Tonsillectomy in Children

| Site: | EHC | Egyptian Health Council |

| Course: | Otorhinolaryngology, Audiovestibular & Phoniatrics Guidelines |

| Book: | Tonsillectomy in Children |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 9:41 PM |

Description

"last update: 28 April 2024"

- Committee

Chair of the Panel:

Usama Abdel Naseer

Scientific Group Members:

Abdalla Anayet, Abdelrahman Eltahaan, Ahmed Mostafa, Alaa Gaafar, Amr Taha, Ashraf Lotfy, Athar Reda Ibrahim, Bahaa Eltoukhy, Haytham Elfarargy, Hazem Dewidar, Ihab Sifin, Loay Elsharkawy, Mai Mohammed Salama, Mina Esmat, Rania Abdou, Reda Sharkawy, Saad Elzayat,Samir Halim

Abbreviations

ASOT, antistreptolysin O titer

OSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnea

oSDB, obstructive sleep-disordered breathing

PSG, polysomnography

Glossary

Tonsillectomy: It is defined as a surgical procedure performed with or without adenoidectomy that completely removes the tonsil, including its capsule, by dissecting the peritonsillar space between the tonsil capsule and the muscular wall.

Throat infection: is defined as a sore throat caused by viral or bacterial infection of the pharynx, palatine tonsils, or both, which may or may not be culture positive for group A streptococcus. This includes the term strep throat, acute tonsillitis, pharyngitis, adenotonsillitis, or tonsillopharyngitis.

Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (oSDB): is aclinical diagnosis characterized by obstructive abnormalities of the respiratory pattern or the adequacy of oxygenation/ventilation during sleep, which include snoring, mouth breathing, and pauses in breathing. oSDB encompasses a spectrum of obstructive disorders that increases in severity from primary snoring to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Daytime symptoms associated with oSDB may include inattention, poor concentration, hyperactivity, or excessive sleepiness. The term oSDB is used to distinguish oSDB from SDB that includes central apnea and/or abnormalities of ventilation (eg, hypopnea-associated hypoventilation).

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA:) is diagnosed when oSDB is accompanied by an abnormal polysomnography (PSG) with an obstructive apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥1. It is a disorder of breathing during sleep characterized by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and/or intermittent complete obstruction (obstructive apnea) that disrupts normal ventilation during sleep and normal sleep patterns.

The term caregiver is used to refer to parents, guardians, or other adults providing care to children under consideration for or undergoing tonsillectomy- Executive Summary

This guideline predominantly addresses indications for tonsillectomy in children based on obstructive and infectious causes. The evidence that supports tonsillectomy for orthodontic concerns, dysphagia, dysphonia, secondary enuresis, tonsilliths, halitosis, and chronic tonsillitis is limited and generally of lesser quality, and a role for shared decision making is present.

· Clinicians should recommend watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection if there have been<7 episodes in the past year, <5 episodes per year in the past 2 years, or <3 episodes per year in the past 3 years.

· Clinicians should administer a single intraoperative dose of intravenous dexamethasone to children undergoing tonsillectomy.

· Clinicians should recommend ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or both for pain control after tonsillectomy.

· Clinicians should assess the child with recurrent throat infection who does not meet criteria in KAS 2 for modifying factors that may nonetheless favor tonsillectomy, which may include but are not limited to multiple antibiotic allergies/intolerance, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis), or history of >1 peritonsillar abscess.

· Clinicians should not order ASOT. The determination of the antistreptolysin-O titer (ASOT) and other streptococcal antibody titers does not have any value in acute and recurrent tonsillitis / pharyngitis.

· Clinicians should ask caregivers of children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing and tonsillar hypertrophy about comorbid conditions that may improve after tonsillectomy, including growth retardation, poor school performance, enuresis, asthma, and behavioral problems.

· Before performing tonsillectomy, the clinician should refer children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing for polysomnography if they are <2 years of age or if they exhibit any of the following: obesity, Down syndrome, craniofacial abnormalities, neuromuscular disorders, sickle cell disease, or mucopolysaccharidoses.

