Otitis Media with Effusion

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Otorhinolaryngology, Audiovestibular & Phoniatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | Otitis Media with Effusion |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 9:48 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 April 2024"

- Committee

Chair

of the Panel:

Usama Abdel Naseer

Scientific Group Members:

Abdalla Anayet, Abdelrahman Eltahaan, Ahmed Mostafa, Alaa Gaafar, Amr Taha, Ashraf Lotfy, Athar Reda Ibrahim, Bahaa Eltoukhy, Haytham Elfarargy, Hazem Dewidar, Ihab Sifin, Loay Elsharkawy, Mai Mohammed Salama, Mina Esmat, Rania Abdou, Reda Sharkawy, Saad Elzayat, Samir Halim

Abbreviations

AOM: Acute otitis media

OME: Otitis media with effusion

Glossary

Acute otitis media (AOM) The rapid onset of signs and symptoms of inflammation of the middle ear.

Chronic OME OME persisting for 3 months from the date of onset (if known) or from the date of diagnosis (if onset is unknown).

Conductive hearing loss: Hearing loss from the abnormal or impaired sound transmission to the inner ear, which is often associated with effusion in the middle ear but can be caused by other middle ear abnormalities, such as tympanic membrane perforation, or ossicle abnormalities

Hearing assessment A means of gathering information about a child’s hearing status, which may include a caregiver report, audiological assessment by an audiologist, or hearing testing by a physician or allied health professional using screening or standard equipment, which may be automated or manual. Does not include the use of noisemakers or other nonstandardized methods.

Middle ear effusion Fluid in the middle ear from any cause. Middle ear effusion is present with both OME and AOM and may persist for weeks or months after the signs and symptoms of AOM resolve.

Otitis media with effusion (OME) The presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of acute ear infection.

Pneumatic otoscopy A method of examining the middle ear by using an otoscope with an attached rubber bulb to change the pressure in the ear canal and see how the eardrum reacts. A normal eardrum moves briskly with applied pressure, but when there is fluid in the middle ear, the movement is minimal or sluggish.

Sensorineural hearing loss Hearing loss that results from abnormal transmission of sound from the sensory cells of the inner ear to the brain.

Tympanogram An objective measure of how easily the tympanic membrane vibrates and at what pressure it does so most easily (pressure admittance function). If the middle ear is filled with fluid (eg, OME), vibration is impaired, and the result is a flat, or nearly flat, tracing; if the middle ear is filled- Executive Summary

This Guideline is concerned with diagnosis and treatment decision of otitis media with effusion. This is targeting a child aged 2 months through 12 years with OME, with or without developmental disabilities or underlying conditions that predispose to OME and its sequelae. This patient characteristics correspond with inclusion criteria in many OME studies. This guideline, however, does not apply to patients <2 months or >12 years of age.

· The clinician should document the presence of middle ear effusion with pneumatic otoscopy when diagnosing OME in a child.

· The clinician should perform pneumatic otoscopy to assess for OME in a child with otalgia, hearing loss, or both.

· The clinician should obtain tympanometry in children with suspected OME for whom the diagnosis is uncertain after performing (or attempting) pneumatic otoscopy.

· The clinician should manage the child with OME who is not at risk with watchful waiting for 3 months from the date of effusion onset (if known) or 3 months from the date of diagnosis (if onset is unknown).

· The clinician may recommend Autoinflation using a balloon more than 3 times a day as a treatment option.

· The clinician should recommend against (catheterization) as it can result in TM perforation and affect the surrounding organs (epistaxis, emphysema, etc.).

· The clinician should recommend against using intranasal or systemic steroids for treating OME.

· The clinician should recommend against using systemic antibiotics for treating OME, and should recommend against using antihistamines, decongestants, or both for treating OME.

· The clinician should document in the medical record counseling of parents of infants with OME who fail a newborn screening regarding the importance of follow-up to ensure that hearing is normal when OME resolves and to exclude an underlying sensorineural hearing loss.

· The clinician should determine if a child with OME is at increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from middle ear effusion because of baseline sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral factors.

· The clinician should evaluate at-risk children for OME at the time of diagnosis of an at-risk condition and at 12 to 18 months of age (if diagnosed as being at risk prior to this time).

· The clinician should not routinely screen children for OME who are not at risk and do not have symptoms that may be attributable to OME, such as hearing difficulties, balance (vestibular) problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, or ear discomfort.

· The clinician should educate children with OME and their families regarding the natural history of OME, need for follow-up, and the possible sequelae.

