after discharge can substantially reduce the risk of permanent mental retardation and emotional impairment.

|

Table 6. Recommendations |

|||

|

D. Prevention of wasting and nutritional edema |

|||

|

N |

Health questions |

Source Guideline |

Recommendations (Quality of evidence, Strength of Recommendation) |

|

D1 |

In communities with infants and children up to five years old at risk of wasting, what community characteristics increase or mitigate risk of wasting for individual children?

|

WHO 2023 |

Good practice statement D1. In contexts where wasting and nutritional edema occur, preventive interventions should ideally be implemented through a multisectoral and multisystem approach (i.e. food, health, safe water, sanitation and hygiene, and social protection systems). These interventions should include access to healthy diets and nutrition and medical services as appropriate, counselling (breastfeeding, health and nutrition related, especially helping families use locally available nutrient-dense foods for a healthy diet), should address maternal and family needs, and should involve psychosocial elements of care to ensure healthy growth and development. |

|

D2 |

In communities with infants and children up to five years at risk of wasting, what is effective community prevention interventions for prevention of wasting?

|

GDG |

Good practice statement D2. Infant and young child feeding counselling must be provided by comprehensively trained health professionals as part of routine care. |

|

D3 |

In communities with infants and children up to five years at risk of wasting, what is the effectiveness of population-based interventions compared to targeted interventions for primary and secondary prevention of wasting? |

WHO 2023 |

Conditional recommendation for, Low certainty evidence D3. a) In areas of or during periods of high food insecurity, in addition to infant and young child feeding counselling, specially formulated foods (SFFs), including medium-quantity lipid-based nutrient supplements (MQ-LNS) or small-quantity lipid-based nutrient supplements (SQ-LNS), may be considered for the prevention of wasting and nutritional edema for a limited duration for all infants and children 6-23 months of age, while continuing to enable access to adequate home diets for the whole family. b) In areas of or during periods of high food insecurity, children living in the most vulnerable households should be prioritized for SFF interventions through a targeted approach. However, when targeting is not possible, these SFFs may need to be given to all households through a blanket approach for infants and children 6-23 months of age, while continuing to enable access to adequate home diets for the whole family and providing infant and young child feeding counselling. |

Evidence to recommendations: Considerations

The GDG was guided by the results of the AGREE II appraisals of the eligible CPGs and thoroughly reviewed the recommendations of the original source WHO CPGs in consideration of local contextual factors related to the national Egyptian health system like burden of the disease, equity, acceptability,feasibility, and other relevant factors. The GDG decided through an informal consensus process to adopt most recommendations however, there was a need to change the strength of 2 recommendations (B2 and B3) as they lack feasibility. Also, GDG develops group of good practice statements to improve acceptability and feasibility- Implementation considerations

To improve nutritional care and patient outcome, evidence-based recommendations must not only be developed, but also disseminated and implemented at national and local levels and integrated into clinical practice.

Dissemination involves educating related healthcare providers to improve their awareness, knowledge and understanding of the guideline’s recommendations. It is one part of implementation, which involved translation of evidence-based guidelines into real life practice with improvement of health outcomes for the patients.

Implementation requires an evidence-based strategy involving professional groups and stakeholders and should consider the local cultural and socioeconomic conditions. Cost-effectiveness of implementation programs should be assessed.

Specific steps need to be followed before clinical practice recommendations can be integrated into local clinical practice, particularly in low resource settings.

Steps of implementing wasting diagnosis, treatment, and prevention strategies into the Egyptian health system:

1. Develop a multidisciplinary working group.

2. Assess the status of nutritional care delivery, care gaps and current needs.

3. Select the material to be implemented, agree on the main goals, identify the key recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and prevention and adapt them to the local context or environment.

4. Identify barriers to, and facilitators of implementation.

5. Select an implementation framework and its component strategies.

6. Develop a step-by-step implementation plan:

· Select the target populations and evaluate the outcome.

· Identify the local resources to support the implementation.

· Set timelines.

· Distribute the tasks to the members.

· Evaluate the outcomes.

7. Continuously review the progress and results to determine if the strategy requires modification.

Guideline implementation strategies will focus on the following: -

1. For Practitioners

· Educational meetings: conferences, lectures, workshops, grand rounds, seminars, and symposia.

· Educational materials: printed or electronic information (software).

· Web-based education: computer-based educational activities.

· A trained person meets with providers in their practice setting to provide information with the intention of changing the provider’s practice. The information may include feedback on the performance of the provider(s).

· Reminders: the provision of information verbally, on papers or on a computer screen to prompt a health professional to recall information or to perform or avoid a particular action related to patient care.

· Optimize professional-patient interactions, through mass media campaigns, reminders, and education materials.

· Practice tools: tools designed to facilitate behavioral/practice changes, e.g., flow charts.

2. For Patients and care givers

· Patient education materials (Arabic booklet): Printed/electronic information aimed at the patient/consumer, family, caregivers, etc.

· Reminders: the provision of information verbally, on papers or electronically to remind a patient/consumer to perform a particular health-related behaviors.

· Mass media campaigns.

3. For Nurses

· Educational meetings: lectures, workshops or traineeships, seminars, and symposia.

· Educational materials: printed.

· A trained person meets with nurses in their practice setting to provide information with the intention of changing the provider’s practice.

· Reminders: the provision of information verbally, on paper or on a computer screen to prompt them to recall information or to perform or avoid a particular action related to patient care.

· Practice tools: tools designed to facilitate behavioral/practice changes.

4. For Stakeholders

Plans have been made to contact with all the health sectors in Egypt including all sectors of the Ministry of Health and Population, National Nutrition Institute, University Hospitals, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Defense, Non-Governmental Organizations, Private sector, andall Health Care Facilities.

· Information and communication technology: Electronic decision support, order sets, care maps, electronic health records, office-based personal digital assistants, etc.

· Any summary of clinical provision of health care over a specified period may include recommendations for clinical action. The information is obtained from medical records, databases, or observations by patients. Summary may be targeted at the individual practitioner or the organization.

· Administrative policies and procedures.

· Formularies: Drug safety programs, electronic medication administration records.

5. Other activities to assist the implementation of the adapted guideline’s recommendations include:

· International initiative: Dissemination of the presented adapted CPG internationally via sending the final adapted CPG to the Guidelines International Network (GIN) Adaptation Working Group and contacting the CPG developers.

· Gantt chart has been designedto manage the dissemination and implementation stages for the adapted CPG over an accurate time frame (Appendix).

Evidence to Decision Tables:

QUESTION B3

|

Should Transition from F70 to ready-to-use Therapeutic food over 2-3 days vs. change abruptly be used for infants and children with severe wasting or edema? |

|

|

POPULATION: |

infants and children with severe wasting or edema |

|

INTERVENTION: |

Transition from F70 to ready-to-use Therapeutic food over 2-3 days |

|

COMPARISON: |

change abruptly |

|

MAIN OUTCOMES: |

|

|

SETTING: |

Inpatient settings during rehabilitation phase |

|

PERSPECTIVE: |

|

|

BACKGROUND: |

|

|

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS: |

|

SUMMARY OF JUDGEMENTS

|

|

|

|

JUDGEMENT |

|

|

|

|

|

PROBLEM |

No |

Probably no |

Probably yes |

Yes |

|

Varies |

Don't know |

|

DESIRABLE EFFECTS |

Trivial |

Small |

Moderate |

Large |

|

Varies |

Don't know |

|

UNDESIRABLE EFFECTS |

Trivial |