· The clinician should advocate for polysomnography prior to tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep-disordered breathing in children without any of the comorbidities listed in KAS 5 for whom the need for tonsillectomy is uncertain or when there is discordance between the physical examination and the reported severity of oSDB.

· Clinicians should recommend tonsillectomy for children with obstructive sleep apnea documented by overnight polysomnography.

· Clinicians should counsel patients and caregivers and explain that obstructive sleep-disordered breathing may persist or recur after tonsillectomy and may require further management.

· The clinician should counsel patients and caregivers regarding the importance of managing posttonsillectomy pain as part of the perioperative education process and should reinforce this counseling at the time of surgery with reminders about the need to anticipate, reassess, and adequately treat pain after surgery.

· Clinicians should arrange for overnight, inpatient monitoring of children after tonsillectomy if they are <3 years old or have severe obstructive sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index >10 obstructive events/hour, oxygen saturation nadir <80%, or both).

· Clinicians should follow up with patients and/or caregivers after tonsillectomy and document in the medical record the presence or absence of bleeding within 24 hours of surgery (primary bleeding) and bleeding occurring later than 24 hours after surgery (secondary bleeding).

· The guideline group made a strong recommendation against prescribjng perioperative antibiotics to children undergoing tonsillectomy.

· Clinicians may recommend tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection with a frequency of at least 7 episodes in the past year, at least 5 episodes per year for 2 years, or at least 3 episodes per year for 3 years with documentation in the medical record for each episode of sore throat and 1 of the following: temperature >38.3 C, cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudate, or positive test for group A betahemolytic streptococcus

- Guideline Purpose

The purpose of this guideline is to identify quality improvement

opportunities in managing children undergoing tonsillectomy and to create clear

and actionable recommendations to implement these opportunities in clinical

practice. The target patient population for the guideline is any child 1 to 18

years of age who may be a candidate for tonsillectomy. The guideline does not

apply to populations of children excluded from most tonsillectomy research

studies, including those with neuromuscular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic

cardiopulmonary disease, congenital anomalies of the head and neck region,

coagulopathies, or immunodeficiency.

Target audience

The target audience or intended primary end-users of the guideline are those physicians dealing with patients recommended to have tonsillectomy like Otoaryngologists, pediatricians and family doctors.

- Methods

A comprehensive search for guidelines was undertaken to identify the most relevant guidelines to consider for adaptation.

inclusion/exclusion criteria followed in the search and retrieval of guidelines to be adapted:

· Selecting only evidence-based guidelines (guideline must include a report on systematic literature searches and explicit links between individual recommendations and their supporting evidence)

· Selecting only national and/or international guidelines

· Specific range of dates for publication (using Guidelines published or updated 2015 and later)

· Selecting peer reviewed publications only

· Selecting guidelines written in English language

· Excluding guidelines written by a single author not on behalf of an organization in order to be valid and comprehensive, a guideline ideally requires multidisciplinary input

· Excluding guidelines published without references as the panel needs to know whether a thorough literature review was conducted and whether current evidence was used in the preparation of the recommendations

The following characteristics of the retrieved guidelines were summarized in a table:

• Developing organisation/authors

• Date of publication, posting, and release

• Country/language of publication

• Date of posting and/or release

• Dates of the search used by the source guideline developers

All retrieved Guidelines were screened and appraised using AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) by at least two members. the panel decided a cut-off point or rank the guidelines (any guideline scoring above 50% on the rigour dimension was retained)