· The clinician should obtain an age-appropriate hearing test if OME persists for 3 months or longer OR for OME of any duration in an at-risk child.

· The clinician should counsel families of children with bilateral OME and documented hearing loss about the potential impact on speech and language development.

· The clinician should reevaluate, at 3- to 6-month intervals, children with chronic OME until the effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is identified, or structural abnormalities of the eardrum or middle ear are suspected.

· The clinician should recommend tympanostomy tubes when surgery is performed for OME in a child <4 years old; adenoidectomy should not be performed unless a distinct indication exists (nasal obstruction, chronic adenoiditis).

· The clinician should recommend tympanostomy tubes, adenoidectomy, or both when surgery is performed for OME in a child ³4 years old.

· The clinician should not place long-term tubes as initial surgery for children who meet the criteria for tube insertion unless there is a specific reason based on an anticipated need for prolonged middle ear ventilation beyond that of a short-term tube.

· The clinician should not routinely prescribe postoperative antibiotic ear drops after tympanostomy tube placement.

· The clinician should prescribe topical antibiotic ear drops only, without oral antibiotics, for children with uncomplicated acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea.

· The clinician should not encourage routine, prophylactic water precautions (use of earplugs or headbands, avoidance of swimming or water sports) for children with tympanostomy tubes.

· The clinician should document resolution of OME, improved hearing, or improved quality of life when managing a child with OME.

- Introduction

OME is defined as the presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of acute ear infection.The condition is common enough to be called an ‘‘occupational hazard of early childhood’’ because about 90% of children have OME before school age 5, and they develop, on average, 4 episodes of OME every year. Synonyms for OME include ear fluid and serous, secretory, or nonsuppurative otitis media. OME may occur during an upper respiratory infection, spontaneously because of poor eustachian tube function, or as an inflammatory response following AOM, most often between the ages of 6 months and 4 years. In the first year of life, .50% of children will experience OME, increasing to .60% by age 2 years. When children aged 5 to 6 years in primary school are screened for OME, about 1 in 8 are found to have fluid in one or both ears. The prevalence of OME in children with Down syndrome or cleft palate, however, is much higher, ranging from 60% to 85%.

Most episodes of OME resolve spontaneously within 3 months, but about 30% to 40% of children have repeated OME episodes, and 5% to 10% of episodes last year.6 Persistent middle ear fluid from OME results in decreased mobility of the tympanic membrane and serves as a barrier to sound conduction. At least 25% of OME episodes persist for 3 months and may be associated with hearing loss, balance (vestibular) problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, recurrent AOM, or reduced QOL. Less often, OME may cause structural damage to the tympanic membrane that requires surgical intervention.

The high prevalence of OME—along with many issues, including difficulties in diagnosis and assessing its duration, associated conductive hearing loss, the potential impact on child development, and significant practice variations in management makes OME an important condition for up-to-date clinical practice guidelines.

- Purpose

The purpose of this multidisciplinary guideline is to identify quality improvement opportunities in managing OME and to create explicit and actionable recommendations to implement these opportunities in clinical practice.

Specifically, the goals are to improve diagnostic accuracy, identify children who are most susceptible to developmental sequelae from OME , and educate clinicians and patients regarding the favorable natural history of most OME and the lack of clinical benefits for medical therapy (eg, steroids, antihistamines, decongestants). Additional goals relate to OME surveillance, hearing and language evaluation, and management of OME detected by newborn screening.

The target audience

The guideline is intended for all clinicians who are likely to diagnose and manage children with OME, and it applies to any setting in which OME would be identified, monitored, or managed..

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

inclusion/exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

· Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

· Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

· Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later)

· Selecting peer reviewed publications only

· Selecting guidelines written in English language

· Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input

· Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

• Developing organisation/authors

• Date of publication, posting, and release

• Country/language of publication

• Date of posting and/or release

• Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. the panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 50% on the rigour dimension was retained)