- Evidence assessment

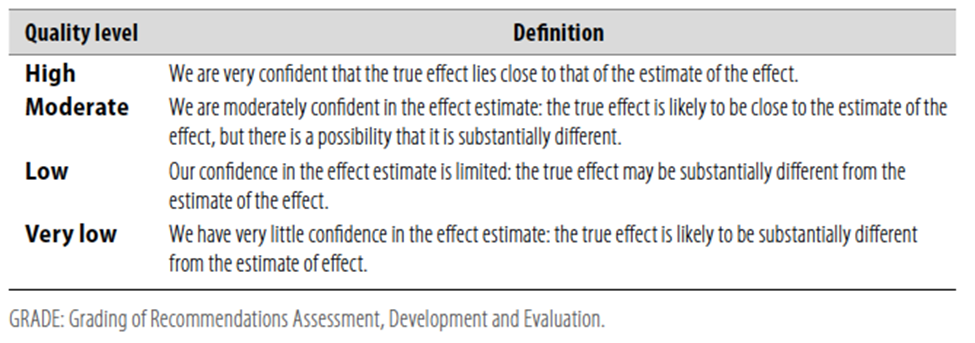

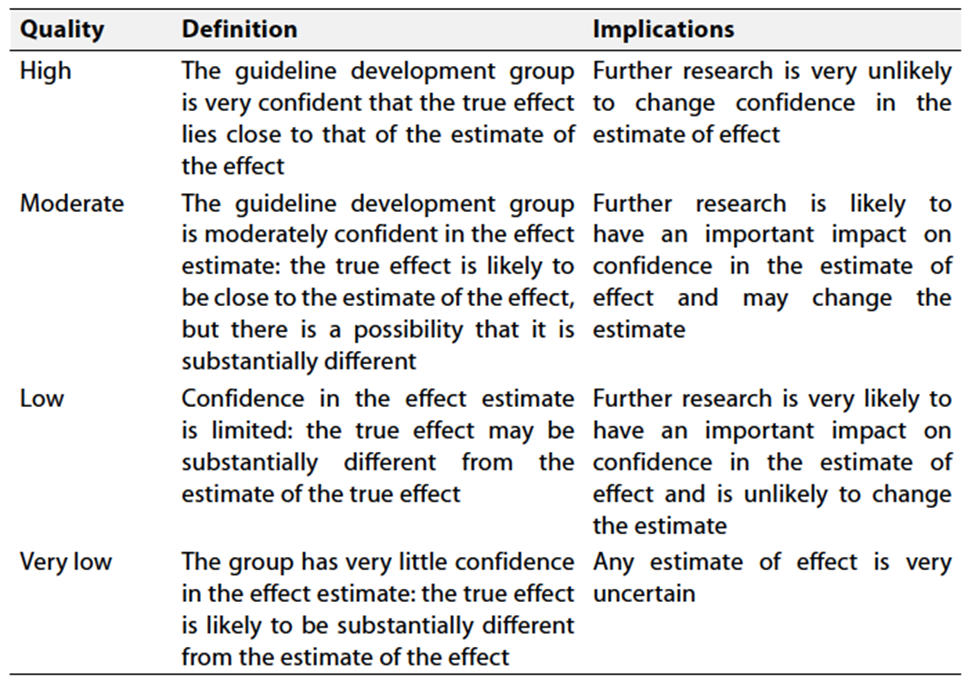

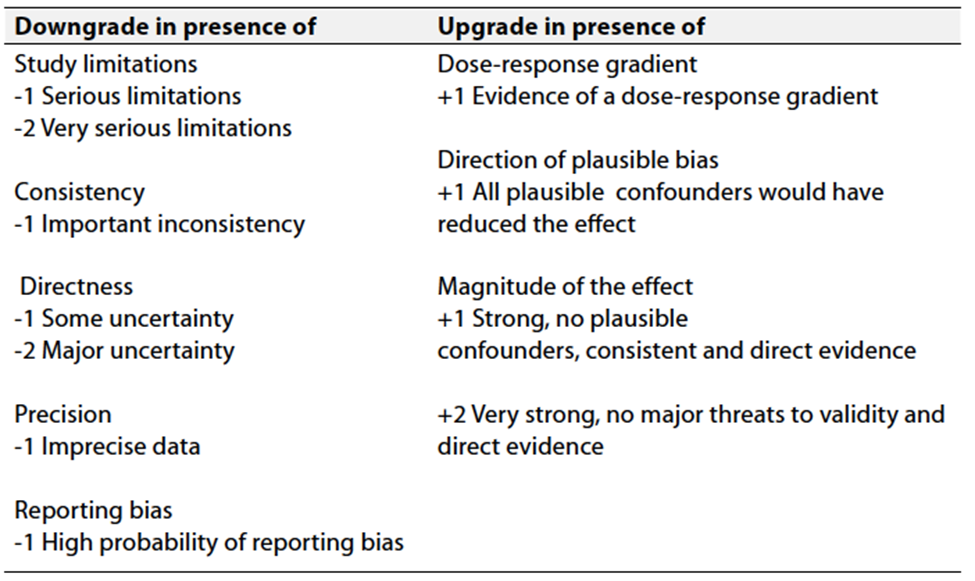

According to WHO handbook for Guidelines we used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of a body of evidence, develop and report recommendations. GRADE methods are used by WHO because these represent internationally agreed standards for making transparent recommendations. Detailed information on GRADE is available on the following sites:

■ GRADE working group: http://www.gradeworkingroup.org

■ GRADE online training modules: http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/

■ GRADE profile software: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro

Table 1 Quality of evidence in GRADE

Table 2 Significance

of the four levels of evidence

Table 3 Factors that determine How to upgrade or downgrade the quality of evidence

- The strength of the recommendation

The strength of a recommendation communicates the importance of adherence to the recommendation.

Strong recommendations

With strong recommendations, the guideline communicates the message that the desirable effects of adherence to the recommendation outweigh the undesirable effects. This means that in most situations the recommendation can be adopted as policy.

Conditional recommendations

These are made when there is greater uncertainty about the four factors above or if local adaptation has to account for a greater variety in values and preferences, or when resource use makes the intervention suitable for some, but not for other locations. This means that there is a need for substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before this recommendation can be adopted as policy.

When not to make recommendations

When there is lack of evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention, it may be appropriate not to make a recommendation.

- Recommendations

1. Watchful waiting for recurrent throat infectionClinicians should recommend watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection if there have been <7 episodes in the past year, <5 episodes per year in the past 2 years, or <3 episodes per year in the past 3 years. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials that fail to show clinically important advantages of surgery over observation alone (as stated in Statement 1)5; Grade C, observational studies showing improvement with watchful waiting)6,7 |

2. Recurrent throat infection with documentationClinicians may recommend tonsillectomy for recurrent throat infection with a frequency of at least 7 episodes in the past year, at least 5 episodes per year for 2 years, or at least 3 episodes per year for 3 years with documentation in the medical record for each episode of sore throat and ≥1 of the following: temperature >38.3 C , cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudate, or positive test for group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus. Conditional Recommendation Moderate Quality Evidence (systematic review of randomized controlled trials with limitations in the consistency with the randomization process regarding recruitment and follow-up; some observational studies)8,9 |

3a. Tonsillectomy for recurrent infection with modifying factorsClinicians should assess the child with recurrent throat infection who does not meet criteria in Key Action Statement 2 for modifying factors that may nonetheless favor tonsillectomy, which may include but are not limited to: multiple antibiotic allergies/intolerance, PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis), or history of >1 peritonsillar abscess. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (systematic review of randomized controlled trials with limitations for PFAPA; observational studies for all other factors)10-16 |

3b. Role of ASOT in decision makingClinicians should not order ASOT. The determination of the antistreptolysin-O titer (ASOT) and other streptococcal antibody titers does not have any value in acute and recurrent tonsillitis / pharyngitis, Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trials)17 |

4. Tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep-disordered breathingClinicians should ask caregivers of children with obstructive sleepdisordered breathing (oSDB) and tonsillar hypertrophy about comorbid conditions that may improve after tonsillectomy, including growth retardation, poor school performance, enuresis, asthma, and behavioral problems. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and before-and-after observational studies)18-21 |

5. Indications for polysomnographyBefore performing tonsillectomy, the clinician should refer children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (oSDB) for polysomnography (PSG) if they are <2 years of age or if they exhibit any of the following: obesity, Down syndrome, craniofacial abnormalities, neuromuscular disorders, sickle cell disease, or mucopolysaccharidoses. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (observational studies with consistently applied reference standard; and one systematic review of observational studies on obesity)22-25 |