- Evidence assessment

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

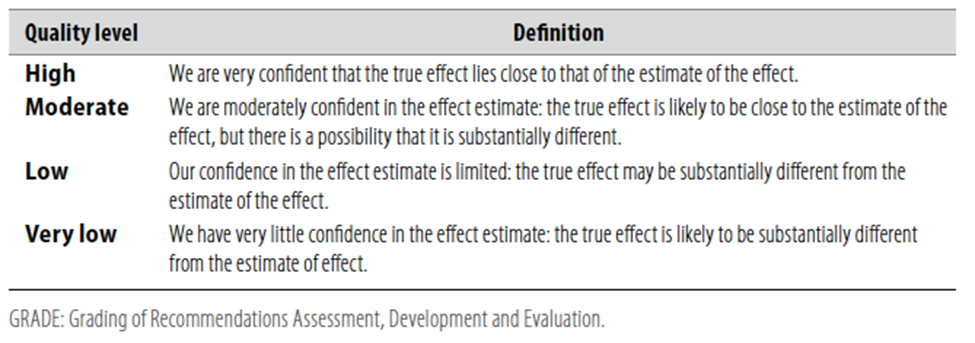

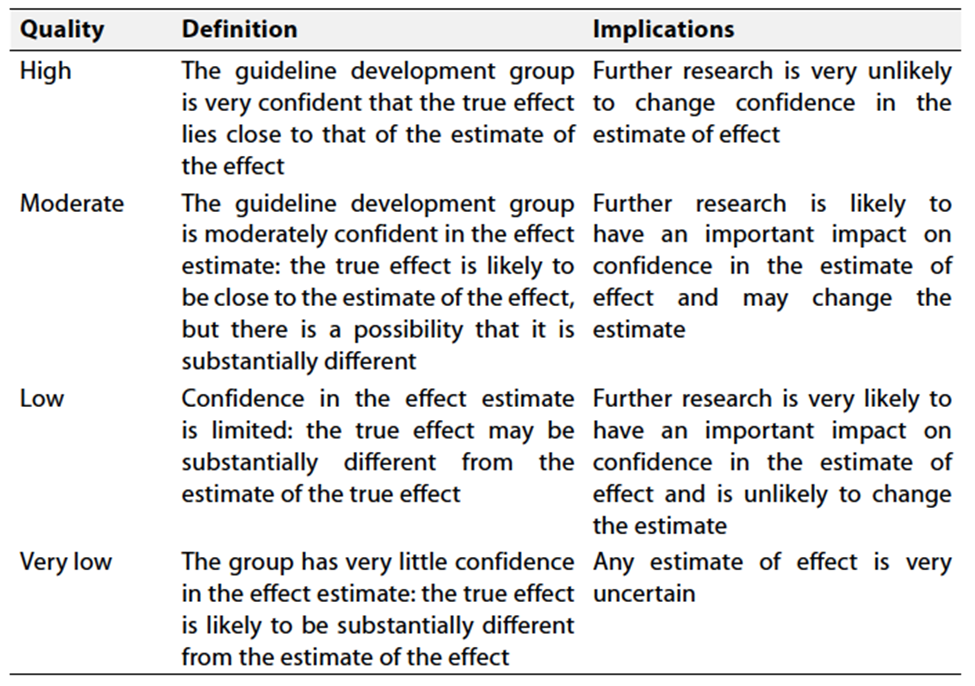

Table 1 Quality of evidence in GRADE

Table 2 Significance of the four levels of evidence

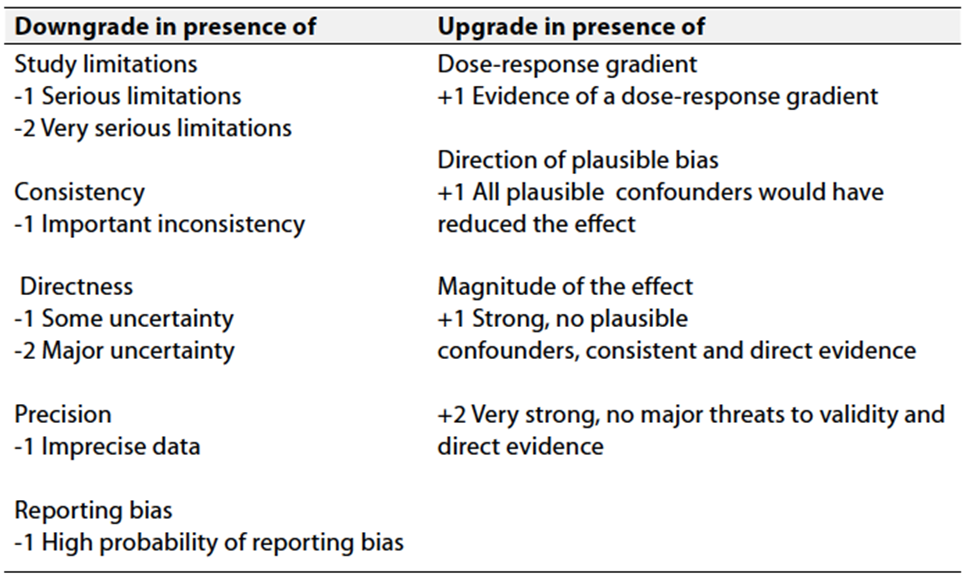

Table 3 Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of evidence

- The strength of the recommendation

The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

Strong recommendations

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

Conditional recommendations

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

When not to make recommendations

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

- Recommendations

1a. Pneumatic otoscopyThe clinician should document the presence of middle ear effusion with pneumatic otoscopy when diagnosing otitis media with effusion (OME) in a child. Strong recommendation High-Quality Evidence (systematic review of cross-sectional studies with a consistent reference standard)3,4 |

|

1b. Pneumatic otoscopy The clinician should perform pneumatic otoscopy to assess for OME in a child with otalgia, hearing loss, or both. Strong recommendation High-Quality Evidence (systematic review of cross-sectional studies with a consistent reference standard)12-14 |

2.TympanometryClinicians should obtain tympanometry in children with suspected OME for whom the diagnosis is uncertain after performing (or attempting) pneumatic otoscopy. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (extrapolation from systematic review of cross-sectional studies with a consistent reference standard for tympanometry as a primary diagnostic method)15-17 |

3. Failed newborn hearing screeningClinicians should document in the medical record counseling of parents of infants with OME who fail a newborn hearing screen regarding the importance of follow-up to ensure that hearing is normal when OME resolves and to exclude an underlying sensorineural hearing loss.18-20 Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (indirect observational evidence on the benefits of longitudinal follow-up for effusions in newborn screening programs and the prevalence of SNHL in newborn screening failures with OME) |

4a. Identifying at-risk childrenClinicians should determine if a child with OME is at increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from middle ear effusion because of baseline sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral factors Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (observational studies regarding the high prevalence of OME in at-risk children and the known impact of hearing loss on child development; expert opinion on the ability of prompt diagnosis to alter outcomes)21-23 |

4b. Evaluating at-risk childrenClinicians should evaluate at-risk children (Table 4) for OME at the time of diagnosis of an at-risk condition and at 12 to 18 mo of age (if diagnosed as being at risk prior to this time). Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (observational studies regarding the high prevalence of OME in at-risk children and the known impact of hearing loss on child development; expert opinion on the ability of prompt diagnosis to alter outcomes)24-26 |