6. Additional recommendations for polysomnographyThe clinician should advocate for polysomnography (PSG) prior to tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (oSDB) in children without any of the comorbidities listed in Key Action Statement 5 for whom the need for tonsillectomy is uncertain or when there is discordance between the physical examination and the reported severity of oSDB. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (a randomized controlled trial, observational and case-control studies)26,27 |

7. Tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apneaClinicians should recommend tonsillectomy for children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) documented by overnight polysomnography (PSG). Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trial, observational before-and-after studies, and meta-analysis of observational studies showing substantial reduction in the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing and abnormal PSG after tonsillectomy)28-29 |

8. Education regarding persistent or recurrent obstructive sleep-disordered breathingClinicians should counsel patients and caregivers and explain that obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (oSDB) may persist or recur after tonsillectomy and may require further management. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trial, systematic reviews, and before-andafter observational studies)30 |

9. Perioperative pain counselingThe clinician should counsel patients and caregivers regarding the importance of managing posttonsillectomy pain as part of the perioperative education process and should reinforce this counseling at the time of surgery with reminders about the need to anticipate, reassess, and adequately treat pain after surgery. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trials and observational studies)31-34 |

10. Perioperative antibioticsClinicians should not administer or prescribe perioperative antibiotics to children undergoing tonsillectomy Strong recommendation (against) High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, showing no benefit in using perioperative antibiotics to reduce posttonsillectomy morbidity)35-37 |

11. Intraoperative steroidsClinicians should administer a single intraoperative dose of intravenous dexamethasone to children undergoing tonsillectomy Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (randomized controlled trials and multiple systematic reviews, for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV); randomized controlled trials and systematic review for decreased pain and shorter times to oral intake)38,39 |

12. Inpatient monitoring for children after tonsillectomyClinicians should arrange for overnight, inpatient monitoring of children after tonsillectomy if they are < 3 years old or have severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA; apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] ≥10 obstructive events/hour, oxygen saturation nadir <80%, or both). Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (observational studies on age, meta-analysis of observational studies regarding complications)40-42 |

13. Postoperative ibuprofen and acetaminophenClinicians should recommend ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or both for pain control after tonsillectomy. Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on systematic review and randomized controlled trials)43,44 |

14. Outcome assessment for bleedingClinicians should follow up with patients and/or caregivers after tonsillectomy and document in the medical record the presence or absence of bleeding within 24 hours of surgery (primary bleeding) and bleeding occurring later than 24 hours after surgery (secondary bleeding). Strong recommendation High Quality Evidence (based on observational studies with a preponderance of benefit over harm.)45,46

|

- Clinical Indicators for Monitoring

1. Frequency-based Assessment:

Ensure that clinicians recommend watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection based on the specified frequency criteria: <7 episodes in the past year, <5 episodes per year in the past 2 years, or <3 episodes per year in the past 3 years.

2. Intraoperative Dexamethasone Administration:

Monitor if clinicians administer a single intraoperative dose of intravenous dexamethasone to children undergoing tonsillectomy.

3. Pain Control Recommendations:

Verify that clinicians recommend ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or a combination of both for pain control after tonsillectomy.

4. Avoidance of ASOT Testing:

Confirm that clinicians refrain from ordering the antistreptolysin-O titer (ASOT) for acute and recurrent tonsillitis/pharyngitis, as it is deemed not valuable.

5. Comorbidity Assessment for Sleep-disordered Breathing:

Ensure that clinicians inquire about comorbid conditions related to obstructive sleep-disordered breathing in children with tonsillar hypertrophy, including growth retardation, poor school performance, enuresis, asthma, and behavioral problems.

6. Polysomnography Referral and Advocacy:

Monitor whether clinicians appropriately refer children for polysomnography before tonsillectomy based on age or the presence of specific comorbidities, and advocate for polysomnography when the need for tonsillectomy is uncertain or when there is discordance between examination and reported severity.

These indicators cover a range of key recommendations from the guidelines, ensuring proper adherence and patient care.

Updating the guideline

To keep these recommendations up to date and ensure its validity it will be periodically updated. This will be done whenever a strong new evidence is available and necessitates updation.

Research Needs

1.Investigate the treatment of recurrent throat infections by tonsillectomy versus antibiotics/watchful waiting (<12 and >12 months) using a multicenter randomized controlled trial design.

2. Assess the immunologic role of the tonsils and, specifically, at what point the benefits of tonsillectomy exceed the harm, using a biomarker approach.

3. Determine the cost-effectiveness (direct and indirect) of different tonsillectomy techniques.

- References

1. Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, Rosenfeld RM, Coles S, Finestone SA, Friedman NR, Giordano T, Hildrew DM, Kim TW, Lloyd RM, Parikh SR, Shulman ST, Walner DL, Walsh SA, Nnacheta LC. Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update)-Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Feb;160(2):187-205. doi: 10.1177/0194599818807917. PMID: 30921525.

2. Windfuhr JP, Toepfner N, Steffen G, Waldfahrer F, Berner R. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillitis I. Diagnostics and nonsurgical management. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Apr;273(4):973-87. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3872-6. Epub 2016 Jan 11. PMID: 26755048; PMCID: PMC7087627.

3. Barrette LX, Harris J, De Ravin E, Balar E, Moreira AG, Rajasekaran K. Clinical practice guidelines for pain management after tonsillectomy: Systematic quality appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 May;156:111091. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2022.111091. Epub 2022 Feb 24. PMID: 35240561.

4. Chaidas K, Winterborn C. Oxford guidelines for adult day-case tonsillectomy. J Perioper Pract. 2023 Jan-Feb;33(1-2):9-14. doi: 10.1177/17504589211031067. Epub 2021 Aug 16. PMID: 34396825.

5. Morad A, Sathe NA, Francis D, et al. Tonsillectomy versus watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163490.

6. Burton MJ, Galsziou PP, Chong LY, Venekamp RP. Tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy versus non-surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD001802.

7. Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. History of recurrent sore throat as an indication for tonsillectomy: predictive limitations of histories that are undocumented. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:409-413.

8. van Staaij BK, van den Akker EH, Rovers MM, et al. Effectiveness of adenotonsillectomy in children with mild symptoms of throat infections or adenotonsillar hypertrophy: open, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329:651.

9. Burton MJ, Glasziou PP. Tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy versus non-surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1): CD001802.

10. Feder HM, Salazar JC. A clinical review of 105 patients with PFAPA (a periodic fever syndrome). Acta Paediatr. 2010;99: 178-184.

11. Renko M, Salo E, Putto-Laurila A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of tonsillectomy in periodic fever, apthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2007;151:289-292.

12. Garavello W, Romagnoli M, Gaini RM. Effectiveness of adenotonsillectomy in PFAPA syndrome: a randomized study. J Pediatr. 2009;155:250-253.

13. Burton MJ, Pollard AJ, Ramsden JD, Chong LY, Venekamp RP. Tonsillectomy for periodic fever, apthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis syndrome (PFAPA). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD008669.

14. Johnson RF, Stewart MG. The contemporary approach to diagnosis and management of peritonsillar abscess. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:157-160.

15. Herzon FS, Harris P. Mosher Award thesis. Peritonsillar abscess: incidence, current management practices, and a proposal for treatment guidelines. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(8)(pt 3, suppl 74):1-17.

16. Schraff S, McGinn JD, Derkay CS. Peritonsillar abscess in children: a 10-year review of diagnosis and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57:213-218. Heubi C, Shott SR. PANDAS: pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections an uncommon, but important indication for tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:837-840.

17. Boiko NV, Kim AS, Stagnieva IV, Lodochkina OE, Filonenko NA. Znachenie pokazateleĭ antistreptolizina O pri opredelenii pokazaniĭ k tonzilléktomii u deteĭ [The significance of antistreptolysin O characteristics for the determination of indications for tonsillectomy in the children]. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2018;83(4):73-77. Russian. doi: 10.17116/otorino201883473. PMID: 30113584.

18. Arens R, McDonough JM, Corbin AM, et al. Upper airway size analysis by magnetic resonance imaging of children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:65-70.

19. Arens R, McDonough JM, Costarino AT, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the upper airway structure of children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:698-703.