5. Screening healthy childrenClinicians should not routinely screen children for OME who are not at risk (Table 4) and do not have symptoms that may be attributable to OME, such as hearing difficulties, balance (vestibular) problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, or ear discomfort. Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (systematic review of RCTs)27,28 |

6. Patient educationClinicians should educate families of children with OME regarding the natural history of OME, need for follow-up, and the possible sequelae. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (observational studies)29 |

7. Watchful waitingClinicians should manage the child with OME who is not at risk with watchful waiting for 3 mo from the date of effusion onset (if known) or 3 mo from the date of diagnosis (if onset is unknown). Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (systematic review of cohort studies)30 |

8a.AutoinflationClinicians may recommend Autoinflation using a balloon more than 3 times a day as a treatment option. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (systematic review of RCTs)31 |

8b. SteroidsClinicians should recommend against using intranasal steroids or systemic steroids for treating OME. Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (systematic review of well-designed RCTs)32-34 |

8c. AntibioticsClinicians should recommend against using systemic antibiotics for treating OME. Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (systematic review of well-designed RCTs)35 |

8d. Antihistamines or decongestantsClinicians should recommend against using antihistamines, decongestants, or both for treating OME. Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (systematic review of well-designed RCTs)36 |

9. Hearing testClinicians should obtain an age-appropriate hearing test if OME persists for 3 months or for OME of any duration in an at-risk child. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (systematic review of RCTs showing hearing loss in about 50% of children with OME and improved hearing after tympanostomy tube insertion; observational studies showing an impact of hearing loss associated with OME on children’s auditory and language skills)37-40 |

10. Speech and languageClinicians should counsel families of children with bilateral OME and documented hearing loss about the potential impact on speech and language development. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (observational studies; extrapolation of studies regarding the impact of permanent mild hearing loss on child speech and language)41 |

11. Surveillance of chronic OMEClinicians should reevaluate, at 3- to 6-mo intervals, children with chronic OME until the effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is identified, or structural abnormalities of the ear drumor middle ear are suspected. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (observational studies)42-44 |

12a. Surgery for children <4 y oldClinicians should recommend tympanostomy tubes when surgery is performed for OME in a child less than 4 years old; adenoidectomy should not be performed unless a distinct indication (eg, nasal obstruction, chronic adenoiditis) exists other than OME. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (systematic review of RCTs (tubes, adenoidectomy) and observational studies (adenoidectomy)45,46 |

12b. Surgery for children ³4 y oldClinicians should recommend tympanostomy tubes, adenoidectomy, or both when surgery is performed for OME in a child 4 years old or older. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (systematic review of RCTs (tubes, adenoidectomy) and observational studies (adenoidectomy)47-50 |

13. long-term tubesThe clinician should not place long-term tubes as initial surgery for children who meet the criteria for tube insertion unless there is a specific reason based on an anticipated need for prolonged middle ear ventilation beyond that of a short-term tube. Conditional Recommendation (against) Moderate Quality Evidence(based on observational studies)51-53 |

14. Perioperative ear dropsClinicians should not routinely prescribe postoperative antibiotic ear drops after tympanostomy tube placement. Conditional Recommendation (against) Moderate Quality Evidence (Grade B, based on systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and before-and-after studies with a balance between benefit and harm, with a preponderance of benefit over harm)54 |

15. Acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea.Clinicians should prescribe topical antibiotic ear drops only, without oral antibiotics, for children with uncomplicated acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on RCTs demonstrating superior efficacy of topical vs oral antibiotic therapy for otorrhea as well as improvedoutcomes with topical antibiotic therapy when different topical preparations are compared)56-58 |

16. Water precautionsClinicians should not encourage routine, prophylactic water precautions (use of earplugs or headbands, avoidance of swimming or water sports) for children with tympanostomy tubes. Strong Recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (based on systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and multiple observational studies with consistent effects)59,60 |

17. Outcome assessmentWhen managing a child with OME, clinicians should document in the medical record resolution of OME, improved hearing, or improved quality of life. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (randomized trials and before-and-after studies showing resolution, improved hearing, or improved QOL after management of OME)60 |

- Clinical Indicators for Monitoring

1. Documentation of Middle Ear Effusion:

- Indicator: The clinician should document the presence of middle ear effusion using pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry when diagnosing otitis media with effusion (OME) in a child.

2. Timely Initiation of Watchful Waiting:

- Indicator: The clinician should manage children having OME with watchful waiting for 3 months from the date of effusion onset (if known) or 3 months from the date of diagnosis (if onset is unknown), before taking the decision of surgical interference.

3. Follow-up and Counseling:**

- Indicator: The clinician should document counseling of parents of infants with OME who fail newborn screening, emphasizing the importance of follow-up to ensure normal hearing when OME resolves. Additionally, the clinician should educate children with OME and their families about the natural history of OME, the need for follow-up, and possible sequelae.

These indicators cover aspects such as documentation, diagnostic procedures, treatment decisions, and patient education, providing a comprehensive approach to monitoring physician adherence to the clinical guidelines.

Updating the guideline

To keep these recommendations up to date and ensure its validity it will be periodically updated. This will be done whenever a strong new evidence is available and necessitates updation.

Research Needs

1. Assess the usefulness of algorithms combining pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry for detecting OME in clinical practice.

2. Develop prognostic indicators to identify the best candidates for watchful waiting.

3. Evaluate whether there is a causal role of atopy in OME.

- References

1. Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, Hoelting D, Hunter LL, Kummer AW, Payne SC, Poe DS, Veling M, Vila PM, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Feb;154(1 Suppl):S1-S41.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, Grimes AM, Hackell JM, Harrison MF, Haskell H, Haynes DS, Kim TW, Lafreniere DC, LeBlanc K, Mackey WL, Netterville JL, Pipan ME, Raol NP, Schellhase KG. Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol HeadNeck Surg. 2013 Jul;149(1 Suppl):S1-35. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487302. PMID: 23818543.

3. Berkman ND, Wallace IF, Steiner MJ, Harrison M, Greenblatt AM, Lohr KN, Kimple A, Yuen A. Otitis Media With Effusion: Comparative Effectiveness of Treatments [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 May. Report No.: 13-EHC091-EF. PMID: 23762917

4. Rosenfeld RM, Culpepper L, Doyle KJ, Grundfast KM, Hoberman A, Kenna MA, Lieberthal AS, Mahoney M, Wahl RA, Woods CR Jr, Yawn B; American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media with Effusion; American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical practice guideline: Otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004 May;130(5 Suppl):S95-118. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.002. PMID: 15138413.