20. Hultcrantz E, Svanholm H, Ahlqvist-Rastad J. Sleep apnea in children without hypertrophy of the tonsils. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1988;27:350-352.

21. Avior G, Fishman G, Leor A, et al. The effect of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy on inattention and impulsivity as measured by the Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA) in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:367-371.

22. Statham MM, Elluru RG, Buncher R, Kalra M. Adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in young children: prevalence of pulmonary complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:476-480.

23. Weatherly RA, Ruzicka DL, Marriott DJ, Chervin RD. Polysomnography in children scheduled for adenotonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:727-731.

24. Carroll JL, McColley SA, Marcus CL, et al. Inability of clinical history to distinguish primary snoring from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Chest. 1995;108:610-618.

25. Baijal RG, Bidani SA, Minard CG, Watcha MF. Perioperative respiratory complications following awake and deep extubation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25:392-399.

26. Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep. 2006;29:1115-1134.

27. Schwartz J. Societal benefits of reducing lead exposure. Environ Res. 1994;66:105-124. Chervin RD, Ellenberg SS, Hou X, et al. Prognosis for spontaneous resolution of obstructive sleep apnea in children. Chest. 2015;148:1204-1213.

28. Garetz SL, Mitchell RB, Parker PD, et al. Quality of life and obstructive sleep apnea symptoms after pediatric adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e477-e486.

29. Katz ES, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al. Growth after adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134:282-289.

30. Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, et al. Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:676-683.

31. Lauder G, Emmott A. Confronting the challenges of effective pain management in children following tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:1813-1827.

32. Tan GX, Tunkel DE. Control of pain after tonsillectomy in children: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:937-942.

33. Rosales A, Fortier MA, Campos, Kain ZN. Postoperative pain management in Latino families: parent beliefs about analgesics predict analgesic doses provided to children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26:307-314.

34. Rony RY, Fortier MA, Chorney JM, et al. Parental postoperative pain management: attitudes, assessment, and management. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1372-e1378.

35. Dhiwakar M, Clement WA, Supriya M, McKerrow W. Antibiotics to reduce post-tonsillectomy morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD005607.

36. Al-Layla A, Mahafza TM. Antibiotics do not reduce posttonsillectomy morbidity in children. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:367-370.

37. Edmund A, Milder EA, Rizzi MD, et al. Impact of a new practice guideline on antibiotic use with pediatric tonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:410-416.

38. Steward DL, Grisel J, Meinzen-Derr J. Steroids for improving recovery following tonsillectomy in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD003997.

39. Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, Lorenzetti BB, et al. Role of lipocortin-1 in the anti-hyperalgesic actions of dexamethasone. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:883-888.

40. Thongyam A, Marcus CL, Lockman JL, et al. Predictors of perioperative complications in higher risk children after adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:1046-1054.

41. Amoils M. Postoperative complications in pediatric tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in ambulatory vs inpatient setting. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:344-350.

42. Keamy DG, Chhabra KR, Hartnick CJ, et al. Predictors of complications following adenotonsillectomy in children with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:1838-1841.

43. Moss JR, Watcha MF, Bendel LP, McCarthy DL, Witham SL, Glover CD. A multicenter, randomized double-blind placebo controlled, single dose trial of the safety and efficacy of intravenous ibuprofen for treatment of pain in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy. Paediatr Anesth. 2014;24: 483-489.

44. Riggin L, Ramakrishna J, Sommer DD, Koren G. A 2013 updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 randomized controlled trials; no apparent effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the risk of bleeding after tonsillectomy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2013;38:115-129.

45. Royal College of Surgeons of England. National prospective tonsillectomy audit: final report of an audit carried out in England and Northern Ireland between July 2003 and September 2004. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/ college-publications/docs/tonsillectomy-audit/. Published May 2005. Accessed August 27, 2017.

46. McClelland L, Jones NS. Tonsillectomy: haemorrhaging ideas. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:753-758

- Annexes

Figure 1. Tonsillectomy in children: clinical

practice guideline algorithm. KAS, key action statement; OSA, obstructive sleep

apnea; PFAPA, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis;

PSG, polysomnography