5. Mandel EM, Doyle WJ, Winther B, Alper CM. The incidence, prevalence and burden of OM in unselected children aged 1-8 years followed by weekly otoscopy through the "common cold" season. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Apr;72(4):491-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.12.008. Epub 2008 Feb 12. PMID: 18272237; PMCID: PMC2292124.

6. Martines F, Bentivegna D, Di Piazza F, Martinciglio G, Sciacca V, Martines E. The point prevalence of otitis media with effusion among primary school children in Western Sicily. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010 May;267(5):709-14. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1131-4. Epub 2009 Oct 27. PMID: 19859723.

7. Flynn T, Möller C, Jönsson R, Lohmander A. The high prevalence of otitis media with effusion in children with cleft lip and palate as compared to children without clefts. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 Oct;73(10):1441-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.07.015. Epub 2009 Aug 25. PMID: 19709760.

8. Williamson IG, Dunleavey J, Bain J, Robinson D. The natural history of otitis media with effusion--a three-year study of the incidence and prevalence of abnormal tympanograms in four South West Hampshire infant and first schools. J Laryngol Otol. 1994 Nov;108(11):930-4. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100128567. PMID: 7829943.

9. Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clin Evid. 2002 Jun;(7):469-76. Update in: Clin Evid. 2002 Dec;(8):511-8. PMID: 12230672.

10. Rosenfeld RM, Kay D. Natural history of untreated otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2003 Oct;113(10):1645-57. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00004. PMID: 14520089.

11. Hidaka H, Ito M, Ikeda R, Kamide Y, Kuroki H, Nakano A, Yoshida H, Takahashi H, Iino Y, Harabuchi Y, Kobayashi H. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of otitis media with effusion (OME) in children in Japan - 2022 update. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022 Dec 26:S0385-8146(22)00232-2.

12. Jones WS, Kaleida PH. How helpful is pneumatic otoscopy in improving diagnostic accuracy? Pediatrics. 2003;112:510-513.

13. Steinbach WJ, Sectish TC. Pediatric resident training in the diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2002;109:404-408.

14. Pichichero ME, Poole MD. Assessing diagnostic accuracy and tympanocentesis skills in the management of otitis media. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1137-1142.

15. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for screening infants and children for outer and middle ear disorders, birth through 18 years. In: Guidelines for Audiologic Screening. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; 1997:15-22.

16. Takata GS, Chan LS, Morphew T, Mangione-Smith R, Morton SC, Shekelle P. Evidence assessment of the accuracy of methods of diagnosing middle ear effusion in children with otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1379-1387.

17. Nozza RJ, Bluestone CD, Kardatzke D, Bachman R. Identification of middle ear effusion by aural acoustic admittance and otoscopy. Ear Hear. 1994;15:310-323.

18. Wittman-Price RA, Rope KA. Universal newborn hearing screening. Am J Nurs. 2002;102:71-77.

19. Calderon R, Naidu S. Further support of the benefits of early identification and intervention with children with hearing loss. Volta Rev. 1999;100:53-84.

20. Kennedy CR, McCann DC, Campbell MJ, et al. Language ability after early detection of permanent childhood hearing impairment. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2131-2141.

21. Ruben RJ. Otitis media: the application of personalized medicine. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:707-712.

22. Ruben RJ, Math R. Serous otitis media associated with sensorineural hearing loss in children. Laryngoscope. 1978;88: 1139-1154.

23. Brookhouser PE, Worthington DW, Kelly WJ. Middle ear disease in young children with sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:371-378.

24. McLaughlin MR. Speech and language delay in children. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:1183-1188.

25. Bess F, Tharpe A. Case history data on unilateral hearing injured children. Ear Hear. 1986;7:14-19.

26. Bess FH, Dodd-Murphy J, Parker RA. Children with minimal sensorineural hearing loss: prevalence, educational performance, and functional status. Ear Hear. 1998;19:339-354.

27. Simpson SA, Thomas CL, van der Linden M, MacMillan H, van der Wouden JC, Butler CC. Identification of children in the first four years of life for early treatment for otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD004163.

28. Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Campbell TF, et al. Effect of early or delayed insertion of tympanostomy tubes for persistent otitis media on developmental outcomes at the age of three years. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1179-1187.

29. Merenstein D, Diener-West M, Krist A, et al. An assessment of the shared-decision model in parents of children with acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1267-1275.

30. Bhutta MF. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of otitis media: construction of a phenotype landscape. Audiol Neurootol. 2014;19:210-223.

31. Simon F, Haggard M, Rosenfeld RM, Jia H, Peer S, Calmels MN, Couloigner V, Teissier N. International consensus (ICON) on management of otitis media with effusion in children. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018 Feb;135(1S):S33-S39.

32. Bhargava R, Chakravarti A. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of topical intranasal mometasone furoate nasal spray in children of adenoidal hypertrophy with otitis media with effusion. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:766 770.

33. Cengel S, Akyol MU. The role of topical nasal steroids in the treatment of children with otitis media with effusion and/or adenoid hypertrophy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006; 70:639-645.

34. Lack G, Caulfield H, Penagos M. The link between otitis media with effusion and allergy: a potential role for intranasal corticosteroids. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:258- 266.

35. van Zon A, van der Heijden GJ, van Dongen TMA, et al. Antibiotics for otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD009163.

36. Griffin G, Flynn CA. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD003423.

37. Brody R, Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Madell R. Parents cannot detect mild hearing loss in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:681-686.

38. Sidell D, Hunter L, Lin L, Arjmand E. Risk factors for hearing loss surrounding pressure equalization tube placement in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150:1048-1055.

39. Harlor AD Jr, Bower C; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report: hearing assessment in infants and children: recommendations beyond neonatal screening. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1252-1263.

40. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Typical speech and language development. http://www.asha.org/ public/speech/development/. Accessed March 24, 2015.

41. Casby MW. Otitis media and language development. Am J Speech Lang Path. 2001;10:65-80.

42. Paradise JL, Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, et al. Developmental outcomes after early or delayed insertion of tympanostomy tubes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:576-586.

43. Rovers MM, Straatman H, Ingels K, et al. The effect of ventilation tubes on language development in infants with otitis media with effusion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2000; 106:E42.

44. Rovers MM, Straatman H, Ingels K, et al. The effect of short-term ventilation tubes versus watchful waiting on hearing in young children with persistent otitis media with effusion: a randomized trial. Ear Hear. 2001;22:191-199.

45. Rovers MM, Black N, Browning GG, Maw R, Zelhuis GA, Haggard MP. Grommets in otitis media with effusion: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2005; 90:480-485.

46. Hellstrom S, Groth A, Jorgensen F. Ventilation tube treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:383-395.

47. Boonacker CWB, Rovers MM, Browning GG, et al. Adenoidectomy with or without grommets for children with otitis media: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess (Winch Eng). 2014;18:1-118.

48. Mikals SJ, Brigger MT. Adenoidectomy as an adjuvant to primary tympanostomy tube placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:95-101.

49. Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Rockette HE, et al. Adenoidectomy for otitis media with effusion in 2-3-year-old children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1718-1724.

50. Hammaren-Malmi S, Saxen H, Tarkkanen J, Mattila PS. Adenoidectomy does not significantly reduce the incidence of otitis media in conjunction with the insertion of tubes in children who are younger than 4 years: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116:185-189.

51. Shaffer AD, Ford MD, Choi SS, Jabbour N. Should children with cleft palate receive early long-term tympanostomy tubes: one institution’s experience. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018; 55(3):389-395.

52. Yang N, Beaudoin PL, Nguyen M, Maille´ H, Maniakas A, Saliba I. Subannular ventilation tubes in the pediatric population: clinical outcomes of over 1000 insertions. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;131:109859.

53. Baik G, Brietzke S. How much does the type of tympanostomy tube matter? A utility-based Markov decision analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(6):1000-1006.

54. Syed MI, Suller S, Browning GG, Akeroyd MA. Interventions for the prevention of postoperative ear discharge after insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(4):CD008512.

55. Russ SA, Kenney MK, Kogan MD. Hearing difficulties in children with special health care needs. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013; 34(7):478-485.

56. Laws G, Hall A. Early hearing loss and language abilities in children with Down syndrome. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(3):333-342.

57. Roland PS, Dohar JE, Lanier BJ, et al. Topical ciprofloxacin/ dexamethasone otic suspension is superior to ofloxacin otic solution in the treatment of granulation tissue in children with acute otitis media with otorrhea through tympanostomy tubes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(6):736-741.

58. Poss JM, Boseley ME, Crawford JV. Pacific Northwest survey: posttympanostomy tube water precautions. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(2):133-135.

59. Ridgeon E, Lawrence R, Daniel M. Water precautions following ventilation tube insertion: what information are patients given? Our experience. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(4):412- 416.

60. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, Balzano A. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049-1054.

- Annexes

Permanent hearing loss independent of otitis media with effusion Suspected or confirmed speech and language delay or disorder Autism spectrum disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders Syndromes (eg, Down) or craniofacial disorders that include cognitive, speech, or language delays Blindness or uncorrectable visual impairment Cleft palate, with or without the associated syndrome Developmental delay |

Table 4: Sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral factors that place children who have otitis media with effusion at increased risk for developmental difficulties (delay or disorder).

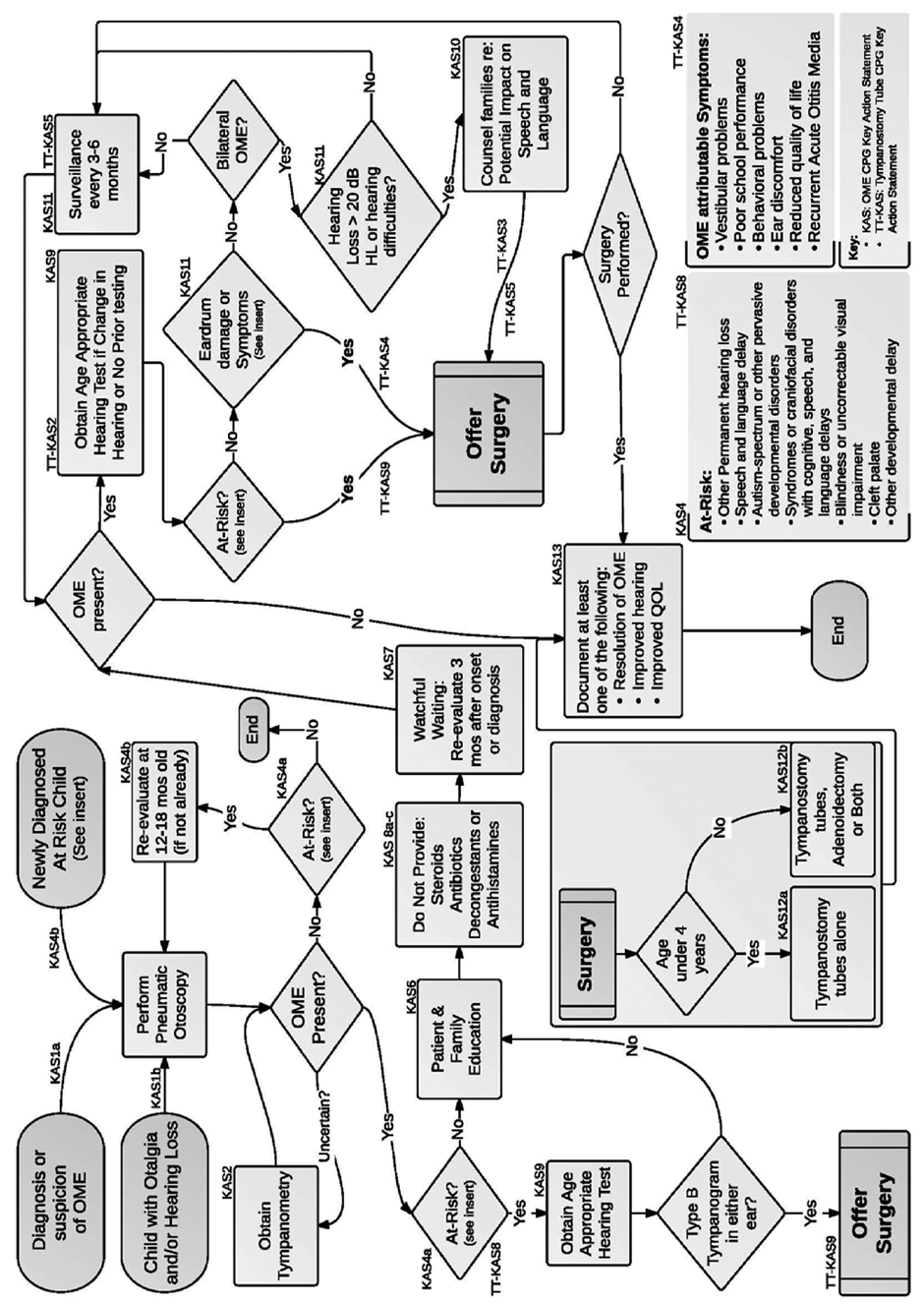

Figure 1: Algorithm showing the relationship of guideline key action statements. OME, otitis media with effusion; QOL, quality of life.